Experts discuss whether Xi will continue to lead his country and what it means for relations with Russia and the wider world. The 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, the pinnacle event in the country’s political life and held only every five years, kicks off in Beijing on October 16. Experts will be tuning in to pick up any signals related not only to the political standing and prospects of China’s leader Xi Jinping, who is likely to run for a third term, but also to the way the country is planning to build its relations with the US and Russia in the future.

A new Mao – a new revolution?

Western speculation believes that the event could signify a triumph for Xi as he will most likely remain at the helm of the party for a third term. Should that happen, it would go against the tradition which has formed in Chinese politics over the last 30 years. Up to now, the reins of power in the country were handed over to a new generation of leaders at the end of the second term.

Thus, such a move would herald a new era in the history of modern China.

Starting from 2018, it has become increasingly clear that Xi is going to defy this tradition. That year, amendments were made to the Chinese Constitution lifting the two-term limit on the presidency.

However, according to Aleksandr Lomanov, the Deputy Director for Scientific Work at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO RAS), the extension of Xi’s rule for another term is not indicative of the general direction of Chinese politics in the next five year.

“For the world at large, the important thing is not whether Xi Jinping is going to stay for another term. Most of the world’s countries don’t really care who is in charge in China. What is important is the kind of policies China is going to pursue in the future, and how stable the country is going to be,” Lomanov explained.

Also, the congress is expected to review the party’s work and achievements over the last five years as well as to announce the new composition of its ‘board of directors’ – the Political Bureau (Politburo) Standing Committee of the CPC Central Committee, composed of the party’s top officials who make all the important decisions in the country. Today, it’s made up of seven members (historically, this number has ranged from five to nine).

It is believed that at least three of the party members currently serving on the Standing Committee will resign for various reasons, including China’s second most important man – Premier of the State Council Li Keqiang. He is required by law to step down as premier in 2023, since the term limit was only removed for the president.

2,300 CPC delegated are expected to take part in the upcoming congress, with the total number of party members exceeding 90 million people.

The Congress will focus on China’s domestic agenda

Experts appear to be united in their forecasts that if there are any unexpected moves at all – such as restoring the Chairman of the CPC Central Committee, a post abolished in 1982 – they will most likely only concern the party’s inner workings. Foreign policy will not be high on the agenda, in all likelihood.

The historical and political self-sufficiency characteristic of China throughout its history is still there in the 21st century. The Chinese have never really cared about much happening outside of their country, which they traditionally call ‘The Middle Kingdom’ (中国).

While espousing a supposedly international ideology, the CPC does not really deviate from this tradition. In his speech at the 2017 Party Congress, Xi Jinping mentioned the building of a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind – his key foreign-policy concept – only in chapter 12 out of 13.

Lomanov agrees that foreign affairs have never taken center stage at China’s National Congress events.

“Focus on foreign affairs goes against the tradition of the CPC, in stark contrast to the late-Soviet-era congresses. Just compare any Chinese report to Brezhnev’s speech at the 26th Congress in 1981, where the international agenda was mentioned as early as the first chapter. The Chinese congresses are about China first and foremost. About the role of the CPC in public life, the economy, and the country’s social policies. It would be wrong to say that foreign policy is absent, but it usually appears closer to the end of reports. It’s not a priority at all at the CPC congresses, historically,” he explained.

The Director of the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies of the Higher School of Economics, Vasily Kashin, told RT that China is still in the phase of active establishment and promotion of its ideology in foreign affairs.

The Community with a Shared Future for Mankind (人类命运共同体) has arguably become the main foreign political concept of Xi’s rule, presenting the Chinese vision of a fair world order to the international public. The phrase first appeared in a report of the ex-General Secretary of the CPC Hu Jintao at the 17th Congress in 2007, referring to a common future of continental China and Taiwan. Five years later, Hu expanded the meaning by adding ‘for mankind.’ The concept was later promoted by his successor Xi Jinping.

