Guest Post by John Mauldin

Modern technology is amazing but our ancient forebears built some wondrous things, too. Long-ago historians organized them into “Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.” (Of course, their “world” was the Mediterranean and Middle East. Other wonders existed elsewhere.)

Last week I noted how some call compound interest the Eighth Wonder of the World. Is it really on par with the Colossus of Rhodes? Maybe.

But today the Colossus is gone. So are the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. In fact, six of the seven wonders are now dust, and the Great Pyramid is slowly joining them. Compound interest seems headed in the same direction. Great while it lasted, but nothing lasts forever.

The miracle of compounding happens only when two things occur:

- First, interest rates are a positive number significantly greater than zero.

That has been less so in recent years, and low inflation expectations are a prime reason. Which brings us to the second thing:

- Interest rates have to exceed inflation.

There is no positive benefit to compounding interest rates below the rate of inflation. My last letter explained how official government inflation measurements are low in part because our benchmarks distort some important costs like housing. Today I’ll show how the same applies in healthcare.

Then we’ll ask cui bono—who benefits—from persistently low interest rates. The answer is borrowers, which is problematic when the biggest borrowers (the Fed and the US government) of all both control rates and provide the data to justify it. Is it any wonder we have a debt problem? And a lot of the debt comes from healthcare, so it’s all a big circle. The outlook is bad and getting worse.

Of course the market, in the forms of TIPs and similar instruments, projects inflation higher than the government measures. They can’t both be right. We are going to look at broken debt and broken measurements, and then look at how Fed leaders painted themselves into a corner by shifting to a reactive stance this week.

For investors, this is about more than just policy. We could see both rising rates and rising inflation, with the Federal Reserve behind the curve. In fact, with this week’s announcements, I think the Fed is intentionally putting itself behind the curve. I can’t remember one instance where rising inflation and/or rising interest rates were good for the stock market in general.

But let’s start with the measurement dilemma.

Inflated Healthcare

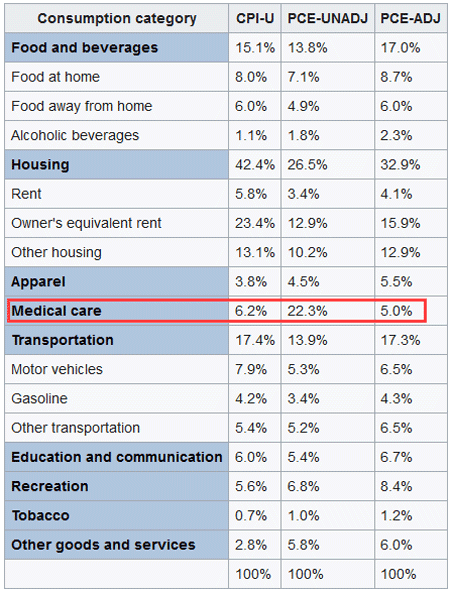

Last week I shared this table, breaking down expense weightings in the two primary inflation benchmarks, Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE). Let’s look again, but this time focused on healthcare instead of housing.

Source: Wikipedia

The first thing to notice is a huge difference between CPI and unadjusted PCE. This has to do partly with including employer insurance contributions. Healthcare is, in most cases, costlier than the consumer actually feels.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2020 the average annual premium for employer-provided family healthcare coverage was $21,342. Of this, the average worker contribution was $5,588. (Note this is only for the insurance, not any deductibles or copays.) Of course, those vary by region, employer size, etc.

