“This is an ecological and equal constitution with social rights at its very core,” the president of Chile’s constituent assembly said of the new document, which the nation’s adults will vote on in September.

“This is an ecological and equal constitution with social rights at its very core,” María Elisa Quinteros, president of the 155-member assembly, told The Guardian on Monday, prior to a formal presentation of the draft at a ceremony in the port city of Antofagasta.

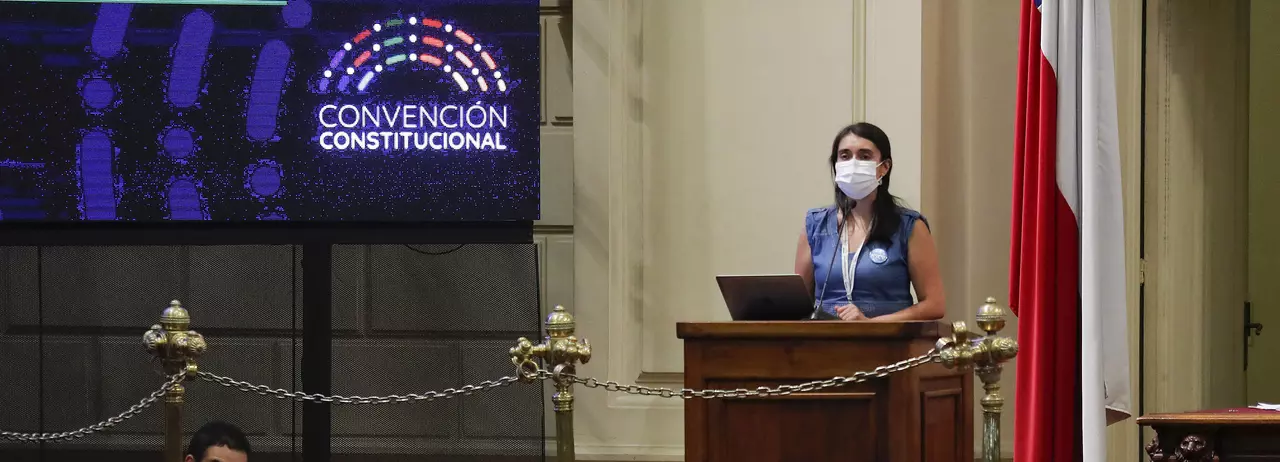

Ya comenzó el Pleno n°104 de la Convención Constitucional desde las Ruinas de Huanchaca, Antofagasta. 🏛

— María Elisa Quinteros Cáceres (@MEQChile) May 16, 2022

Hoy se presenta formalmente el borrador de nueva Constitución. 💬 pic.twitter.com/e4sMorLgwX

The draft constitution that delegates crafted over the past year promises to enshrine a wide range of rights, including universal access to public healthcare, education, and pensions, as well as stronger environmental safeguards and policies to promote gender and racial equity.

Among the draft constitution’s 499 articles are provisions that would abolish the senate in favor of a unicameral legislature, codify reproductive rights, require the state to mitigate and adapt to the climate crisis, and constitutionally recognize for the first time Chile’s Indigenous peoples, including through compensation for land dispossession.

Its fate will be decided on September 4, when all Chilean adults must vote yay or nay on the draft. If supported by a majority, it will be ratified as Chile’s new constitution. If not, the country’s current document—so privatization-friendly that even water rights are bought and sold by investors—will remain in force.

Chile’s existing constitution—forcibly imposed in 1980, seven years after democratically elected socialist President Salvador Allende was overthrown in a U.S.-backed coup—has worsened economic exploitation and environmental degradation. Moreover, because Pinochet’s neoliberal policy blueprint remains largely intact more than three decades after his military junta ended in 1990, it has also obstructed the creation of a more egalitarian and sustainable society to this day.

The long struggle for a new, democratic constitution received a major boost when a sustained wave of social unrest erupted in October 2019. Although a transit fare hike triggered the protests, Chileans insisted that they were taking to the streets in response to 30 years of post-dictatorship austerity rather than 30 pesos.

Then-President Sebastian Piñera was forced to schedule a plebiscite to let citizens decide whether to rewrite the nation’s constitution, but not before his government violently repressed protestors, killing 36 individuals and blinding hundreds of others.

Nearly 80% of Chileans rejected Pinochet’s constitution in an October 2020 referendum. In another vote last May, they elected a progressive slate of 155 delegates to the constituent assembly tasked with writing a new constitution, raising hopes that the citizen-led body would produce an emancipatory charter that reduces inequality and protects the environment.

Quinteros said Monday that Chile’s draft constitution has “provided answers to the demands of the 2019 demonstrations.”

Although the constituent assembly shot down more ambitious proposals to democratize mining rights, Thea Riofrancos, an associate professor of political science at Providence College whose research focuses on resource extraction in Latin America, argued on social media that other institutional changes proposed in the draft constitution will “deeply transform the sector” if they are ultimately enacted. Mineral-rich Chile is the world’s leading copper producer and second-biggest lithium producer.

It’s true Chile’s constitutional convention didn’t approve state expropriation of mines. But—pending September referendum—the huge expansion of environmental, water, Indigenous rights; rights of nature; ecosystem governance & bigger state role will deeply transform the sector 1/ pic.twitter.com/sVJxlZzCce

— Thea Riofrancos (@triofrancos) May 15, 2022

During his December victory speech, Chile’s leftist President Gabriel Boric—a key leader of the 2011 student movement for free, quality public higher education—told a crowd of supporters that “to destroy the world is to destroy ourselves.”

“We don’t want more sacrifice zones,” he added. “We don’t want projects that destroy our country, destroy communities.”

Article 107 of the draft charter would make Chile the second country, after Ecuador, to constitutionally recognize the rights of nature. And that’s far from the only article focused on improving biodiversity and ensuring a healthy environment for current and future generations.

Other articles call for mining exclusion zones, the protection of glaciers and the Antarctic, guaranteed access to renewable energy, and the free exchange of seeds.

"The State guarantees the right of peasants and indigenous people to freely use and exchange traditional seeds" – so reads the new draft constitution of Chile, which will be put to a nationwide vote on 4 September 2022 https://t.co/OIE7XH1SaH

— GRAIN (@GRAIN_org) May 16, 2022

A trio of committees has been tasked with ironing out the remaining details before July 4, when the entire constituent assembly is scheduled to vote on a final draft constitution to present to the citizenry, teleSUR reported.

Beginning Tuesday, the Harmonization Commission is expected to streamline the document and improve its coherence by eliminating redundancies and rectifying contradictions. Before June 9, the Preamble Committee is expected to write an introductory text. The Transitional Rules Committee, meanwhile, is expected to develop a plan for a smooth transition from the old to a new constitution.

Although Pinochet’s market-led constitution is deeply unpopular, the constituent assembly must find a way to build public support for its alternative charter over the next several months.