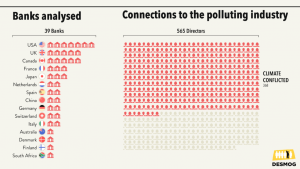

The majority of directors at the world’s biggest banks have affiliations to polluting companies and organizations, a DeSmog investigation shows. The findings raise concerns over a systemic conflict of interest at a time when the international financial sector is under increasing pressure to stop funding fossil fuels.

DeSmog’s analysis found 65% of directors from 39 banks had 940 past or current connections to industries that could be considered climate-conflicted.

Directors with affiliations to companies involved in extracting oil, gas and coal — the world’s most polluting energy sources — were well-represented across bank boardrooms, with 16% of all board members having current or previous roles in the polluting energy sector.

There were also significant ties to banks and investment vehicles supporting polluting industries, as well as to thinktanks and lobbying groups with a history of campaigning against climate action.

Geoffrey Supran, research associate in the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University, said the existence of such ties is “predictable, yet shocking.”

“The fossil fuel industry has a well-established track record of ingratiating itself with society’s opinion leaders and decision makers, and because of the revolving doors between the corporate leaderships of incumbent industries,” he told DeSmog.

“Having its fingers in all the pies allows the fossil fuel industry to quietly put its thumb on the scales of institutional decision making, helping delay action and protect the status quo.”

Systemic problem

The investigation assessed the employment history and affiliations of 565 bank directors from the boards of major retail banks in the UK, US, Canada, Europe, South Africa, China and Japan.

Directors were found to have a wide range of experience in high carbon sectors, including in polluting energy, aviation, mining, manufacturing and banks and investment companies known to support the fossil fuel industry. These positions ranged from director and advisory roles, to employment by the companies and trade association or thinktank memberships or affiliations (with data collected up to Jan 31).

Banks are increasingly saying they will decarbonize by 2050, yet a large number continue to finance fossil fuels, the primary source of carbon emissions. To accelerate action, shareholder activists have filed climate resolutions for upcoming AGMs at three of the institutions analyzed. UK bank Barclays and Japan’s biggest bank Mitsubishi UFJ are considering resolutions for stricter regulations on lending. U.S. bank Wells Fargo is facing a resolution to remove its Chair.

The resolutions come as a report by Rainforest Action Network showed that some of the world’s largest commercial and investment banks had invested $3.8 trillion into fossil fuel companies in the five years since the Paris Agreement, the global commitment to limit temperature rise to 2C and preferably to 1.5C by 2100.

Simon Youel, of advocacy group Positive Money, said the banks’ failure to act showed they could not be trusted to “go green” of their own accord.

“Bankers too often have vested interests in pumping up the carbon bubble, which is why we need central banks to play their role as regulators of the financial system and stamp out risky fossil fuel lending,” he told DeSmog.

Climate conflicted banks

DeSmog’s analysis found that 15% of directors had worked with companies identified by the Climate Action 100+ initiative as some of the world’s worst polluters, and one in 20 (6%) had ties to companies financing extraction of coal, the most polluting fossil fuel.

The research also found that more than one in five directors (28%) had worked at other banks known to support fossil fuel extraction, and that 16% had been involved with investment vehicles supporting polluting industries.

All eight board members of Dutch bank ABN AMRO have had positions in environmentally damaging companies, with six having current affiliations. Heavy industry was also well-represented on the bank’s board, with four directors having past or current connections to the polluting energy sector, four with ties to industrial organizations, and three to construction companies.

Responding to DeSmog’s findings, a company spokesperson for ABN AMRO said sustainability was “a core element” of its strategy, with “full support of the bank’s Supervisory Board.”

A Credit Suisse spokesperson said they did not respond to media requests regarding individual board members. In a statement to DeSmog, they added:

“As a global financial institution, Credit Suisse recognizes its share of responsibilities in combating climate change, and we acknowledge that financial flows also need to be brought in line with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. We believe that our role as a financial intermediary is to act as a reliable partner in the transition to a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy.”

A spokesperson for ING told DeSmog that the bank was “committed to steering its entire lending book of over €600 billion towards the Paris Agreement goals,” and would reduce financing to upstream oil and gas by 19% by 2040 from 2019 levels.

“The Supervisory Board of ING consists of a mix of persons with experience in various sectors and environments,” they said, adding that in selecting the board ING “strove for a balance in nationality, gender, age and educational and work background.” ING director Mariana Gheorghe had nothing further to add to this, they said.

All other banks referenced in this story were approached for comment.

Directors at JP Morgan Chase, a company recently found to have spent $317 billion on fossil fuel financing since the Paris Agreement, held multiple affiliations to companies funding or associated with hydrocarbon extraction, including major industrial conglomerate General Electric and Warren Buffett’s holding company, Berkshire Hathaway.

