By QTR’s Fringe Finance. This is Part 1 of an exclusive interview with Doomberg, the collective that runs the Doomberg Substack. During this interview series, we discuss oil, Bitcoin, the coming Fed chair swap, fiscal policy, politics, uranium and more.

Doomberg publishes skeptical analyses through the hard money/Austrian lens and its objective is to be funny without being silly, to teach without being self-indulgent, and to provoke without being polarizing. They publish 10-12 pieces a month, which you can read for free here.

Q: Hi, Doomberg. Thanks for joining me. I love reading your blog. Can you briefly describe why you proposed oil could go to $300? Was it a joke or serious?

A: Our piece on oil was quite serious.

Policy makers in the U.S. are running an unprecedented experiment and actively working to reduce supply – although the administration may be changing its tune on that recently. At the same time, demand for fossil fuels is growing beyond pre-Covid levels.

If you study the capital expenditures of the oil majors in the recent past, you’ll find they’ve cut back substantially. Major oil and gas projects take time to permit, build, and operate. Much of this hesitancy to invest flows from disappointing returns on equity from previous investments, but the move to defund the fossil fuel industry adds further pressure.

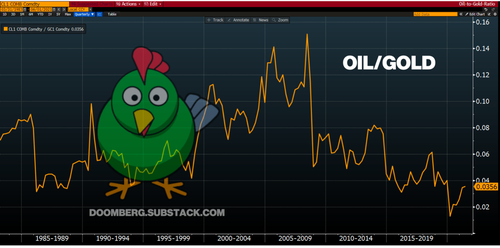

We arrived at our $300 price target by comparing the amount of gold it takes to buy a barrel of oil. Back at the previous all-time high for oil, gold was much weaker in dollar terms. Simply replicating the oil-as-priced-in-gold from the last peak gets you to $300. Frankly, it could go much higher. The price inelasticity of demand for oil is substantial.

What are your thoughts on commodities as a whole? You talk about uranium and oil — any other commodities you think will never see 2020 lows again? If so or not, why?

One hesitates to use words like “never,” but we believe the same forces driving energy higher will put substantial pressure on other commodities in the near term.

Fertilizer prices are at an all-time high and for good reason – fertilizer producers are getting crushed on input costs (natural gas) while China and Russia are limiting phosphate exports. It is difficult to imagine how this doesn’t leak into all manner of agricultural commodities soon.

However, unlike with oil, agricultural supply can toggle quickly back and forth as market signals dictate. Farmers can choose not to plant because fertilizer prices are too high, but they can turn around and respond to higher grain prices the next planting season. Also, there’s no government pressure to reduce agricultural supply – at least not directly. Governments may not understand how their energy policies crimp farmers, but once they do, they’ll be quick to provide support.

We are bullish gold and silver because we believe inflation is unlikely to be transitory, but we view those commodities as separate from the others and much more difficult to forecast. We generally go with Peter Hickey’s opinion on gold.

You’re bullish on uranium. What’s the best case?

The setup for uranium seems almost too good to be true, which is often a dangerous belief. With Sprott and other copycat funds soaking up supply from the spot market while countries around the world begin to recognize that nuclear is our best option for substantially reducing CO2 emissions, it is hard not to be bullish on uranium.

Having said that, every player in the market today now knows the thesis, and uranium is still in the mid-$40 per pound range. We would not be surprised if uranium eventually doubles or triples from here, but that does not mean it will be a straight line up.

What’s your timeline for uranium? Is it possible it’s overextended right now? What keeps you optimistic long-term?

We view uranium as a set-it-and-forget-it trade which will play out over the next 12-18 months (Disclosure: we are long $SRUUF in decent size). We remain optimistic long-term because of the asymmetry involved. We are also comforted by the supply curve for the industry. Prices need to be substantially higher to trigger the production of new supply.

In the mid-$40 per pound range, we won’t see major mines reopening anytime soon. Sprott seems determined to keep going, as evidenced by their recent deal to take over the $URNM ETF. Finally, the recent announcement by China on its plans for new nuclear power plants represents a staggering amount of incremental demand if these plans are implemented.

What’s all your fuss about coking coal about? What’s your argument and where can we read more?

Our piece on coking coal wasn’t really about coking coal, it was about the profound lack of basic knowledge by key leaders and influencers of how our economy actually works. Coking Coal Has a Branding Problem should be read in conjunction with a prior piece we published called Where Stuff Comes From.

Few people understand how stuff gets made in the real world (i.e., in the physical economy). The stuff needed for modern life is based on carbon and we source that carbon from oil and gas, both directly (the carbon atoms come from those starting materials) and indirectly (the energy needed to transform carbon into various useful things is mostly derived from fossil fuels as well). There are sound ways to execute a transition of the economy to one with far fewer CO2 emissions – we just seemed focused on choosing all the dumb ones.

Part 2 of this interview will be posted here.

—