Edward Snowden via Continuing Ed. gave criticisms against Central Bank Digital Currencies, in an article that he published about CBDCs on Oct 9, 2021. In this post, Snowden delivers a comprehensive description of his position and arguments on the state of CBDCs and how they might be implemented by the US Federal government. Snowden refers to the CBDCs as a “‘useful policy tool’ for casually annihilating the savings of every wage-worker in the country if they don’t spend them fast enough.”:

1. This week’s news, or “news,” about the US Treasury’s ability, or willingness, or just trial-balloon troll-suggestion to mint a one trillion dollar ($1,000,000,000,000) platinum coin in order to extend the country’s debt-limit reminded me of some other monetary reading I encountered, during the sweltering summer, when it first became clear to many that the greatest impediment to any new American infrastructure bill wasn’t going to be the debt-ceiling but the Congressional floor.

That reading, which I accomplished while preparing lunch with the help of my favorite infrastructure, namely electricity, was of a transcript of a speech given by one Christopher J. Waller, a freshly-minted governor of the United States’ 51st and most powerful state, the Federal Reserve.

The subject of this speech? CBDCs—which aren’t, unfortunately, some new form of cannabinoid that you might’ve missed, but instead the acronym for Central Bank Digital Currencies—the newest danger cresting the public horizon.

Now, before we go any further, let me say that it’s been difficult for me to decide what exactly this speech is—whether it’s a minority report or just an attempt to pander to his hosts, the American Enterprise Institute.

But given that Waller, an economist and a last-minute Trump appointee to the Fed, will serve his term until January 2030, we lunchtime readers might discern an effort to influence future policy, and specifically to influence the Fed’s much-heralded and still-forthcoming “discussion paper”—a group-authored text—on the topic of the costs and benefits of creating a CBDC.

That is, on the costs and benefits of creating an American CBDC, because China has already announced one, as have about a dozen other countries including most recently Nigeria, which in early October will roll out the eNaira.

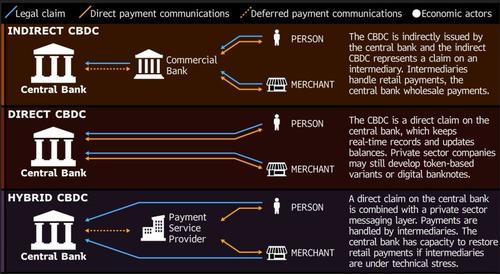

By this point, a reader who isn’t yet a subscriber to this particular Substack might be asking themselves, what the hell is a Central Bank Digital Currency?

Reader, I will tell you.

Rather, I will tell you what a CBDC is NOT—it is NOT, as Wikipedia might tell you, a digital dollar. After all, most dollars are already digital, existing not as something folded in your wallet, but as an entry in a bank’s database, faithfully requested and rendered beneath the glass of your phone.

In every example, money cannot exist outside the knowledge of the Central Bank

Neither is a Central Bank Digital Currency a State-level embrace of cryptocurrency—at least not of cryptocurrency as pretty much everyone in the world who uses it currently understands it.

Instead, a CBDC is something closer to being a perversion of cryptocurrency, or at least of the founding principles and protocols of cryptocurrency—a cryptofascist currency, an evil twin entered into the ledgers on Opposite Day, expressly designed to deny its users the basic ownership of their money and to install the State at the mediating center of every transaction.

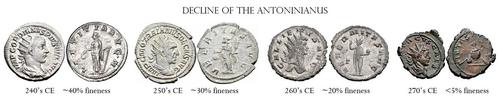

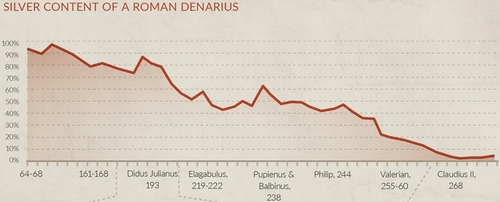

2. For thousands of years priors to the advent of CBDCs, money—the conceptual unit of account that we represent with the generally physical, tangible objects we call currency—has been chiefly embodied in the form of coins struck from precious metals. The adjective “precious”—referring to the fundamental limit on availability established by what a massive pain in the ass it was to find and dig up the intrinsically scarce commodity out of the ground—was important, because, well, everyone cheats: the buyer in the marketplace shaves down his metal coin and saves up the scraps, the seller in the marketplace weighs the metal coin on dishonest scales, and the minter of the coin, who is usually the regent, or the State, dilutes the preciosity of the coin’s metal with lesser materials, to say nothing of other methods.

Behold the glory of thelaw

The history of banking is in many ways the history of this dilution—as governments soon discovered that through mere legislation they could declare that everyone within their borders had to accept that this year’s coins were equal to last year’s coins, even if the new coins had less silver and more lead. In many countries, the penalties for casting doubt on this system, even for pointing out the adulteration, was asset-seizure at best, and at worst: hanging, beheading, death-by-fire.