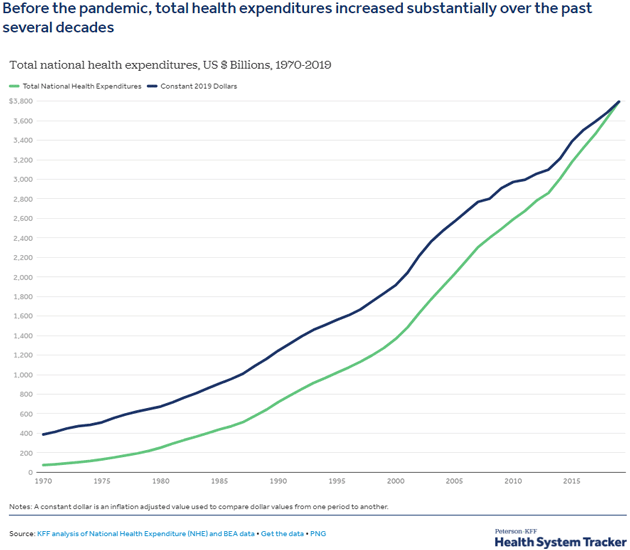

This next chart shows the actual total expenditure on healthcare for the last 50 years in the US.

Source: Health System Tracker

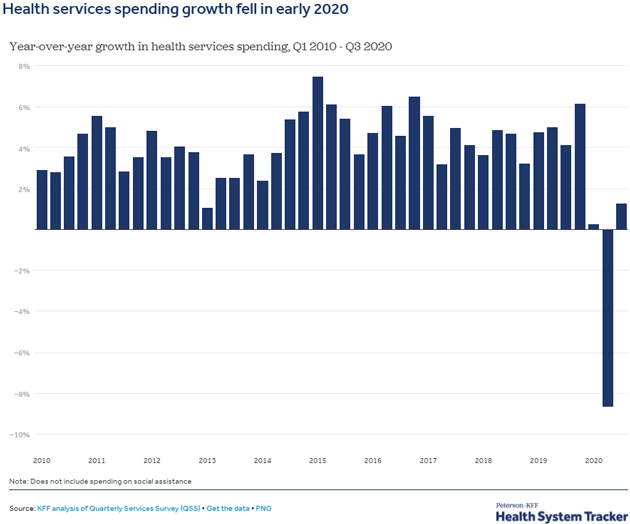

Healthcare costs have been rising more than 4% on average every year for the last decade.

Source: Health System Tracker

In CPI and PCE, a substantial part of healthcare spending isn’t captured as such, but is instead diffused in the prices of other goods and services. But let’s go back to those premiums. Kaiser says the average worker with family healthcare coverage (I know, not all workers have it) pays $5,588 a year in premiums ($465 monthly).

The median two-parent household with children, per Census Bureau data, has an income of $88,149. That would mean they spend 6.3% of their income on health insurance premiums—a little more than PCE shows and very close to the CPI medical care weighting. But we’re not done.

First, recognize this is median income. That means half the family households have income below $88,149, and thus may spend a higher percentage of it on health insurance—potentially a lot more.

More important, workers face deductibles and copays which can be quite significant. Out-of-pocket maximums vary widely, but in 89% of plans are at least $2,000 for single coverage, per KFF. So workers with even a mildly sick person in the family can spend a lot more than 6.3%.

The healthcare weightings in both CPI and PCE are probably low, but worse, they don’t necessarily measure the right prices. PCE simply assumes Medicare reimbursement rates, which are basically government-dictated price controls. Many hospitals and other healthcare providers lose money on Medicare patients and make it up from the higher payments they get from private insurers. (That’s one reason, incidentally, “Medicare for All” ideas might not work. Converting the whole industry to Medicare-level payment would put many providers out of business. That, or Medicare reimbursement prices would have to rise, significantly increasing the program’s costs.)

But the broader point is that the Fed relies on PCE to measure inflation, and we know PCE significantly understates housing and healthcare costs as experienced by typical families. This is one reason Fed officials see little inflation and expect little more in the future, and thus keep interest rates low. They encourage and subsidize excessive debt… and the biggest debtor is taking full advantage of it.

Thus when they say they want inflation to average 2%, they’re using a false measure, the equivalent of an 18-inch yardstick (or for my international readers, a 50-cm meter stick.)