Coal accounted for 43% of the generation capacity of Berkshire Hathaway Energy’s assets in 2019, and for 48% of the capacity of assets owned by PacifiCorp, an electric utility owned by the group. General Electric, one of the world’s largest makers of coal-fired power plants, announced last year it would no longer build any new plants, but continues to service existing operations.

Six of JP Morgan’s directors also had connections to investment and holding companies, and four to think tanks and associations with a history of campaigning to weaken climate change measures. Several board members were also affiliated to major polluting food and beverage organizations, including Walmart, Starbucks and General Foods.

Regional variations

Directors’ affiliations reflected the sectoral emphasis of domestic economies. For instance, banks in oil-rich Canada had the highest number of ties to extractive industries — with 35% of directors holding past or current positions in the polluting energy sector, including links to high-carbon oil extraction from Alberta’s tar sands reserves.

The vast majority of directors at Scotiabank (93%), and TD (92%) had past or current affiliations to high carbon sectors, while 40% of Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC) directors held past or current ties to the fossil fuel sector. Three in 12 directors at the Bank of Montreal (25%) had current affiliations to polluting energy sector organizations, as did four of 14 (29%) board members at Scotiabank.

Many British bank directors (45%) were found to have held positions at other banks known to support polluting industries, with 28% of directors at U.S. banks holding positions with organizations in the same sector. One in five (20%) of U.S. bank directors also had links to investment vehicles that also have stakes in polluting sectors.

Across the dataset, 7% of directors also had links to thinktanks and lobby groups that had campaigned to weaken climate change measures. In the U.S. and Canada, 17% and 24% of directors respectively had such connections.

Ties to companies that work in or serve high-carbon industries were most pronounced in the U.S. (with 14% of directors holding such positions), while one in 10 of the Canada bank directors held links to steel, metals and mining.

Within Europe, polluting connections were more evenly distributed, though the continent had the highest proportion of ties to the aviation sector (with 9% of directors being affiliated). Connections to the food and drink industry were also noteworthy — 15% of U.S. directors had ties to the sector, including through previous jobs with Coca Cola, Pepsi and KFC, which have come under fire for their lack of climate commitments.

Of the banks analyzed outside of Europe and the Americas, Bank of China had the highest number of overall polluting ties, with 23% of directors connected to other fossil fuel supporting banks, and several board members affiliated with high-carbon industries such as shipping and agribusiness. Two board members had held positions in companies financing extraction of coal, which in 2019 provided 58% of the country’s energy mix.

Climate-conflicted directors

DeSmog’s analysis focused on board members as banks’ ultimate decision-makers on strategic, financial and regulatory matters. The investigation broadly identified three types of climate-conflicted directors: those who have spent their careers in fossil fuels, those who have extensive ties across polluting industries and directors that do not have long-standing relationships with the most polluting sectors but have significant occasional affiliations to high-carbon companies.

All directors referenced in the investigation have been contacted for comment.

Fossil fuel executives

Oil and gas giants such as Shell, BP and Exxon, as well as some lesser known polluters, were well represented on banks’ boards through directors with lengthy careers in the industry.

Bank of Montreal board member Lorraine Mitchelmore has over 30 years experience in the oil and gas industry, having spent 14 years with Shell Canada, seven of those as President. She also worked with oil giant Chevron and BHP (formerly BHP Billiton), an Anglo-Australian mining, metals and petroleum company, and Petro-Canada, a subsidiary of oil sands company Suncor Energy, where she now serves as director.

Barclays director Brian Gilvary has also spent his career in oil and gas, having worked for BP for 34 years in various senior financial and commercial roles. Last year he was appointed Chair of INEOS Energy, a new company formed by the chemicals giant to accelerate the group’s technologies under the energy transition. Gilvary is also a current fellow of the Energy Institute, a global association of energy industry professionals. The institute organizes “International Petroleum Week,” an annual conference aimed at bringing oil and gas professionals together “to flourish the sector and resolve various issues faced by the industries.”

Within Europe, ABN AMRO director Arjen Dorland spent 29 years working for Shell, including as Vice President. Before that, he worked as a project manager for Exxon and currently serves on the board of gas and electricity company and E.ON subsidiary Essent.

Crédit Agricole director Caroline Catoire has also spent her career working in polluting industries. Catoire sits on the board of oil and gas exploration company Maurel & Prom, and previously spent 18 years at oil giant Total, including as the company’s director of corporate finance. Her role coincided with Societe Generale director Jerome Contamine, a current director at Total who previously worked in its exploration and production division.

Director at the Dutch multinational ING, Mariana Gheorghe, served as CEO and President of Romanian integrated oil company, OMV Petrom, from 2006 to 2018. Gheorghe now sits on the board of British power generation company Contour Global, which still has stakes in coal assets in Bulgaria and Colombia, despite announcing a pivot away from coal last year. An ING spokesperson told DeSmog Gheorge had nothing further to add to the bank’s statement reiterating its climate goals and commitment to diversity on its board.