In Imperial Rome, this currency-degradation, which today might be described as a “financial innovation,” would go on to finance previously-unaffordable policies and forever wars, leading eventually to the Crisis of the Third Century and Diocletian’s Edict on Maximum Prices, which outlived the collapse of the Roman economy and the empire itself in an appropriately memorable way:

Tired of carrying around weighty bags of dinar and denarii, post-third-century merchants, particularly post-third-century traveling merchants, created more symbolic forms of currency, and so created commercial banking—the populist version of royal treasuries—whose most important early instruments were institutional promissory notes, which didn’t have their own intrinsic value but were backed by a commodity: They were pieces of parchment and paper that represented the right to be exchanged for some amount of a more-or-less intrinsically valuable coinage.

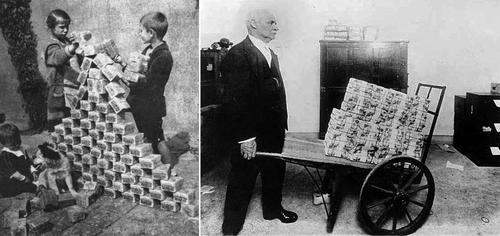

The regimes that emerged from the fires of Rome extended this concept to establish their own convertible currencies, and little tiny shreds of rag circulated within the economy alongside their identical-in-symbolic-value, but distinct-in-intrinsic-value, coin equivalents. Beginning with an increase in printing paper notes, continuing with the cancellation of the right to exchange them for coinage, and culminating in the zinc-and-copper debasement of the coinage itself, city-states and later enterprising nation-states finally achieved what our old friend Waller and his cronies at the Fed would generously describe as “sovereign currency:” a handsome napkin.

Sovereign currency, as known to history

Once currency is understood in this way, it’s a short hop from napkin to network. The principle is the same: the new digital token circulates alongside the increasingly-absent old physical token. At first.

Just as America’s old paper Silver Certificate could once be exchanged for a shiny, one-ounce Silver Dollar, the balance of digital dollars displayed on your phone banking app can today still be redeemed at a commercial bank for one printed green napkin, so long as that bank remains solvent or retains its depository insurance.

Should that promise-of-redemption seem a cold comfort, you’d do well to remember that the napkin in your wallet is still better than what you traded it for: a mere claim on a napkin for your wallet. Also, once that napkin is securely stowed away in your purse—or murse—the bank no longer gets to decide, or even know, how and where you use it. Also, the napkin will still work when the power-grid fails.

The perfect companion for any reader’s lunch.

3. Advocates of CBDCs contend that these strictly-centralized currencies are the realization of a bold new standard—not a Gold Standard, or a Silver Standard, or even a Blockchain Standard, but something like a Spreadsheet Standard, where every central-bank-issued-dollar is held by a central-bank-managed account, recorded in a vast ledger-of-State that can be continuously scrutizined and eternally revised.

CBDC proponents claim that this will make everyday transactions both safer (by removing counterparty risk), and easier to tax (by rendering it well nigh impossible to hide money from the government).

CBDC opponents, however, cite that very same purported “safety” and “ease” to argue that an e-dollar, say, is merely an extension to, or financial manifestation of, the ever-encroaching surveillance state. To these critics, the method by which this proposal eradicates bankruptcy fallout and tax dodgers draws a bright red line under its deadly flaw: these only come at the cost of placing the State, newly privy to the use and custodianship of every dollar, at the center of monetary interaction. Look at China, the napkin-clingers cry, where the new ban on Bitcoin, along with the release of the digital-yuan, is clearly intended to increase the ability of the State to “intermediate”—to impose itself in the middle of—every last transaction.

“Intermediation,” and its opposite “disintermediation,” constitute the heart of the matter, and it’s notable how reliant Waller’s speech is on these terms, whose origins can be found not in capitalist policy but, ironically, in Marxist critique. What they mean is: who or what stands between your money and your intentions for it.

What some economists have lately taken to calling, with a suspiciously pejorative emphasis, “decentralized cryptocurrencies”—meaning Bitcoin, Ethereum, and others—are regarded by both central and commercial banks as dangerous disintermediators; precisely because they’ve been designed to ensure equal protection for all users, with no special privileges extended to the State.

This “crypto”—whose very technology was primarily created in order to correct the centralization that now threatens it—was, generally is, and should be constitutionally unconcerned with who possesses it and uses it for what. To traditional banks, however, not to mention to states with sovereign currencies, this is unacceptable: These upstart crypto-competitors represent an epochal disruption, promising the possibility of storing and moving verifiable value independent of State approval, and so placing their users beyond the reach of Rome. Opposition to such free trade is all-too-often concealed beneath a veneer of paternalistic concern, with the State claiming that in the absence of its own loving intermediation, the market will inevitably devolve into unlawful gambling dens and fleshpots rife with tax fraud, drug deals, and gun-running.

