In the previous publication we considered common approaches in geopolitical foresight methodologies specific to Western countries.i Clearly, alternative models are also possible, with a purely scientific, rational approach being clearly limited as it is historically closely linked to the Western worldview paradigm. At least since the Enlightenment, Eurocentrism has constantly permeated communities in other regions and transformed knowledge systems in a particular way, bringing them to some kind of common denominator. This homogenisation also affected the analytical school in a broad sense, which began to adhere more to mathematical modelling and work with statistical data (incidentally, weather forecasting is largely based on work with earlier meteorological survey indicators).

Nevertheless, even in the West there are critical views on how to view a particular science. Danish scientist Sven Larson, for example, argues: “Economics is not a natural science. It is, always has been and always will be a social science. Unlike physics, which many economists would like to compare their discipline to, economics cannot be studied with strict mathematical models and strict universally applicable laws. Economists will argue vehemently that economics can be explained in mathematical terms. They are wrong: economics can only be properly studied on the axiom that human nature – unlike physical nature – is not quantifiable. “ii

It is the qualitative rather than quantitative approach that is the fundamental difference that separates the Western school, which claims to be universal, and the non-Western, as yet fragmented theories that appeal to tradition and conservative values. The non-Western schools have one thing in common – irrespective of the region and religious component, they all agree that progress is not a good thing. Rather, on the contrary, progress (political, scientific, technical, etc.) leads a traditional conservative society in the wrong direction, as it questions the established social foundations and hierarchy and substitutes values. The notion of apostasy (apostasy) in Christianity and kafir (doubter, infidel) in Islam are related to this. The example of the United States and Western European countries clearly shows the devaluation of Christian values in these politically and technically progressive countries, where the concepts of “freedom of speech”, “human rights” and so on have been quite sophisticatedly substituted.

It is indicative that traditional societies do not deny the possibility of prosperity, only that, unlike proponents of progress, they put a slightly different meaning into this notion.

The key criterion in this respect is time and its functions. If the liberal-democratic West measures everything from the position of linear and unidirectional time, which goes through the material space, for the conservative societies the notions of cyclicity and eternity are of fundamental importance. In India, where the majority of inhabitants profess Hinduism, this period refers to the last phase of the cycle, called Kali Yuga. It is an epoch of degradation and decline. But as we can see this does not stop India from actively positioning itself on the international stage and developing technology. Considering that the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party has strongly religious characteristics, one may assume that they are guided by Hindu traditions and beliefs in formulating their strategies.

In countries dominated by Christianity and Islam, eternity is central to the daily lives of believing citizens. Political parties may not state this in their manifestos or programmes. However, it is clear that the mindset of the people, even if not directly expressed, is linked to the concept of the frailty of this world, the end times and the future eternal life. Note that eschatology is characteristic of Christians of all faiths, as well as of Muslims of various schools of law (madhhabs).

Western political science, while analysing processes related to faiths, does not make religious life the main focus of its analysis of current trends and predictions. But given that the Abrahamic tradition is a way of life, such an interpretation (albeit with a justification in the form of secularism and material rationalism) is seen as a clear omission.

Now let us try to think from the perspective of a conservative Christian worldview, since this perspective takes into account Russia’s cultural and historical background (without, of course, excluding the role of other confessions practiced by the peoples of the Russian Federation). The first thing to do is to establish the initial coordinates – where we are, what is the general teleology (goals) of the world and, in particular, of our people, whether there are common ground with other societies, what is desirable (good) and what is unacceptable (evil) – the latter two can be defined as challenges and threats.

With this approach, the analytical framework will clearly not correlate with the foresights to which we are accustomed. After all, we are talking about in-depth questioning which political scientists are simply not used to – after all, they can only see problems to be solved by various technical, political or bureaucratic means. And in our case we are talking about something beyond these limits, artificially set by European philosophers-materialists in the New Age. At least we can talk about metapolitics in the broad sense, which does not neglect other factors of human life – art, metaphysics and religious philosophy.