The plans calls for a new mindset that would lead to a more fair reformation of the global leadership. This is, in essence, a positive agenda, but it is criticized by the West and India, who seek to bar the phrase itself from being mentioned in any UN resolutions. Beijing’s rivals see it as promotion of the PRC’s propaganda aimed at building a new world order.

The Covid-19 pandemic presented an opportunity for China to bring the concept to life. The virus was transnational, and providing aid to other nations proved beneficial to the donors themselves, while the finger-pointing by former President Donald Trump and attempts by the US to pull through on its own under his administration went against shared global interests. At the same time, China’s own ‘zero tolerance’ policy has also been a rather peculiar strategy, and the PRC refrains from actively promoting it abroad.

Aleksandr Lomanov also agrees about the concept’s standing: “There is no reason to believe that any changes will suddenly be made at the Congress to the Community with a Shared Future for Mankind. China isn’t going to abandon the concept soon and it will remain a priority for as long as Xi Jinping remains in power – meaning for the rest of 2020s,” he said.

The narrative of a ‘shared future’ is relevant for China in the context of the Taiwan issue as well, which itself balances on a thin line between domestic and foreign affairs. The island is actively forming its new identity almost completely unrelated to continental China. It’s one of the Party’s priorities to offer a carrot in addition to a stick to the islanders to prevent their complete secession. Lomanov argues the West is trying to play the Taiwan card to its own benefit, so the potential is growing of this issue becoming one the most dangerous conflicts in the world.