It’s difficult to countenance this claim, however, when according to none other than the Office of Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes at the US Department of the Treasury, “Although virtual currencies are used for illicit transactions, the volume is small compared to the volume of illicit activity through traditional financial services.”

Traditional financial services, of course, being the very face and definition of “intermediation”—services that seek to extract for themselves a piece of our every exchange.

4. Which brings us back to Waller—who might be called an anti-disintermediator, a defender of the commercial banking system and its services that store and invest (and often lose) the money that the American central banking system, the Fed, decides to print (often in the middle of the night).

You’d be surprised how many opinion-writers are willing to publicly pretend they can’t tell the difference between an accounting trick and money-printing.

And yet I admit that I still find his remarks compelling—chiefly because I reject his rationale, but concur with his conclusions.

It’s Waller’s opinion, as well as my own, that the United States does not need to develop its own CBDC. Yet while Waller believes that the US doesn’t need a CBDC because of its already robust commercial banking sector, I believe that the US doesn’t need a CBDC despite the banks, whose activities are, to my mind, almost all better and more equitably accomplished these days by the robust, diverse, and sustainable ecosystem of non-State cryptocurrencies (translation: regular crypto).

I risk few readers by asserting that the commercial banking sector is not, as Waller avers, the solution, but is in fact the problem—a parasitic and utterly inefficient industry that has preyed upon its customers with an impunity backstopped by regular bail-outs from the Fed, thanks to the dubious fiction that it is “too big too fail.”

But even as the banking-industrial complex has become larger, its utility has withered—especially in comparison to crypto. Commercial banking once uniquely secured otherwise risky transactions, ensuring escrow and reversibility. Similarly, credit and investment were unavailable, and perhaps even unimaginable, without it. Today you can enjoy any of these in three clicks.

Still, banks have an older role. Since the inception of commercial banking, or at least since its capitalization by central banking, the industry’s most important function has been the moving of money, fulfilling the promise of those promissory notes of old by allowing their redemption in different cities, or in different countries, and by allowing bearers and redeemers of those notes to make payments on their and others’ behalf across similar distances.

For most of history, moving money in such a manner required the storing of it, and in great quantities—necessitating the palpable security of vaults and guards. But as intrinsically valuable money gave way to our little napkins, and napkins give way to their intangible digital equivalents, that has changed.

Today, however, there isn’t much in the vaults. If you walk into a bank, even without a mask over your face, and attempt a sizable withdrawal, you’re almost always going to be told to come back next Wednesday, as the physical currency you’re requesting has to be ordered from the rare branch or reserve that actually has it. Meanwhile, the guard, no less mythologized in the mind than the granite and marble he paces, is just an old man with tired feet, paid too little to use the gun that he carries.

These are what commercial banks have been reduced to: “intermediating” money-ordering-services that profit off penalties and fees—protected by your grandfather.

In sum, in an increasingly digital society, there is almost nothing a bank can do to provide access to and protect your assets that an algorithm can’t replicate and improve upon.

On the other hand, when Christmas comes around, cryptocurrencies don’t give out those little tiny desk calendars.

But let’s return to close with that bank security guard, who after helping to close up the bank for the day probably goes off to work a second job, to make ends meet—at a gas station, say.

Will a CBDC be helpful to him? Will an e-dollar improve his life, more than a cash dollar would, or a dollar-equivalent in Bitcoin, or in some stablecoin, or even in an FDIC-insured stablecoin?

Let’s say that his doctor has told him that the sedentary or just-standing-around nature of his work at the bank has impacted his health, and contributed to dangerous weight gain. Our guard must cut down on sugar, and his private insurance company—which he’s been publicly mandated to deal with—now starts tracking his pre-diabetic condition and passes data on that condition on to the systems that control his CBDC wallet, so that the next time he goes to the deli and tries to buy some candy, he’s rejected—he can’t—his wallet just refuses to pay, even if it was his intention to buy that candy for his granddaughter.

Or, let’s say that one of his e-dollars, which he received as a tip at his gas station job, happens to be later registered by a central authority as having been used, by its previous possessor, to execute a suspicious transaction, whether it was a drug deal or a donation to a totally innocent and in fact totally life-affirming charity operating in a foreign country deemed hostile to US foreign policy, and so it becomes frozen and even has to be “civilly” forfeited. How will our beleagured guard get it back? Will he ever be able to prove that said e-dollar is legitimately his and retake possession of it, and how much would that proof ultimately cost him?

Our guard earns his living with his labor—he earns it with his body, and yet by the time that body inevitably breaks down, will he have amassed enough of a grubstake to comfortably retire? And if not, can he ever hope to rely on the State’s benevolent, or even adequate, provision—for his welfare, his care, his healing?

This is the question that I’d like Waller, that I’d like all of the Fed, and the Treasury, and the rest of the US government, to answer:

Of all the things that might be centralized and nationalized in this poor man’s life, should it really be his money?