“Everything Will Go To Zero” – Macquarie Strategist Envisions Era Of Tech-Driven Deflation

With the latest CPI numbers stoking interest in the “transitory” vs. “not-so-transitory” inflation debate, it’s perhaps fitting that the latest MacroVoices interview featured Macquarie global equities strategist Viktor Shvets, who explained why he believes the world is entering a new era where the deflationary pressures produced by technology-induced improvements in productivity will create a “race to zero” that will see prices continue to fall.

However, Shvets believes that over the next 10 to 20 years, inflation and deflation will act more like opposite sides of a pendulum that occasionally swings back and forth.

On the inflationary side, one new development is the dominance of fiscal policy over monetary policy in terms of their impact on the market. An innovation inspired by COVID-19 that Shvetz expects will increasingly become the norm in the US. As the younger generation embraces “socialism”, the US government will likely increasingly pay for medicine and even a universal basic income for those who don’t work (and perhaps even for those who do).

Just this week, the Biden Administration introduced new handouts for families with young children.

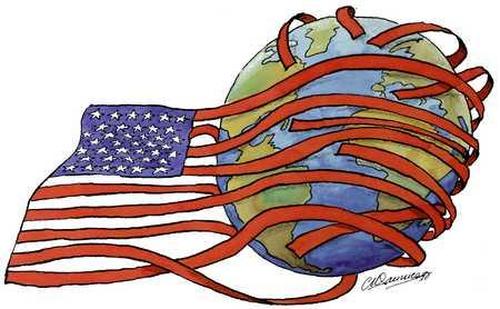

And the third element is a deglobalization and localization that’s going to continue to strengthen. So what you have in the next 10 to 20 years, two very powerful forces are going to struggle. One is very strong, long term disinflationary force, which ultimately is going to win. And the other one is more inflation created from various things we’re going to do over the next 10 to 20 years. Now, the interesting question, Erik is who is going to decide whether inflation or disinflation wins at any given point in time? Now, my personal view for quite some time has been that private sector will never walk again on this system.

While Shvetz doesn’t believe in systematic inflation, he believes in systematic disinflation.

The reason is that technology has turbocharged the spirit of competition. And the same deflationary forces that gave us free music, free equity trades and free digital news will soon get to work on other aspects of the economy, until prices are falling on nearly all goods and services.

So if one agrees with me, that cost of capital must fall forever, then it’s like pouring a kerosene on a bonfire of technological age. And what technology does incredibly well is reducing marginal pricing power of both labor and capital, and corporates, and brands. And so what happens over time, those reduction in marginal pricing power converges into average pricing power, which also declines. And eventually, almost everything becomes free. There is no prices, just like information today is almost entirely free. Just like publications today, almost entirely free, just like trading on the New York Stock Exchange quite, not quite, but almost entirely free. Just like a lot of music is almost entirely free. So we already have massively reduced marginal pricing power in a lot of industries. We’ve already reduced marginal pricing power of labor.

Shvetz even cited research from McKinsey and others to justify his “everything goes to zero” thesis about long-term price deflation.

That’s why McKinsey in their review, was estimating that the impact of information age could be 3000 times the impact of industrial age. In other words, much broader and much faster, 300 times broader, 10 times faster. And so when I say everything goes to zero, eventually, the productivity growth rates will be so high, that there will be no need to value any of that stuff. And the economists are not going to function the same way as I’ve done over the last two or 300 years.

Moving on to a discussion of contemporary markets, Townsend asked Shvetz for his view on interest rates. Is the only rational direction for Treasury yields higher? To this, Shvetz offered a detail answer grounded in history. As government debt burdens have soared, the only way forward for central banks is to follow the BoJ and artificially repress yields as central banks buy up the entire market.

Well, it reminds me what people were saying about Japan. Remember in 1990s and early 2000. The view was that if God forbid Japan ever ignites inflation, they immediately go bankrupt because the government will be spending 50, 60, 70% of their budget just servicing the debt. Now, how much do you think Japanese Government today is spending on servicing debt 4%. Not 50, not 40, not 80, 4%. And the debt burden is much, much larger than what it used to be. Now a lot of people say, well, you know, Japan is unique.

Okay, let’s look at Eurozone. How unique is Eurozone? Look at the UK? How unique is the United Kingdom? And if you think of the US. One of the things that is becoming very clear, is that what happened in Japan since early 90s. What happened in Eurozone since global financial crisis over the last five or six years started to happen in the US as well. And a basic sort of signal that the US is sending now, just like the other economies do, it’s not about supply of money. It’s about demand for money. It’s not about supply of credit.

It’s about demand for credit. And increasingly, the more we leverage, the more we financialize, the more we erode marginal demand for credit. Now, what that implies is that interest rates not only they cannot go up, but they will not go up. And by the way, if they do, remember, we always have perpetuals, which have no value at all, because they’re never redeemable.

On the horizon, we have MMT or modern monetary theory. We already have BoJ. Remember the has been monetizing more debt that the Government of Japan has been issuing. That’s why they’re sitting on 50 to 53% of JGB market. Eventually, you don’t need the JGB market at some point in time.