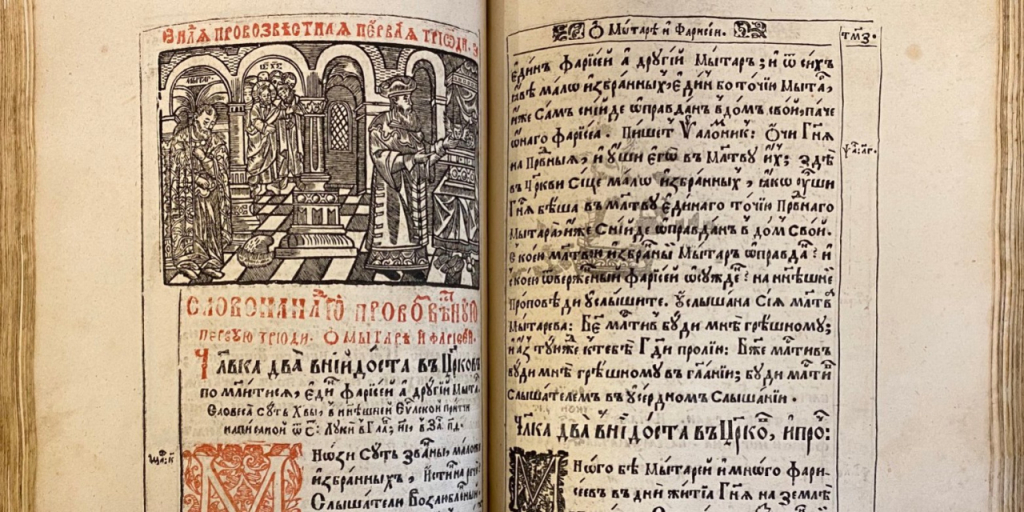

And here it is necessary to pay attention to interesting factors, such as visionaryism in art and prophecy in religion. Poets and prophets were often drawn together by the metaphorical expressions with which they tried to describe the world and its future. History has clearly proved them right. Therefore, it would be strange not to take these categories of thinking into account when developing the conservative school of political forecasting. This is a very delicate question, not a simple one, as it may seem at first sight. Because one has to describe irrational images in a rational language.

Nevertheless, in countries with a Christian culture any political upheaval has always been linked to God’s mercy and righteous wrath which falls on the heads of people for some transgressions. The origins of this relationship lie in Judaism, where, according to the commandments Moses received from God, specific injunctions had to be followed. The penalties for breaking them were varied, up to and including the scattering of the Jewish people and the destruction of their temple in Jerusalem. Interpreting these events through the prism of prophecy (since all this had been foretold before) points to a clear connection between religion and politics. In the New Testament there are also certain indications of proper behaviour and understanding of the world around us. And the interpretations of the Apocalypse by John the Evangelist bring a certain doom on the one hand, but on the other it shows the importance of remaining steadfast in times of serious trials. Although it is rather difficult to say exactly when the End Times will come and how long they will last: yet numerous world events constantly give reason to talk about it, assessing political cataclysms, conflicts and key global events, whether it is an economic crisis or a coronavirus pandemic, from the perspective of eschatology.

Focusing on this renders meaningless the numerous factors which are cited by Western analysts when preparing forecasts. Agree that when it comes to Salvation, the Second Coming, the need for collective prayer to defeat the enemy, questions such as gross domestic product, economic ratings, the investment climate, etc. become not just trivial, but meaningless.

But, on the other hand, everyone understands that to win modern conflicts one must have a sufficiently sustainable economy and powerful weapons. That is why a very balanced and adequate synthesis is needed, based on the application of exact sciences, but supported by traditional values and confessional attitudes.

What then can be a domestic approach to develop such a scenario of the future? Even if we limit ourselves to the orthodox worldview, it will also not be as simple as it seems at first sight. For example, how to perceive the concept of Moscow – the Third Rome? Is it an eschatological attitude or a political project? If the latter, is there no risk of falling into the trap of geopolitical exceptionalism that we see in the US example? Should we reckon with the Slavophiles’ statement about synodality as a unifying model for the people, a certain manifestation of wholeness? Was this a deliberate politicization of a purely ecclesiastical concept?

The Eurasians lucidly explained that synodality, i.e. catholicity, conveys the inner nature of the Church, as distinguished from ecumenicality. The Church cannot and should not have a political and generally concrete practical programme.iii But it is clear that in the present conditions of open confrontation with the West and the ongoing operation in Ukraine we need clear guidelines linking the plans for the coming years in the political-economic sphere (the experience of the five years may be useful) and the aspirations of the people, which include an understanding of Eternity, a cultural-historical perspective reflecting the heroic experience of previous generations and mechanisms to translate theoretical programmes into reality, o This provides a framework not only for anticipation as such, but also for consistent action steps that transform knowledge into the experience of everyday activity.

iI https://russtrat.ru/scenarii/16-sentyabrya-2022-1524-11189

iiII https://europeanconservative.com/articles/commentary/time-to-end-the-nobel-prize-in-economics/

iiiIII Савицкий П.Н. Континент Евразия. – М.: Аграф, 1997. С. 32, 49.