Debt Trap

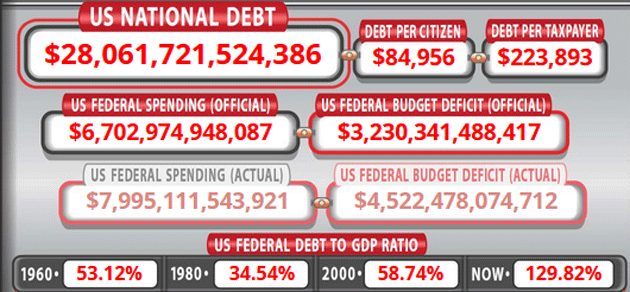

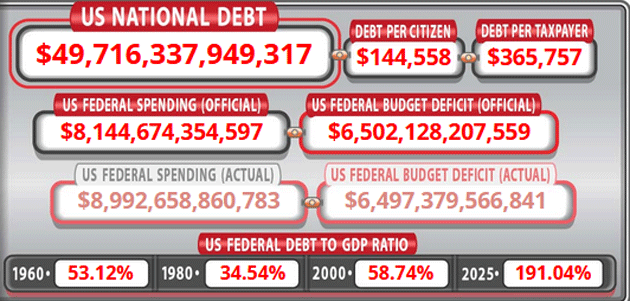

One of my favorite sites is also one of the most terrifying: US National Debt Clock. It has real-time, running tickers showing government debt and literally scores of other related statistics. Here’s a screen snap from earlier this week.

Source: US National Debt Clock

The page updates constantly so you’ll see different numbers if you go there now—but they won’t be any better. Note that the actual federal budget deficit is $4.5 trillion. That is because the off-budget deficit is well over $1 trillion right now. But at the end of the year, when the Treasury publishes actual debt numbers, it will show something like a $4.5 trillion actual increase in total debt. The market is not fooled by that “official” $3.2 trillion number. And since the $1.9 trillion stimulus has just passed, I would expect it to rise over the next few weeks.

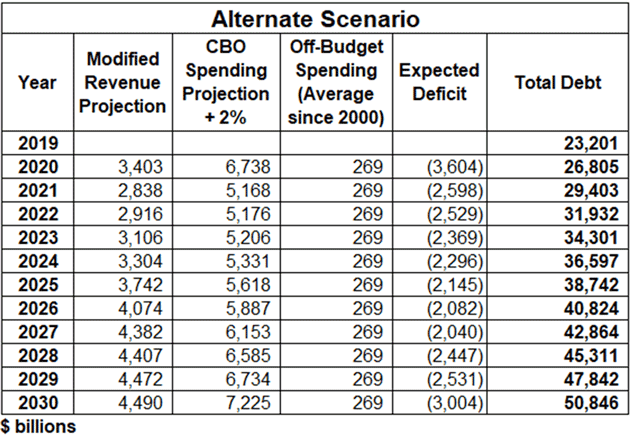

Last September in Great Reset Update, I estimated a $50 trillion federal debt by 2030. I walked through the steps to explain, as shown in this table:

Note the 2025 row. I expected a $38.7 trillion debt by then, using what I believed (and still do) are quite realistic assumptions. Also note, I used the 20-year average for the off-budget deficit. That line item can vary significantly, and is clearly doing so this year.

This week I noticed the US Debt Clock has a 2025 projection page, which simply presumes everything continues at today’s rates for four more years. It puts the debt at $49.7 trillion in March 2025.

Source: US National Debt Clock

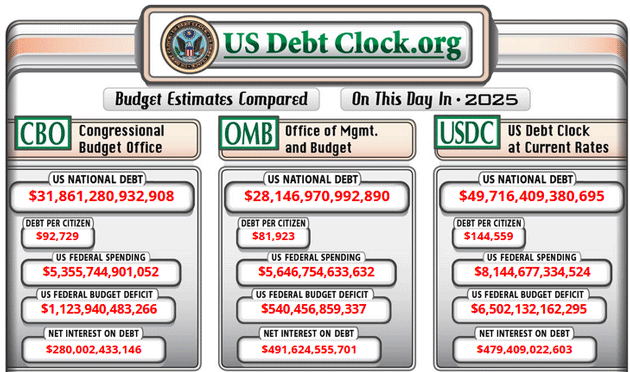

In other words, they project in 2025 roughly the same debt level I thought, as of a few months ago, we would not reach until 2030. And people called me a pessimist. But I still look pessimistic compared to the CBO and OMB. Here is how 2025 will look under their assumptions.

