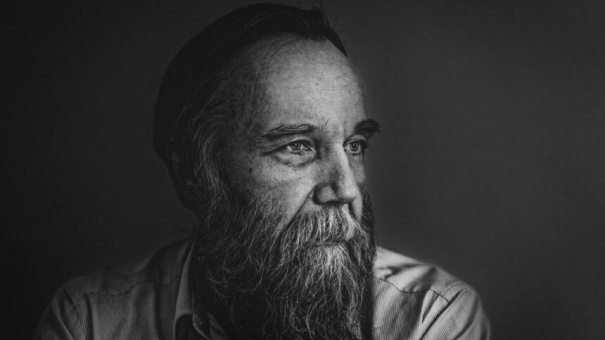

Russian philosopher, mystic, political strategist, radical bohemian, and geopolitical guru; Aleksandr Dugin is notorious, yet few in the West know much about him. Described by some as the brain of Russian President Vladimir Putin, Dugin is often depicted by Western media as a Rasputinesque figure with a dangerously eerie grip over Russia’s political and intellectual elite.

While it may be true, as countless articles assert, that Dugin has a lot to do with Russia’s current geopolitical strategy in Ukraine, less explored are the religious and spiritual beliefs embedded in his philosophy. These are informed on the one hand by perennialism and the esoteric traditionalism of the French intellectual René Guénon, which attempt to synthesize Eastern metaphysics with Western philosophy, and on the other hand, by Russian Orthodox Christianity.

While it may be true, as countless articles assert, that Dugin has a lot to do with Russia’s current geopolitical strategy in Ukraine, less explored are the religious and spiritual beliefs embedded in his philosophy. These are informed on the one hand by perennialism and the esoteric traditionalism of the French intellectual René Guénon, which attempt to synthesize Eastern metaphysics with Western philosophy, and on the other hand, by Russian Orthodox Christianity.

Dugin’s political philosophy is aimed at the creation of a multipolar world in which the U.S. is no longer the world’s sole superpower. He also envisions a “fourth political theory” that will be neither capitalist, communist, or fascist, but an entirely new compilation adopting the good facets from all three systems. But unlike most political theorists, his beliefs are imbued with occult and mystical hermeneutics. Those who do not get a grip with his spiritual beliefs will be doomed to a shallow and soulless understanding of his influence.

I interviewed Dugin in February—several weeks before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—and asked him to explain his Christianity and how it has influenced his philosophy. It’s a topic that interests him greatly, and his response reflected the intensity of his interest.

Dugin told me that his path to Christianity came in three important stages. The first was his baptism as a child on the behest of his great grandmother. But he did not pay much heed to the faith while growing up under the influence of a communist society and an atheistic father.

The second stage came at the age of 18, when he fell into a circle of underground Russian radicals who were intent upon rejecting the utopian maxims and mythos of communism. They introduced the young Dugin to the alien world of esoteric traditionalism through Guénon (1886–1951) and Julius Evola (1898–1974); he said their teachings filled his spiritual void. Esoteric traditionalism advocates that all civilizations and peoples should return to the spiritualism of their traditional cultural archetypes—Russians being natural Orthodox Christians, for example. For Dugin, Guénon and Evola gave him the foundation from which he began to critique modernity and look deeply into Russian Orthodox Christianity.

Dugin said that during the late Soviet period and in the first five years of the 1990s, he could not bring himself to reconcile “true tradition with intellectual Christianity” and that he was discouraged by the outlook of contemporary Christian believers. Eventually, he humbled himself into accepting Orthodoxy, submitting himself to its religious discipline in order to gain access to the sacraments.

This submission ultimately led to the third stage; he joined a small branch of the Russian Orthodox Church, which, while still in communion with the Moscow Patriarch, practiced the old rite of the pre-Nikon reforms. The old rite appealed to his appetite for tradition, and is somewhat similar to how a remnant of Catholic traditionalists prefer the pre-Vatican II liturgy, disciplines, and sacraments. Dugin made it clear to me that he felt a great similarity between his return to the Church and that of the American Guénonian traditionalist and Orthodox priest, Seraphim Rose (1934–1982), who was baptized as a Methodist and converted from atheism.

Dugin explained that he chose Orthodox Christianity over Catholicism and Protestantism because he sees the Orthodox Church as imbedded into the mythos of Russia and as part of a tradition from which he cannot detach himself. This response led to a trickier question: how does he reconcile the dogmatic absolutism of Christianity with the open approach toward Eastern religions taken by esoteric traditionalism, which could be seen as indifferentism to the Orthodox mind?

Dugin responded that Evola and Guénon taught him to respect different sacred religions and not to compare differences between them, but instead to compare them against modernity. Everything anti-modern is good, Dugin said; seeing different religious traditions in union with this principle allows him to reconcile non-Christian and non-Orthodox traditions. He admits rather paradoxically, however, to the belief that one must fully assent to the teachings of one’s Christian religion, including its emphasis that all other faiths are in error. Dugin indicated that he gets around this difficult problem by finding ecumenical commonality. He stated that, for instance, if a Catholic fully lives his religious tradition, then it is possible to find commonality with other traditional religions in a mutual opposition to modernity.