In South Africa, Standard Bank director Nomgando Matyumza, previously worked as the CEO of Transnet Pipelines, the principle operator of the country’s fuel pipeline system. She also worked for state-run energy company Eskom, where fellow board member Thulani Gcabashe served as CEO from 2000-2007. Matyumza is also currently on the board of oil and gas company SASOL Limited, along with fellow Standard Bank board member Gesina Trix Kennealy.

Industry executives

The analysis also revealed the prevalence of business figures who have spent their careers in polluting non-energy sectors, from metals and mining, to agribusiness and aviation.

Lakshmi Mittal, an Indian steel magnate on the board of Goldman Sachs, has extensive ties to industry as CEO of ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steelmaking company. Mittal is also a member of the World Steel Association, which has argued against carbon pricing mechanisms in the name of maintaining “a level playing field.” Mittal is also a member of the European Roundtable of Industrialists, which previously opposed increasing the ambition of the EU’s carbon pricing system, and which thinktank InfluenceMap found had a “limited but broadly negative engagement on climate policy.”

Likewise, Morgan Stanley director Mary Schapiro, appointed under Barack Obama as the first woman to have served as the Chair of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, has also sat on the board of a range of major energy, industrial and food and drink companies, such as General Electric, Duke Energy and Kraft Foods.

In Europe, Deutsche Bank director Paul Achleitner has worked across big names in German agribusiness, car manufacturing and energy. After a long career in banking and insurance, including as the managing director of Goldman Sachs’ German operations, the Austrian businessman spent thirteen years as a director of German energy and coal-producing giant RWE, and 10 years on the board of car company Daimler, best known for its Mercedes Benz brand. He is now coming to the end of a two-decade term as a board member of the board of pharmaceutical and chemical giant Bayer, which has been involved in a number of controversies over its production of hazardous pesticides and climate-washing PR campaigns.

Former President of Mexico Ernesto Zedillo, a board member of Citi, is recognized as a leading voice on globalization, and regularly speaks on climate change and economic leadership, including in his role as professor in the field of international economics and politics at the University of Yale. But Zedillo has multiple connections to high carbon sectors, including through his current advisory roles on the boards of BP, Credit Suisse, Coca Cola and Rolls Royce.

Occasional connections

The analysis also reveals a number of bank directors with significant occasional ties to high-carbon sectors without having spent their careers working in them.

They include Credit Suisse board member Michael Klein, who has used his decades of experience working at Citigroup to advise on major oil and gas deals, including Saudi Aramco’s recent initial public offering, the biggest in history, and the merger between mining companies Glencore and Xstrata.

Santander director Marty Chavez spent 20 years at Goldman Sachs, including as its chief executive — but also four years on the board of PNM Resources in the early 2000s — a coal-supporting energy holding company providing electricity services in New Mexico.

Standard Chartered director Gay Huey Evans has three decades of experience in financial services, including with the Financial Services Authority, Citibank and Barclays Capital. She also serves as Chair of the London Metal Exchange, and is a board member for oil giant ConocoPhillips, which between 1965-2017 was responsible for more than 15 billion tons of carbon emissions.

Barclays director Tushar Morzaria worked as a chartered accountant before holding senior roles at JP Morgan and Credit Suisse, both among the biggest financiers of fossil fuels. He currently sits on the board of BP, the oil company responsible for over 34 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions between 1965 – 2017.

Climate leadership lacking

The extent of polluting affiliations exposed by the analysis underscore the need for closer scrutiny of board members, said Molly Scott Cato, Professor of Green Economics at the University of Roehampton and a former Green Party MEP.

“It’s shocking to see the very close links between banks and fossil fuel and other heavily polluting industries and helps to explain why, even in the middle of a climate emergency, it has been so difficult to undertake the rapid defunding of the very industries that are driving us to climate destruction,” she told DeSmog.

“This research needs to become a lesson for banks to conduct audits of their staff, not only to understand their potential biases, but also to ensure that they have undertaken mandatory sustainability education.”

Adam McGibbon of Market Forces, a group campaigning to prevent investment in environmentally-damaging projects, agreed that the extent of the connections that fossil fuel companies had to bank boardrooms presented a potentially concerning conflict of interest. He told DeSmog:

“Financial institutions are critical to driving the transition to clean energy, so it’s terrifying that their directors’ views are being shaped by the fossil fuel industry.

“How can banks reasonably claim to support the Paris Agreement when their directors are linked to an industry with a vested interest in the Paris Agreement failing?”

Originally published by DeSmog.

The post Directors at Top Global Banks Linked to World’s Biggest Polluters, Investigation Shows appeared first on Children’s Health Defense.