Source: US National Debt Clock

These laughably Pollyanna 2025 numbers are almost here right now. Does anyone see any reason the debt won’t grow considerably in the next four years? I sure don’t. And I see a bunch of reasons to think the debt growth will accelerate.

We know, for instance, President Biden and congressional Democrats just passed $1.9 trillion in additional pandemic spending, on top of the regular budget and off-budget spending. That number doesn’t include the cost of some provisions, like a major expansion in Affordable Care Act subsidies. It is presently authorized only for two years but will likely become permanent, as government programs often do. (Milton Friedman famously used to say that nothing was so permanent as a temporary government program.)

We also know an infrastructure package is probably coming, some of which may be necessary and I actually advocate, but it will further add to the debt. If your roof has a hole in it, you have to fix it unless you want to destroy the whole house. But that costs money. And we should certainly expect more social spending of various kinds. Will we get a bright, shiny, and very expensive Green New Deal? None of that fits into the projections yet, and will only make them worse.

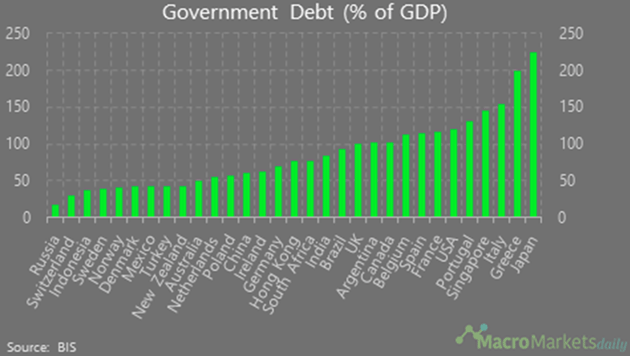

The US Debt Clock projection shows a 191% debt-to-GDP ratio in 2025, up from 129% now. Is that possible and sustainable? Maybe. Japan’s ratio is even higher. But Japan also has very low GDP growth because it is, as Lacy Hunt explains, Caught in a Debt Trap. The US has been following a few years behind. We are still on that same course.

Source: MacroMarketsDaily

I am asked all the time how long this can go on. Is there an end in sight? The simple and honest answer is that we don’t know. The US dollar is the world’s reserve currency. Japan is a secondary reserve currency, as is the euro. Japan and many European countries, (and strangely, Singapore) are all running debt-to-GDP ratios higher than the US is today. This can go on longer than we might think. But as we will see, there is a little grumbling among the troops.

The Federal Reserve Trap

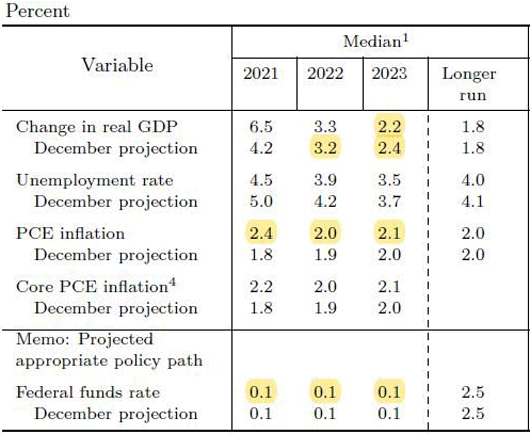

This week was a regular Federal Open Market Committee policy meeting. At the press conference, Jerome Powell was quite adamant the Federal Reserve won’t raise rates until they see a 3.5% unemployment rate and inflation averaging 2%. He was also emphatic that he wanted to see these numbers not just forecasted but as actualized, real results. He also made clear they would tolerate the economy “running hot” and inflation above 2% for a period of time. They think such inflation would be transitory and not cause to raise rates.

