The Group of Seven (G7) has come a long way since its inception in the mid-1970s at the initiative of then-French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and West German chancellor Helmut Schmidt to discuss the world economy and consult on an international economic policy following the first oil shock and the collapse of the Bretton Woods fixed-exchange-rate system.

But by the 1980s, the G7 had begun embracing foreign and security policy issues. The apogee of the G7 as the high table on international security was probably reached in 1991 when the group invited Mikhail Gorbachev to talks in London, parallel to the G7 summit. In 1998, Russia was formally admitted to the group, making it the G8.

For the next decade and a half, Russia started regularly attending the summits until 2013 when a parting of ways followed the “color revolution” in Ukraine, and the G8 reverted to G7. Since then it has behaved unabashedly as an exclusive Western club.

This much recap is useful and necessary to recall how this intensely political platform of seven Western countries came to nurture such notions of exceptionalism. But now, facing a world in transition, they are apprehensive that the world of yesterday is drifting away.

In a dramatic role reversal since the 1970s, the developing world now accounts for almost two-thirds of the global economy compared with one-third by the West. Of course, this reality, which surged during the 2008 financial crisis, in turn led to the birth of the more representative G20, but the G7 refuses to retrench.

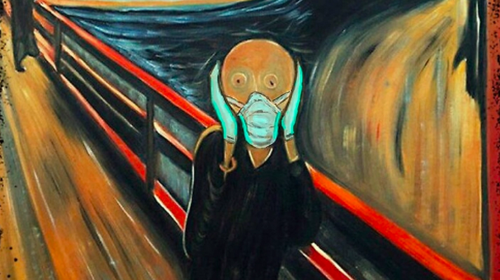

The Covid-19 pandemic may be exacerbating this historic shift. Overall, the Western powers are in a state of trauma as they look around and sense that the sort of dominance they enjoyed as overlords by virtue of their grip on the world economy is no longer feasible.

By any reckoning, the G7 leaders who gathered in Britain for the summit, which concluded on Sunday, were conscious of the undercurrents swirling around them.

A change of direction?

The G7 is under compulsion to reinvent itself. The weekend summit marked the first step toward reframing the G7 as the fountainhead of the democratic world, enabling it to lead a coalition of the willing in a global campaign against China.

However, there are signs of disunity among the G7 countries in regard to an anti-China crusade. China is a driver of growth for the world economy and has even reconfigured some of the Western economies.

Herein lies the paradox. One of the outcomes of the latest G7 summit is supposedly a Western countermove “to address the infrastructure financing gap” by mobilizing private-sector capital and expertise. But where does the G7 money come from?

Their economies are mired in debt. And why should their private-sector companies borrow unless there are commensurate returns and, most importantly, do they have the wherewithal, expertise and relevant experience to undertake the kind of projects that Chinese companies are undertaking in Africa or Asia within the ambit of the Belt and Road Initiative?

According to data provider Refinitiv, by the first quarter of 2020, the value of China’s Belt and Road projects already exceeded US$4 trillion. These are hard realities.

In geopolitical terms, the main outcome of the G7 summit is that the European participants could heave a sigh of relief that a new tone has appeared hinting at interest on the part of Washington to begin to repair the breaches inherited from four years of Donald J Trump.

President Emmanuel Macron of France said after meeting Trump’s successor Joe Biden: “It is great to have a US president who’s part of the club and very willing to cooperate.’’ Surely, the friendly ambiance has helped Biden to inject a certain Cold War overtone to the G7 proceedings.

Looking ahead, however, the G7’s predicament is going to be threefold. First, in reality, this is a charade, like Don Quixote in the Cervantes novel tilting at the windmill in delusional enchantment; for China and Russia are not only anywhere near forming their own adversarial bloc to challenge the West, but are not even planning to move in such a direction.

No military alliance

Last week, in an interview with the Communist Party of China Central Committee newspaper Global Times, Russia’s ambassador to Beijing Andrey Denisov said in the shadow of the G7 summit and the upcoming summit between Vladimir Putin and Joe Biden:

“Russia’s position is clearly much closer to China’s [than to the United States’]. In recent years, the US has imposed sanctions both on Russia and China. Although the areas and content of the US dissatisfaction towards Russia and China are different, the goal of the US is the same: to crush the competitor. We clearly cannot accept such an attitude from the US. We hope that the Russia-China-US ‘tripod’ will keep balance.

“Russia and China are both world powers and have their own interests at the global and regional levels. These interests cannot be identical in all cases. But on the whole, the international interests of Russia and China are the same, so our positions on most international issues are the same.

“The most obvious example is how we vote in the United Nations Security Council: Russia and China often cast the same vote at the Security Council … In fact, our positions on some of the most important issues are the same, and we just have different views on some specific details.”

Does the above statement add up to a military alliance or even shared ideology between Russia and China? Clearly, not so.

That brings us to the second point, namely, the US will be hard-pressed to align the Western partners with its foreign-policy rivalries vis-à-vis China that are in essence borne out of its sense of frustration that its century of global dominance is under serious challenge and has nothing to do with China undermining Western interests.

Without doubt, the G7 has brought to the fore that there is sharp disagreement among the United States and its allies about how to respond to China’s rising power. Europe – especially the two major European powers Germany and France – do not see eye to eye with the US as to whether to regard China as a partner, competitor, adversary or outright security threat.

This mood swing will stall the US efforts to muster a comprehensive Western response. In the near term, the litmus test will be whether the Biden administration can persuade America’s allies to denounce China’s use of forced labor and take concrete downstream actions to ensure that global supply chains are free from the use of Chinese labor – or else, all this becomes bark with no bite.

EU walks a fine line

At the end of the day, the laws of economics are stronger than geopolitical constructs or human-rights concerns.

Significantly, on June 8, the president of the European Council, Charles Michel, defended the European Union’s efforts to negotiate a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China by calling the investment deal “a huge step in the right direction.” He told reporters, “For the first time we are making a step to facilitate investment by European companies” in the Chinese economy.

The timing of the remark was rather delicate and intriguing, even as Biden was taking off for his European tour. It signified that as much as China-EU economic ties are in a complicated transitional phase, that’s not an excuse for the US to put its finger in the pie.

More importantly, it underlines that neither the EU nor China wants to see US interference making things worse and less predictable. On the other hand, of course, the Europeans wouldn’t like to lose their policy independence and become a pawn in the US containment against China.

This is only to be expected, as in 2020 China overtook the US as the EU’s largest trading partner. The value of trade in goods and services between China and European countries reached nearly $1 trillion, with two-way cumulative investments exceeding $250 billion.

A survey released recently by the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China showed that nearly 60% of European companies plan to expand their businesses in China this year, an increase of nearly 10 percentage points from the 51% surveyed last year.

Suffice to say, Europeans are savvy enough to know that politicization of China-EU economic ties will be detrimental to their long-term interests.

This article was produced in partnership by Indian Punchline and Globetrotter, which provided it to Asia Times.

M K Bhadrakumar is a former Indian diplomat.