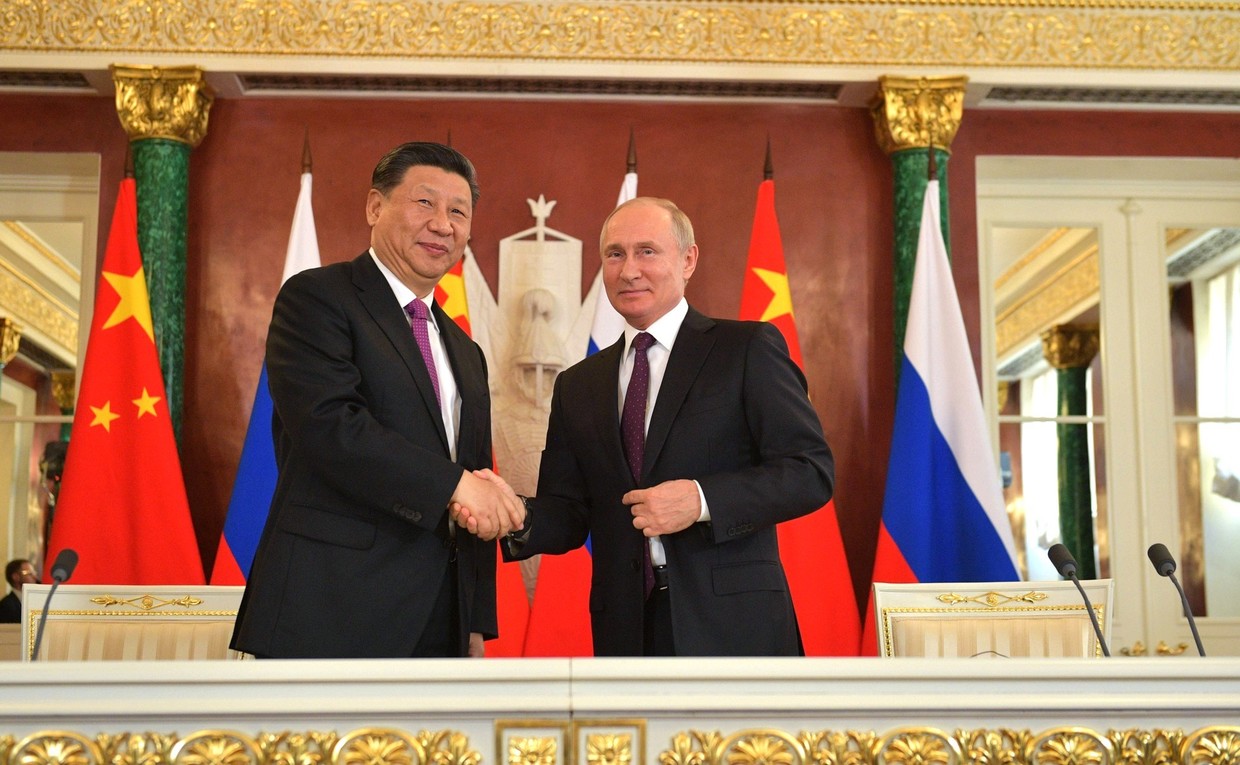

Putin is my friend, but…

On September 30, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed treaties on accession of four former Ukrainian regions to Russia. Prior to the signing, he delivered a lengthy speech at Georgievsky Hall in the Kremlin Palace, extensively criticizing the world order formed after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Russia has essentially signaled that it is ready to pick up the fallen banner of the Soviet Union and spearhead the anticolonial struggle on the international stage in the 21st century.

“The West is ready to cross every line to preserve the neo-colonial system which allows it to live off the world, to plunder it thanks to the domination of the dollar and technology, to collect an actual tribute from humanity, to extract its primary source of unearned prosperity, the rent paid to the hegemon. The preservation of this annuity is their main, real and absolutely self-serving motivation. This is why total de-sovereignisation is in their interest. This explains their aggression towards independent states, traditional values and authentic cultures, their attempts to undermine international and integration processes, new global currencies and technological development centers they cannot control. It is critically important for them to force all countries to surrender their sovereignty to the United States,” Putin said.

In his brief historical retrospective, the Russian president also brought up Beijing. He spoke of China’s defeats at the hands of Britain and France in the Opium Wars of the mid-19th century. Afterwards, China was forced to open its ports for Europeans to engage in the opium trade, a drug that caused great misery for its people. According to Chinese historians, those events ushered in a “century of humiliation,” as China had to sign a series of unequal treaties which would only be terminated in 1949 with the creation of the People’s Republic.

Realistically, however, how can this uncharacteristic reference to Asian history help Putin persuade China to challenge the West in earnest and threaten the existing world order?

Experts doubt that Beijing will abandon its policy of prudence and caution, and there are a number of reasons for that.

“Much of what Vladimir Putin said in his speech at the accession ceremony is in line with China’s own attitudes. But when China talks about similar matters, the wording is often much broader and generally ambiguous. Naturally, Beijing is aware that its confrontation with the West is getting more intense. However, at the level of rhetoric, China tries to avoid being as explicit when expressing its position. Moscow and Beijing have similar viewpoints in that both believe the policies of the West are flawed, as they create artificial barriers to global trade, financial and economic ties and investment opportunities,” Lomanov said.

“China also criticizes the West for building ‘small fortresses with high walls’, referring to blocs like NATO and AUKUS, exclusive alliances designed to unite Western countries and those loyal to them, effectively cutting off everyone else.

“China has always stressed the need to reform the existing system of global governance, as it is deeply unfair to developing countries. Despite all its leaps in economic development, China considers itself both a socialist country and the world’s leading developing nation. Therefore, at a practical level, the positions of Russia and China are indeed very close,” the expert from IMEMO RAS believes.

Vasily Kashin explains that the reason why China prefers a more ‘vague’ phrasing when it describes its stance is that Beijing does not consider the West as a single monolithic power.

“Some of what Putin said back then at the accession ceremony did resonate with China’s worldview. But even if internally the Chinese can relate to his words, they will not explicitly voice their support for them. The fact is that China simply does not have an overall policy towards the West – it makes a sharp distinction between Europe and the United States. And what worries Beijing the most about Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine is the major increase of US influence in Europe. In other matters, the Chinese are largely in agreement with the Russians, but they do try to avoid overly confrontational rhetoric,” said the expert.

Moreover, in his statements, the Chinese president will most likely keep the number of references to other countries to a minimum.

“There will be no official words of support for Russia in the documents passed by the CPC national congress; at most, it may be mentioned as one of China’s major partners. As for its statements about the US, in theory, there could be some openly critical assessments. They could say, for example, that the actions of the US serve only to inflame further tensions,” Kashin speculated.