Let’s turn to some notes that my good friend Sam Rines published, after commenting on essentially the same thing at noted above:

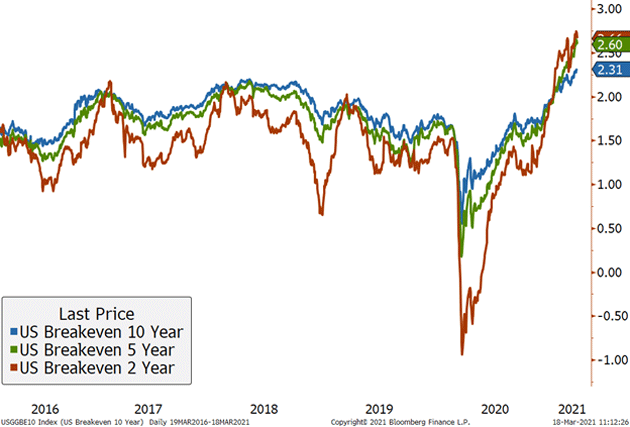

That is not a bad thing, but it does have side effects. Inflation expectations should continue to creep higher.

There is a bit of a warning embedded in the Fed’s message though. This growth surge is temporary, the sugar high is not going to last, and the Fed is not going to react to it.

There was no wavering. Not even a flinch. Any speculation that the Fed would waver from its commitment to not alter its policy until both full employment and inflation above 2% had been realized is dead. During the press conference, Powell made a few things exceedingly clear. (1) The Fed wants to see realized outcomes not forecasted wishes before raising rates. (2) The Fed does not see these outcomes occurring anytime soon. (3) The growth surge of 2021 will quickly wane. And that is how the Fed choose “winning to lose”.

Powell confirmed that they will continue to buy $80 billion worth of government bonds and $40 billion in mortgage bonds monthly. In the actual release they use the words “at least.” This gives them room to increase the bond buying. I think we will see that policy sooner rather than later. Back to Sam…

When asked about tapering QE, Powell said “substantial further progress” toward the dual mandate was needed. Critically, there was the promise of giving plenty of forewarning. That combination means QE is not going anywhere, anytime soon.

Let me quote some more from Sam as he says it more succinctly than I can:

There are side effects to the Fed’s decision. Inflation expectations should remain elevated, particularly the closer years. After all, there will be a pick-up in inflation this summer be it ever so brief and due predominantly to “base effects”. The Fed is not going to kill the cycle, and inflation expectations should rise. There is a difference, though, between the Fed not killing a cycle and inflation actually materializing. Inflation expectations are probably ahead of themselves a little. But the Fed’s new policy framework acts as a bit of a floor.

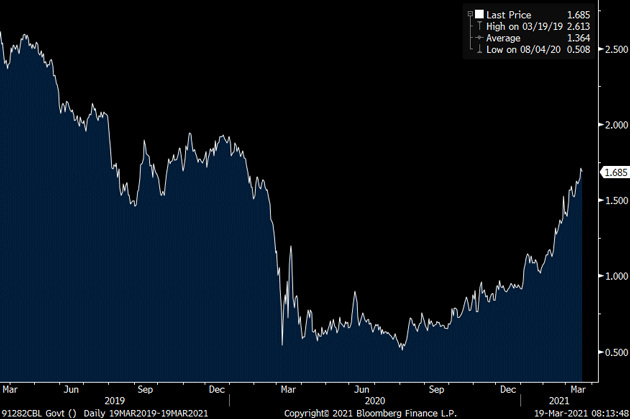

Another side effect is the pointing to the longer-term and realized outcomes. The Fed is not going to be precautionary. The Fed will be reactionary. It will be fairly obvious when the Fed begins to think about altering policy. By choosing to win the credibility battle, the Fed has lost some of the effects of easy policy by letting longer-term yields move higher.

The Fed’s dot dilemma was resolved. There is no dilemma now. There is no debate. There is no uncertainty left about Fed policy. The Fed has chosen its credibility. By “winning to lose”, the Fed is saying that forecasts are great but real outcomes are better. There will be no pre-emptive tightening of policy. The Fed is going to look through the sugar high coming to the US economy this summer—monetary policy will not change because of it.

There is almost no sense in watching the data to get a sense of Fed policy for the foreseeable future. Inflation surge this summer? “It is transitory.” Unemployment rate falls to 4.5% by the end of 2021? “Participation needs to be higher.” The Fed is not going anywhere. The Fed has the cred, and it is using it.

