On 10 November 2022, the European Commission unveiled a new action plan, “Military Mobility 2.0”. In parallel, the “EU Cyber Defence Strategy” has been released.

Officially outlined, the documents aim “to cope with the deteriorating security environment following Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and improve the EU’s ability to protect its citizens and infrastructure”.

According to Margrethe Vestager, executive vice president of the European Commission, “Today, there is no EU defence without cyber defence. Therefore, the two strategies are interconnected and complementary.

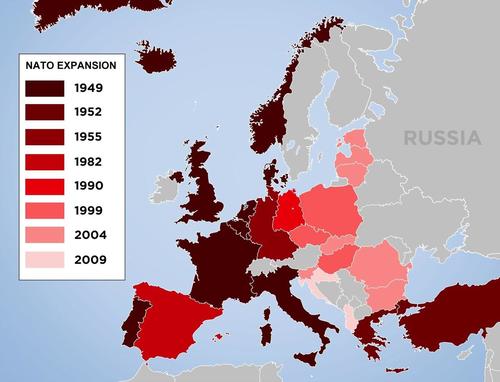

In sum, the Action Plan on Military Mobility should help European militaries respond better, faster and on a sufficient scale to crises arising at the EU’s external borders and beyond. It should strengthen the EU’s ability to support Member States and partners with respect to the transport of troops and their equipment. It also aims to strengthen cooperation with NATO and will facilitate communication and dialogue with key partners. In the context of the current EU stance towards Ukraine, as well as the strengthening of NATO’s eastern flank, this initiative signifies a course for further confrontation with Russia, as well as drawing states that are not yet members of either the EU or NATO into Brussels’ orbit of influence.

Building on the achievements of the first action plan launched in 2018, the new military mobility covers the period 2022-2026 and includes:

– Identifying possible infrastructure gaps, informing future actions to prioritise improvements and integrating fuel supply chain requirements to support large-scale movements of armed forces in the short term;

– Digitalisation of administrative processes related to customs, logistics and military mobility systems;

– Measures to protect transport infrastructure from cyber attacks and other hybrid threats;

– Facilitating access to strategic delivery vehicles and maximising synergies with the civilian sector to enhance military mobility, especially by air and sea;

– Improving energy efficiency and climate change resilience of transport systems;

– Strengthening cooperation with NATO and key strategic partners such as the US, Canada and Norway, while facilitating engagement and dialogue with regional partners and enlargement countries such as Ukraine, Moldova and the Western Balkans.

The plan proposes further action to ensure the rapid, efficient and unhindered movement of potentially large-scale forces, including military personnel and their equipment, both in the context of the EU Common Security and Defence Policy and for national and multinational activities, especially within NATO.

The strategic approach of this Action Plan focuses on the need to develop a well-connected military mobility network, consisting of:

– multimodal transport corridors, including roads, railways, air routes and inland waterways routes with dual-use transport infrastructure capable of serving military transport

– Transport hubs and logistics centres that provide the necessary support to host and transit countries to facilitate the deployment of troops and materiel;

– Harmonized regulations, by-laws, procedures and digital administrative mechanisms;

– improved sustainability, resilience and preparedness of civilian and military transport and logistics capabilities.

Thus, it will require significant resources to reorganise logistics routes and hubs in the EU, as well as adjusting legislation to military needs. In fact, it is a militarisation of internal policies, both of the EU itself and of each individual member of the community. It is assumed that all this will be implemented within the framework of PESCO (Permanent Structured Cooperation) and in close coordination with NATO. Infrastructure will be renewed through a review of the Trans-European Transport initiative. Intra-EU border crossing procedures will also be streamlined. In parallel, large-scale exercises will be conducted, including multinational manoeuvres within NATO.

In terms of cybersecurity, it is planned to pay special attention to the civil transport sector and its support systems, including traffic management systems (air, rail, maritime transport), container terminal management systems, control systems for locks, bridges, tunnels, etc. The recently adopted updated Network and Information Security Directive (NIS2) in the transport sector is to be rapidly implemented. It is also planned to exchange the necessary information to ensure the fullest possible situational awareness among the military and civilian transport sectors. This will be carried out by the European Cyber Crisis Liaison Organisation Network (EU – CyCLONe). The importance of using EU space capabilities for this purpose is also mentioned.