Everything anti-modern is good, Dugin said; seeing different religious traditions in union with this principle allows him to reconcile non-Christian and non-Orthodox traditions.

Dugin said his approach to promulgating his philosophy of anti-liberalism and Eurasianism is not as focused on Christianity as his other ideas. His aim has always been to create a philosophical language that is universally adaptable to all religions, cultures, and peoples irrespective of their religious beliefs. To do this, he appeals to Guénon’s idea of a communal fight against the modern world.

In Dugin’s view, Christianity is a sacred religion among many existing in what he calls “a historically eschatological, and apocalyptic time’’ and should therefore not be fighting against other religions but against modernity. All forces must be used “to fight against the eschatological modern Western reality,’’ which he said is not only anti-Christian but also, at its roots, against the Western tradition (i.e. against itself), and therefore threatens all religious paradigms.

Having allowed Dugin to make it clear that he takes a broad and ecumenical approach, I would argue that he actually places more emphasis on Christianity and its role in fighting Western modernity than he likes, for pragmatic reasons, to publicly state. Dugin relies strongly on the Christian view of the Apocalypse and believes we are living in the age of the Antichrist. This view is essentially Christian and is why Dugin strongly expresses the idea that Christians should fight Western modernity. It is important to mention here that he sees the enemy as Western modernity, not the West itself, and that Christianity will play a major role in defeating that enemy.

Then the Western Church became more individualistic and prepared a path for liberalism. According to some, such as Alain de Benoist, Christianity through an inherent defect in its conception of the individual salvation of the soul introduced the danger of individualism into Western thought. Dugin is careful here to emphasize his disagreement with this view. Despite its emphasis upon individual salvation, “Christianity did not destroy the communal spirit” as seen in the Eastern Orthodox Church, Dugin said. Rather than a creation of Christianity, liberalism is its perversion.

The descent of the Western Roman Church into liberalism followed the pattern of the promotion of nominalism by William of Ockham and the Franciscan monks in the late Middle Ages, which pattern Dugin said created a “proto-liberal anthropology, and proto-liberal society’’ culminating in its apogee, Protestantism. This Protestantism and its work ethic led to capitalism, as described by Max Weber in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1903), and to what Dugin called the creation of “a totally secular and hedonistic society.” This society in Dugin’s view has destroyed religion, ushered in a pure state of post-cultural degenerations, and is becoming a post-human technological world.

It was at this point that I suggested to him a reason for optimism: from a reproductive and demographic perspective, it appears that secularism may eventually wane as religious families have more children than do atheists. Dugin dismissed my optimism, however, calling it an example of Anglo-Saxon false hope that greater numbers by themselves will solve spiritual problems. Christians, he argued, should be focused instead on saving souls.

Dugin believes that Westerners in particular have an obligation to fight the force of the Antichrist—modernity—since it was the West that created modernity. He describes this fight as a spiritual war in which “we must not sell our souls to the Antichrist’’ but be willing to “fight until the end and to die to win with Christ.”

The willingness to fight modernity is more important than the likelihood of victory, Dugin said. God “approves of us” and will save those who are tested in spiritual battle. This fight must be directed towards what Guénon called the “Kingdom of Quantity,” which Dugin said manifests itself today as “liberalism, LGBT culture, artificial intelligence, banks, and capitalism.”

Dugin’s dramatic religious statements certainly evoke millenarian ideas. In my opinion, however, they are the clearest examples of the power of the Christian faith that animates his radical political and spiritual philosophy.

Victory in this spiritual battle against modernity would lead the way to Dugin’s “fourth political theory,” which would supplant the three political systems of modernity: fascism, communism, and liberal democracy. The fourth theory would deconstruct each of these systems into only their positive elements, combinations of which would be moulded according to the traditions of each civilization. Politics in this system would be neither focused on individual materialism, class struggle, or nationalism, but rather what German philosopher Martin Heidegger called Dasein, or being in its particularity.

Because the United States controls overwhelming force in the world we live in a unipolar world. Dugin believes this hegemony must be broken up to allow different “poles” of world civilization. Examples would include the Islamic, Eurasian (Russian), and Chinese poles, with each embodying their own civilizational tradition. This multipolarity is an alternative to globalism; its will allow sociological diversity and end political absolutism in favour of cultural relativism.

Malofeev’s letter demonstrates how Russians like Dugin view the conflict in Ukraine: as a holy war that will purge modernity from the Eurasian sphere and end what Guénon described as the Kali Yuga—the Hindu concept for a decadent age of strife and sin. It is this deep religious and spiritual motivation behind Russia’s campaign in Ukraine that has been dangerously overlooked by Western analysts and has forced them to misunderstand Russian motives.

To the extent that Dugin does influence Putin and other Russian leaders, that influence is deeply religious and frames events as a battle between the ideologies of modernity and traditionalism. The conclusion of this conflict will without a doubt have unimaginable consequences upon religion, culture, and geopolitics for years to come. Dugin’s philosophy is making its mark on the world, right before our eyes.

Edward Stawiarski is an independent researcher and archival analyst who writes from London.