Far be it from me to disagree with young Sam, who is smarter than I am, but I am not so sure about that Fed credibility. Actual 10-year bond rates are rising. This is the bond market telling the Federal Reserve it isn’t comfortable with letting the economy run hot and inflation rise. Peter Boockvar sent me this chart this morning:

Source: Peter Boockvar

Fed officials have laid down the gauntlet: They will let inflation rise because it is transitory. No policy change is coming. I think they intend to jawbone the markets, using words to substitute for actions.

In high school, I played the part of Freddy Eynsford-Hill in My Fair Lady, walking the street in front of Eliza Doolittle’s house, seeking to persuade her of his love. Her response?

Freddy

Speak and the world is full of singing,

And I’m winging Higher than the birds.

Touch and my heart begins to crumble,

The heaven’s tumble, Darling, and I’m…

Eliza

Words! Words! Words!

I’m so sick of words!

I get words all day through;

First from him, now from you! Is that all you blighters can do?

Don’t talk of stars Burning above; If you’re in love,

Show me! Tell me no dreams

Filled with desire. If you’re on fire,

Show me!

This is a massive poker game. The market knows the Fed has a strong hand, but doubts the Fed’s willingness to play it. The Federal Reserve hopes markets will fold. Maybe, if the stock market falls 20% (a real possibility if inflation reaches 3.5% and the 10-year yield exceeds 2% this summer). We don’t know yet how much effect the stimulus will have. Will recipients save most of it like they did last time? Will they put it in stocks? Will consumer spending and supply chain problems push prices higher?

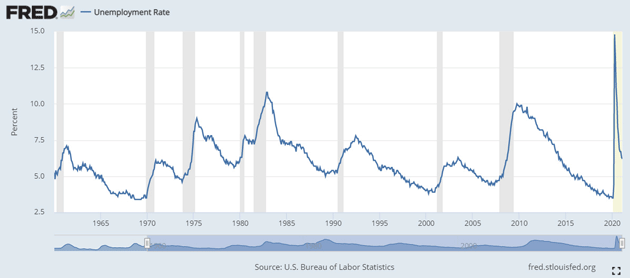

The Fed is betting the market will tolerate higher inflation. They really are going to try to hold off on raising rates until they get 2% average inflation (which they have not been able to do for a very long time) and 3.5% unemployment, which has only happened twice in the last 60 years.

Source: St. Louis Fed

One of those times was during the Vietnam War, when the draft had a major effect on unemployment. The last was in February 2020. This is a lofty unemployment goal when anything under 4.5% will be remarkable over the coming decade, given the pressures of technology and the changes arising from the pandemic, not to mention losing hundreds of thousands of small businesses. Promising to hold interest rates at the zero-bound waiting for Godot a record unemployment rate is simply irrational.

Let me close by agreeing with my friend Doug Kass:

* Monetary policy is on a collision course—a course that will likely exacerbate wealth and income inequality

* The Fed is off the rails and how—as I have written—this is not visible to most, amazes me

* Despite the consensus bullish response to Powell’s comments—both “stonks” and “bonks” could take a hit

* With value stocks extended and growth stocks vulnerable to a higher cost of capital, I remain negative on the market outlook

The next few months could be highly volatile, as the stimulus money hits, and annualized inflation rises due to low annual comparisons. Will the bond market vigilantes continue to press the Federal Reserve? Especially when they know the measurement of inflation using PCE is bogus? If it says 2.5 or 3%, it really means closer to 4%. Everyone knows this.

For the time being, we need an inflation bias in our portfolios. Long-term? I’m still in the deflationary camp, unless government spending and QE get completely out of control. Stay tuned…

Guest Post by John Mauldin Modern technology is amazing but our ancient forebears built some wondrous things, too. Long-ago historians organized them into “Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.” (Of course, their “world” was the Mediterranean and Middle East. Other wonders existed elsewhere.) Last week I noted how some call compound interest the Eighth Wonder … Continue reading “Broken Debt”

Read More