In general terms, there is a noticeable trend towards increased Euro-Atlantic interdependence, as in addition to NATO, which is a key partner organisation, other participants in the PESCO military mobility project are mentioned, notably the USA, Canada and Norway. It is expected that Britain, too, will soon join this PESCO project once the relevant procedures are completed.

It is indicative that, in parallel, France has also presented its national defence strategy. It, too, focuses on cooperation with the EU and NATO, as well as on cyber security, nuclear weapons and hybrid warfare. But France’s strategy is more detailed and almost three times larger than the EU Plan.

Overall, it contains ten strategic objectives.

1. Maintain a credible and trustworthy nuclear deterrent. The conflict in Ukraine “demonstrates the need to maintain a credible and trustworthy nuclear deterrent to prevent a major war” that is “legitimate, effective and independent”, while reiterating “the need to maintain the ability to understand and contain the risk of escalation”.

2. Increase resilience to both military and non-traditional (information manipulation, climate change, resource hunting, pandemics, etc.) security challenges by promoting a defensive spirit and ensuring national cohesion. To this end, France is implementing a national resilience strategy designed to strengthen its ability to withstand any kind of disruption to the country’s normal life. In addition, the universal national service will be expanded in some uncertain way; Macron has said he will elaborate on this in the first quarter of 2023.

3: Ensuring that French industry supports the war effort over the long term by building strategic stocks, moving the most sensitive production lines and diversifying suppliers. This is reminiscent of the idea of a “wartime economy” that Macron first put forward at the Eurosatory conference in June 2022.

4. Increasing cyber resilience. “There are no means available to create a cyber defence that would prevent every cyber attack on France, but improving its cyber security is essential to prepare the country for new threats,” the document says. To do so, “efforts in the public and private sectors need to be intensified.” Notably, the document says that “despite the important work already done, the state’s cyber security has significant room for improvement” and “there is a need to significantly improve the cyber security of all public services”.

5. NATO’s key role in European defence, France’s role in it and the strengthening of the European pillar. The paper states that “France intends to maintain a unique position within the North Atlantic Alliance. It holds a demanding and prominent position because of the specificity and independence of its defence policy, in particular its nuclear deterrent”. It is added that, based on its operational credibility, rapid response capability and financial contribution, “France intends to increase its influence and that of its European allies to influence major changes in NATO’s posture and the future of strategic stability in Europe”. The document notes that France “excludes the extension [of membership] to other geographical areas, in particular to the Indo-Pacific region.

6. Strengthen European sovereignty and develop Europe’s defence industry. “European strategic autonomy depends on a robust European defence industrial capability that meets its own needs” and to this end “France supports the creation of a short-term instrument for the joint acquisition of European equipment”.

7. Be a reliable partner and a credible security provider. The document mentions a deepened relationship with Germany, key partnerships with Italy and Spain, strategic partnerships with Greece and Croatia, a capacity building partnership with Belgium, mentions Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia and notes that a “constructive dialogue” should be “quickly re-established with the UK”. The strategic partnership with the United States “will remain fundamental and should be ambitious, sober and pragmatic”. Reference is made to relations with African countries, the Persian Gulf, the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, and the Indo-Pacific region.

8. Improving intelligence. France must continue deep reforms of its intelligence services and pursue an “ambitious” recruitment and retention policy. It also needs to invest in new technical tools that “will have to exploit the potential of quantum computing and artificial intelligence”.

9. Defending against and acting in hybrid wars (deliberately ambiguous combinations of direct and indirect, military and non-military, legitimate and illegitimate, often difficult to define modes of action). A more flexible, responsive and integrated organisation will be created to “identify, characterise, trigger appropriate protection mechanisms (…) and respond effectively”. Tools are also being developed to counter private military companies being used as proxies by hostile powers. The protection of critical infrastructures is also being prioritised.

10. Freedom of action and ability to conduct military operations. It is a question of the willingness of the French armed forces not only to engage in high-intensity combat, but also to deploy their forces as soon as possible and be the first to enter the battlefield “with or without possible support from allied countries”.

Here, too, serious ambitions to emerge as Europe’s military leader are visible, with a bid to be self-reliant and develop broad partnerships. Although against the backdrop of France’s failures in Africa, which have shown a weak fighting capability, some positions will be quite difficult to fulfil.

Given Germany’s earlier announced increase in military readiness, from increasing the military budget to recruiting future Bundeswehr soldiers, we see a more coherent picture that presents a change in the structure of the EU armed forces with the clear implication that this is being done against Russia.

Translation by Lorenzo Maria Pacini