Echoing a point made by Jeffrey Gundlach, Shvetz points to the fact that on top of its burgeoning debt, the US also has hundreds of billions of dollars in unfunded liabilities.

Readers can listen to the entire interview below courtesy of MacroVoices:

Tyler Durden

Thu, 07/15/2021 – 21:40

“Everything Will Go To Zero” – Macquarie Strategist Envisions Era Of Tech-Driven Deflation

With the latest CPI numbers stoking interest in the “transitory” vs. “not-so-transitory” inflation debate, it’s perhaps fitting that the latest MacroVoices interview featured Macquarie global equities strategist Viktor Shvets, who explained why he believes the world is entering a new era where the deflationary pressures produced by technology-induced improvements in productivity will create a “race to zero” that will see prices continue to fall.

However, Shvets believes that over the next 10 to 20 years, inflation and deflation will act more like opposite sides of a pendulum that occasionally swings back and forth.

On the inflationary side, one new development is the dominance of fiscal policy over monetary policy in terms of their impact on the market. An innovation inspired by COVID-19 that Shvetz expects will increasingly become the norm in the US. As the younger generation embraces “socialism”, the US government will likely increasingly pay for medicine and even a universal basic income for those who don’t work (and perhaps even for those who do).

Just this week, the Biden Administration introduced new handouts for families with young children.

And the third element is a deglobalization and localization that’s going to continue to strengthen. So what you have in the next 10 to 20 years, two very powerful forces are going to struggle. One is very strong, long term disinflationary force, which ultimately is going to win. And the other one is more inflation created from various things we’re going to do over the next 10 to 20 years. Now, the interesting question, Erik is who is going to decide whether inflation or disinflation wins at any given point in time? Now, my personal view for quite some time has been that private sector will never walk again on this system.

While Shvetz doesn’t believe in systematic inflation, he believes in systematic disinflation.

The reason is that technology has turbocharged the spirit of competition. And the same deflationary forces that gave us free music, free equity trades and free digital news will soon get to work on other aspects of the economy, until prices are falling on nearly all goods and services.

So if one agrees with me, that cost of capital must fall forever, then it’s like pouring a kerosene on a bonfire of technological age. And what technology does incredibly well is reducing marginal pricing power of both labor and capital, and corporates, and brands. And so what happens over time, those reduction in marginal pricing power converges into average pricing power, which also declines. And eventually, almost everything becomes free. There is no prices, just like information today is almost entirely free. Just like publications today, almost entirely free, just like trading on the New York Stock Exchange quite, not quite, but almost entirely free. Just like a lot of music is almost entirely free. So we already have massively reduced marginal pricing power in a lot of industries. We’ve already reduced marginal pricing power of labor.

Shvetz even cited research from McKinsey and others to justify his “everything goes to zero” thesis about long-term price deflation.

That’s why McKinsey in their review, was estimating that the impact of information age could be 3000 times the impact of industrial age. In other words, much broader and much faster, 300 times broader, 10 times faster. And so when I say everything goes to zero, eventually, the productivity growth rates will be so high, that there will be no need to value any of that stuff. And the economists are not going to function the same way as I’ve done over the last two or 300 years.

Moving on to a discussion of contemporary markets, Townsend asked Shvetz for his view on interest rates. Is the only rational direction for Treasury yields higher? To this, Shvetz offered a detail answer grounded in history. As government debt burdens have soared, the only way forward for central banks is to follow the BoJ and artificially repress yields as central banks buy up the entire market.

Well, it reminds me what people were saying about Japan. Remember in 1990s and early 2000. The view was that if God forbid Japan ever ignites inflation, they immediately go bankrupt because the government will be spending 50, 60, 70% of their budget just servicing the debt. Now, how much do you think Japanese Government today is spending on servicing debt 4%. Not 50, not 40, not 80, 4%. And the debt burden is much, much larger than what it used to be. Now a lot of people say, well, you know, Japan is unique.

Okay, let’s look at Eurozone. How unique is Eurozone? Look at the UK? How unique is the United Kingdom? And if you think of the US. One of the things that is becoming very clear, is that what happened in Japan since early 90s. What happened in Eurozone since global financial crisis over the last five or six years started to happen in the US as well. And a basic sort of signal that the US is sending now, just like the other economies do, it’s not about supply of money. It’s about demand for money. It’s not about supply of credit.

It’s about demand for credit. And increasingly, the more we leverage, the more we financialize, the more we erode marginal demand for credit. Now, what that implies is that interest rates not only they cannot go up, but they will not go up. And by the way, if they do, remember, we always have perpetuals, which have no value at all, because they’re never redeemable.

On the horizon, we have MMT or modern monetary theory. We already have BoJ. Remember the has been monetizing more debt that the Government of Japan has been issuing. That’s why they’re sitting on 50 to 53% of JGB market. Eventually, you don’t need the JGB market at some point in time.

Echoing a point made by Jeffrey Gundlach, Shvetz points to the fact that on top of its burgeoning debt, the US also has hundreds of billions of dollars in unfunded liabilities.

Readers can listen to the entire interview below courtesy of MacroVoices:

Tyler Durden

Thu, 07/15/2021 – 21:40

Read More