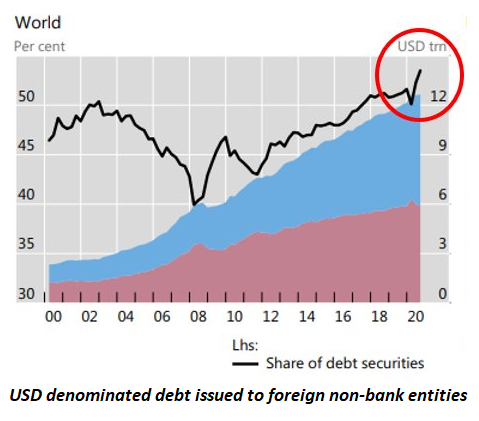

A strong currency exports inflation to those nations which do not issue the currency.

Though it’s difficult to be confident of anything in the current flux, I am pretty confident of three things:

1) price is set on the margins

2) currencies are the foundation of every economy

3) the financial forecasts issued to calm the public do not reflect operative geopolitical goals.

Every national government has “global interests.” Governments naturally do whatever they can to boost dynamics favorable to the state and nation, and obstruct or hinder dynamics injurious to the state or nation.

As a general rule, nations have relatively few levers they can pull to influence global finance, trade, growth, currencies or the geopolitical balance of power. One such lever is the interest the state pays on its sovereign bonds.

If a central bank/state increases the interest it pays on its bonds, that attracts capital seeking higher return (presuming the bond is perceived as safe from default). This inflow of capital strengthens demand for its currency, because the bonds are denominated in the state’s currency.

As the currency strengthens vis a vis other currencies, it buys more goods and services. Imports become cheaper and the nation’s exports become more costly to those using other currencies.

Another lever is to reduce the exports of commodities, especially essential commodities like energy and grains. If this reduction reduces the global supply, the price leaps.

If allies get the exports and enemies don’t, this punishes enemies and rewards allies.

A third lever is to limit imports. A consumer nation can limit imports from specific exporters, or make do with domestic supplies, or only buy from allies.

A fourth lever is to meet with allies and reach an agreement about finance and commodities to stave off imbalances that threaten the stability of the alliance.

An example of this is the 1985 Plaza Accord that weakened the U.S. dollar at the expense of the Japanese yen and European currencies. The strong dollar was crushing U.S. exports and generating destabilizing trade deficits in the U.S.

Each of these levers has geopolitical consequences.

Financial actions such as raising interest rates are presented as purely financial, but their geopolitical consequences are not lost on the nation’s political / military leadership.

Boosting or trimming exports of commodities can be presented as financial as well, even when the real purpose is geopolitical.

In other words, events which are presented as solely financial can also serve geopolitical aims beneath the domestic-centric rah-rah..

Consider how the price of oil contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the mid-to-late 1980s, the price of oil fell and stayed relatively low for years.

In 1986, oil fell under $10/barrel. Adjusted for inflation, this was lower than prices paid in the late 1950s.

Although this ample oil supply was fundamentally a result of super-major oil fields discovered in the 1960s and 1970s coming online, it had a geopolitical consequence few fully appreciate: it pushed the Soviet Union over the fiscal cliff into collapse.

Oil and natural gas exports were the primary source of the Soviets’ hard cash it needed to buy goods and commodities from other nations.

Once the oil revenues dried up, the Soviet Union was no longer financially viable.

Was this lengthy “glut” of oil just good luck for the U.S., or was a policy agreement with Saudi Arabia and other oil exporters that “nudged” the price lower also a factor?

What do you reckon–pure luck or luck “nudged” to achieve a geopolitical goal? Given the high stakes and the vulnerability of the USSR to low oil prices, is it plausible that it was entirely happy happenstance?

In the 35 years since the Plaza Accord, the U.S. has endeavored to keep the dollar relatively weak for a number of reasons: to limit trade deficits, and avoid putting undue pressure on emerging countries with debts denominated in USD and nations that imported commodities priced in USD, which is virtually all commodities.

This weak-dollar policy has changed, with profound implications. The soaring USD is adding a currency “surcharge” on top of rising prices for commodities such as oil and grain.

Take Japan as an example: the yen has weakened 20% against the USD. This means every commodity priced in USD is 20% higher in price for those using yen.

Add the increase in cost due to global scarcities and that’s a double-whammy hit of inflation.

These sharp increases in inflation / price of essentials are recessionary, as demand craters. People simply don’t have enough earnings to pay higher costs for essentials and maintain their discretionary spending on goods and services.

Recall that price is set on the margins. If supply of oil falls 5 million barrels per day (BPD), price rises. But if demand falls 10 million BPD, the price of oil plummets.

As the price of oil falls, oil exporters receive much less money, and so they compensate by pumping more oil. This serves to further depress prices.

Who would benefit from a rising US dollar and a global recession, and who would be hurt? The US would benefit from a higher USD because that lowers the cost of all imports. Everyone else using weaker currencies would pay more for imported commodities.

As demand for oil falls, price plummets. That helps consumer nations and hurts oil exporters.

As the USD rises, it drags every currency pegged to the USD higher with it, making their exports more expensive. That would pressure China’s exports, forcing China to adjust its currency peg, reducing the purchasing power of everyone using yuan/RMB.

Is the looming global recession merely “bad luck” or could an unavoidable global recession be “nudged” to serve geopolitical aims? The forces that have been unleashed (higher interest rates, scarcities, strong dollar) will take time to work through the global economy. The USD may drop and oil may rise over the next few months, but where will global demand and oil be in a year?

Many people expect the dollar to weaken and the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates back to zero once the recession becomes undeniable.

I am not so sure. A case can be made that interest rates have completed a 40-year cycle of decline and are now in a secular cycle higher.

A case can also be made that the weak-dollar policy has ended and the dollar will move higher, accelerating the financial and geopolitical consequences described above.

A strong currency exports inflation to those nations which do not issue the currency. Luck, coincidence, or “nudge”? Maybe it doesn’t matter. maybe what matters is that it’s happening.

A version of this essay was first published as a weekly Musings Report sent exclusively to subscribers and patrons at the $5/month ($54/year) and higher level. Thank you, patrons and subscribers, for supporting my work and free website.