You won’t find this story anywhere else for Black History Month, but you should! By the mid-1900’s, a “Buffalo Soldier” named David Fagen was virtually a household name, particularly in the African American community. Fagen’s story makes myth of the false contention that African Americans offered little resistance to institutionalized racism from the Civil War until the end of WWII.

Was Fagen a hero or “a mad dog”? The answer is rooted in whether you believe that fighting against U.S. colonialism/imperialism in 1899, in this case the U.S. war of Philippine conquest, is righteous and worthy of giving rise to a true hero, martyr and courageous Buffalo Soldier, who deserted the U.S. side and joined the Philippine Revolutionary Army. The PRA was fighting to establish their own independent republic after the Spanish were kicked out.

In diaries and letters, Black soldiers posted in the Philippines. recounted how racism was endemic in the U.S. military, describing the racist abuses suffered by both African Americans and Filipinos.

Fagen was a native of Tampa, Florida, the youngest of 6 children of former slaves. He grew up where Jim Crow racial segregation laws prevailed. With the specter of lynching, race riots and the chain gang looming over Tampa’s Blacks, Fagen “lived in dread at all times.” Searching for any escape from Jim Crow, Fagen enlisted in 1898, being assigned to the 24th Infantry Regiment, a unit of so-called Buffalo Soldiers.

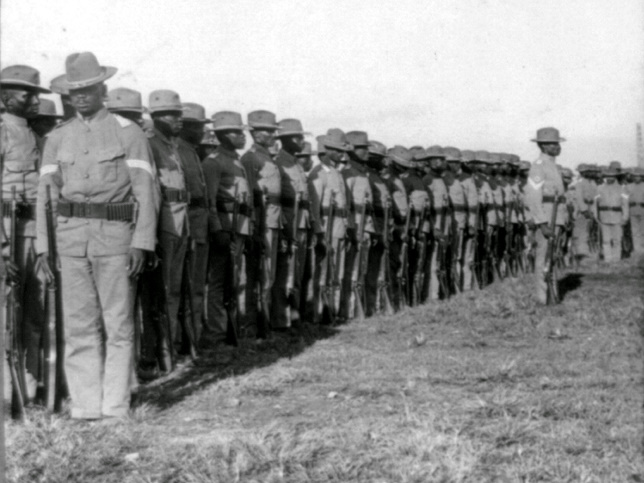

Expansionist USA, intent on developing a global commercial empire, dispatched 6000 African American soldiers, including 2100 of the famed Buffalo Soldiers, to the Philippines islands per President McKinley’s assessment that the racial inferiority of Filipinos justified denying them sovereignty and engaging in a bloody war of conquest. Fagen, now on the battlefield, detested his white commanding officer Lt. Moss, a West Point graduate. Moss and Fagen clashed repeatedly, with Moss eventually fining Fagen more than a month’s pay and sentencing him to 30 days of hard labor. Life was immutably altered when Fagen, after just a few months of battling Filipino rebels, turned his back on the U.S. army and joined Filipino revolutionaries who were actually fighting against American invaders.

At the time, there was a fierce debate in African American communities on their role in these foreign wars. Many saw the invasion of the Philippines as a ‘race war’, through which white settlers would inevitably repeat in Asia the wave of enslavement and genocide that had been inflicted on Native Americans and Black slaves. Contrary to enlistment promises, African American soldiers in the Philippines were relegated to second-class status. Officers often ordered them to carry out ‘dirty jobs’ that no white soldiers wanted to do. They were also forced to serve as expendable “shock” troops on the frontlines, where lives were most at risk, while white commanders stayed back at a safe distance from the Filipino rebels. Filipino insurgents put up posters and distributed flyers with messages encouraging ‘colored’ soldiers to join their cause, appealing to their common suffering at the hands of white Americans.

Historians studying the Philippine-American War estimate that at as many as 15 Buffalo Soldiers decided that their place, rather than helping to suppress the Filipinos’ struggle for independence, was in joining them in revolution. The supposed ‘deserters’ of the 24th infantry proved one thing: systemic racism and oppression by white Americans was enough to forge alliances across vast national and ethnic lines.

This may have been the very reason Fagen turned his back on the U.S. army, for a new life as a Filipino guerrilla. One night, Corporal Fagen snuck out of his barracks and met with a Philippine ‘insurrecto’ officer, who had arranged Fagen’s escape. The rebel agent had a horse waiting for Fagen outside the garrison, and together, they disappeared into the jungles.

Fagen was never captured or killed. Out of respect and tribute for his role as guerrilla leader, his Filipino compatriots addressed him as El General, although he was a Captain. Despite the wide respect and honor in which he was held by his fellow anti-imperialist insurgents, the U.S. army branded Fagen a deserter and traitor and expunged all memory of him from the annals of history. His racist white U.S. General, Frederick Funston, described Fagen as a “bandit pure and simple, and entitled to the same treatment as a mad dog”.

In this writer’s estimation, Fagen was anything but a ‘mad dog’, but a courageous resistance fighter who chose the right side in a battle against U.S. aggression and imperialism. I conclude with the aspirational belief, circulated by many, that Fagen fell in love with a Filipina woman and ran away to the mountains to live a peaceful life with her.

Long live the memory of David Fagen.