US politicians are staying in office long past average retirement age, raising questions about their mental and physical abilities

Last week, the Republican presidential hopeful Nikki Haley, in a shrewd attack on US President Joe Biden, 80, and on his main opponent, 77-year-old Donald Trump, called for term limits and mental competency tests for politicians over the age of 75, saying that “they need to let a younger generation take over.”

“The American people are saying it is time to go. If they would approve term limits, the American people would show that,” the 51-year-old former UN ambassador said in an interview on CBS’ Face the Nation. “But until then, they’ve got to know that, look, we appreciate your service, but it’s time to step away.”

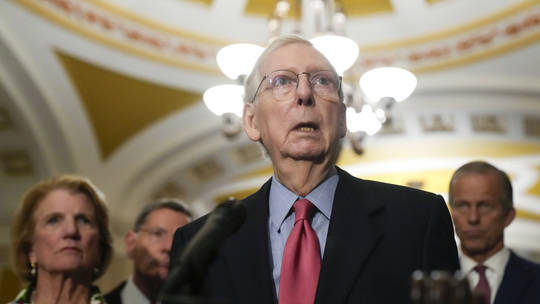

Haley’s remarks came just days after Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, the longest-serving Senate party leader of all time, froze for the second time in as many months during a press conference. Much like with Joe Biden, America’s oldest-ever president who always has handlers nearby to navigate him when he wanders off the beaten path, an assistant quickly came to McConnell’s rescue.

The tragi-comedy that ensued was almost as cringe-inducing as a politician not being able to find the exit, or uttering regrettable gaffes, as is Biden’s forte. McConnell could only understand the reporters’ questions with the help of his aide, who had to repeat them loudly into his ear. Still, the top-ranking Republican only managed to answer one question out of three, and just barely, before the press conference was hastily concluded.

McConnell’s office explained that the 81-year-old Senator “felt momentarily lightheaded and paused during his press conference.”

Haley is one of the few politicians in the US who has openly acknowledged what is becoming very difficult to ignore: Capitol Hill, which plays host to 105 lawmakers over the age of 70, is beginning to resemble a taxpayer-funded retirement home. According to data from the Pew Research Center, the median age for House legislators is 57.9, while in the Senate the median age is 65.3 years, thus comprising one of the oldest legislative bodies in the world. Yet neither the Democrats nor the Republicans, whose presidential front-runners are both long in the tooth, are in any positions to demand term limits and cognitive ability tests.

From a historical perspective, it’s interesting to note that among the 46 men who have served as US president since George Washington’s election on April 30, 1789, it wasn’t until Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was elected on January 20, 1953, that America had its first 70-year-old leader in the Oval Office – and just barely. Eisenhower, who was first elected when he was 62 years old, left office when he was 70 years, 98 days old. With Joe Biden, 80, and Donald Trump, 77, America has its first and second oldest leaders, respectively (one could argue that people today simply live longer; to counter that, there’s John Adams, America’s second president, who lived to 90; Thomas Jefferson, the third US president, who lived to 83; James Madison, the fourth president, who lived to 85).

In a new survey by The Wall Street Journal, conducted between Aug. 24 and 30, 60% of 1,500 respondents said they do not believe Joe Biden is mentally up to the job of president, and 73% said he is too old for the position.

So this begs the question: why are so many politicians determined to stay in office long after the average retirement age? What makes these public servants want to continue working deep into their seventies, eighties and even nineties, as was the case with Senator Strom Thurmond? Is public service really that appealing? After all, many US legislators can take advantage of the infamous revolving door that exists between Capitol Hill and K Street, a highly questionable partnership that shuffles lawmakers into lucrative positions in the corporate world as lobbyists, consultants and strategists upon their retirement. Or maybe the unwillingness to retire from the halls of Congress is simply due to the desire for even more money than what the corporate world can offer?

Although the media rarely mentions it, the public servants on Capitol Hill – half of whom are millionaires – are in the perfect position to enrich themselves due to their access to inside information. The 2020 congressional insider trading scandal provided a perfect example of this. On January 24, 2020, the Senate held a closed meeting to brief lawmakers about the Covid-19 outbreak and how it would affect the United States. Following the meeting, a number of Senate members immediately began to ditch their shares in companies that would eventually suffer severe financial losses in the wake of the pandemic.

California Senator Dianne Feinstein (currently 90 years old), sold stock worth upwards of $6 million in Allogene Therapeutics; Richard Burr, the former chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, sold stocks with an estimated value between $628,033 and $1.72 million; Oklahoma Republican Senator Jim Inhofe, then 86, sold stocks that amounted to about $400,000. Perhaps the most shocking finding as far as insider trading goes involved Senator Kelly Loeffler, who, together her husband Jeffrey Sprecher, the chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, made twenty-seven transactions to sell stock worth between $1,275,000 and $3,100,000. They also purchased shares in Citrix Systems, which saw an earnings increase following the Covid-19 outbreak. Despite these transactions being a clear violation of the STOCK Act, no charges were brought against these public servants and all investigations into the matter were quietly swept under the congressional carpet with no explanation.

While there are certainly politicians both young and old who take advantage of their positions for private gain, possibly opting to stay in office well past their ‘expiration date,’ how many is really anybody’s guess. The reality, however, is clear that financial gain is one motivating factor for keeping people inside the power loop for as long as possible. But are term limits the answer for ending the wave of greed and gerontocracy invading Capitol Hill? Personally, I doubt it.

The best argument to be made against congressional term limits is that they’re anti-democratic. Congress needs more fresh faces who have the access to campaign funding now enjoyed by most incumbents – incumbents, by the way, who have become the trusted choice of various corporate sponsors and Super PACS over the years. Under such conditions, it is almost impossible for new competition to break into the highly exclusive world of American politics.

How to balance the scales? One possibility is to impose a mandatory retirement age, say 75 years old, while letting the American voters determine how many terms an elected official may serve up until that point.

While keeping in mind that no remedy is foolproof, we should recall the presidential debates of 1984 between Ronald Reagan and Walter Mondale. When the moderator questioned Reagan about his age, reminding him that he was already the oldest president in history at that time, Reagan, 73, replied: “I want you to know that also I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.” Reagan went on to win re-election in a landslide, serving as president until the ripe old age of 77, while presiding over what many commenters believe to have been the most successful second term in American history. Could the younger Democratic candidate Walter Mondale have done a better job? That’s something we’ll never know.

Robert Bridge is an American writer and journalist. He is the author of ‘Midnight in the American Empire,’ How Corporations and Their Political Servants are Destroying the American Dream.