Gasflation

By Ryan Fitzmaurice, Senior Commodity Strategist, Elwin de Groot, Head of Macro Strategy and Hugo Erken, Head RR Economic Scenarios & Projections at Rabobank

“Everything is energy and that’s all there is to it. Match the frequency of the reality you want and you cannot help but get that reality […]” — Albert Einstein

“Jumpin’ Jack Flash, it’s a gas, gas, gas” — Rolling Stones

Summary

US and European natural gas prices have jumped to multi-year highs; to the extent that comparisons with the 1970’s oil crises are perhaps not as far-fetched as some would think

In this piece we look at the causes behind this development and explain that structural shifts in the market probably better fit the story than the “just a market fad” explanation

Various other markets – outside energy – such as fertilizers and ethanol production could be affected by structurally higher gas prices, adding to the host of supply-chain disruptions that businesses are dealing with

Moreover, if sustained – and this is obviously very weather/geopolitics-dependent – US and particularly European households could be in a for an expensive winter, as inventory levels are at multi-year lows

More than in the past, governments may be keen to soften the blow to households, although this would obviously have implications for budgets

Introduction

Commodity markets have been in the spotlight for much of this year and even more so recently, as tight fundamental balances, hurricane supply disruptions, and widespread inflation worries propel prices higher across sectors. Commodity gains have been broad-based in nature, with all sectors gaining this year except for precious metals.

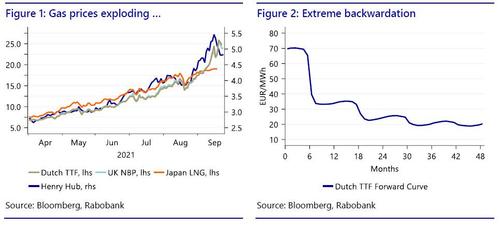

That said, it has really been the energy sector and specifically natural gas markets that have witnessed the most explosive price rises. Natural gas prices in Europe and Asia have gone parabolic, increasing by well over 200% in Europe and 150% in Asia in a matter of months. This compares to gains of nearly 100% for US benchmark prices. So, what’s behind these abrupt and staggering price increases?

A ‘fad’ or something that was long in the making?

Looking at the big picture, the recent move in global natural gas prices is a long time in the making, and structurally higher natural gas prices are likely here to stay. The main driver is a big slowdown in natural gas production in the US, the global growth engine for such supplies over the past decade via the fracking revolution. In fact, the US was practically swimming in natural gas up until a few years ago, when LNG export capacity began to increase.

Things have changed rather dramatically in recent months, however, and the US is no longer growing supplies, with production remaining well off the pre-pandemic highs. At the same time, global demand continues to move higher as the world attempts to shift towards a zero-carbon future (As the EU has reduced the supply of emissions credit, the EU’s benchmark carbon price rose above EUR 60 per metric ton in early September for the first time in its existence. According to EEX data, by 20 September, 437 million ton of CO2 was auctioned in 2021, compared to 459 million tons in the same period last year.) As it stands, this ambitious goal is simply unworkable without natural gas providing an important bridge away from the dirtiest of fuels such as coal and fuel oil. As such, global natural gas supply and demand balances are extremely tight and storage levels are critically low heading into the high-demand winter months.

Further to that end, our fundamental modelling is indicating that global storage facilities would be practically empty in a cold winter scenario. This would be a catastrophic scenario which the market is trying to solve for now by increasing prices so much that demand is forced to ration. We are beginning to see this dynamic play out in real-time, as fertilizer and other industrial facilities are forced to shut in Europe as a direct result of the high natural gas prices. This should help ease demand on the margin – with major side-effects, as in the threat of food shortages in the UK due to a lack but so far, no supply-side relief is in sight.

Less wind and more geopolitics

Next to the structural factors highlighted above, a confluence of – mostly transitory – factors has aggravated the shortages and hence near-term pressures on spot prices. This has caused extreme backwardation in the forward curve for gas (see figure 2) for the Dutch TTF benchmark. An unseasonably cold winter followed by low wind generation on the European continent has contributed to rising demand for gas, thus slowing down the build-up of inventories. In addition, global demand for gas was propped up by a particularly hot Summer in certain areas of the World: Southern Europe, the US and certain parts of Asia. This sparked peak demand for electricity for A/C units. All these factors together have been hampering the build-up of gas inventories.

Further to this, the supply of Russian gas has slowed down. Some observers argue this is because the administration in Moscow is trying to put pressure on the German government to hasten the certification of the new Nord Stream 2 (NS2) gas pipeline between Russia and Germany. Although work on the pipeline was recently completed, the German regulator has said it would take up to four months to complete the certification process. The pipeline is the at the center of geopolitical tensions, as both the US and Ukraine argue that it allows Russia to circumvent the Ukrainian pipeline – threatening its security. Moreover, the US is concerned the pipeline would raise Europe’s reliance on Russian gas – which it obviously does. That Gazprom and the Kremlin have said gas sales can be ramped up after the approval lends support to the view that the gas deliveries are being used as a tool to put pressure on the process. Earlier this week, the IEA threw its weight in the discussion, saying that Russia “[…] could do more to increase gas availability to Europe […].”

Aside from the question whether Russia would be able to ramp up production at short notice (and in such a way that total deliveries through both pipelines would significantly outstrip normal deliveries), concerns over future supplies are not entirely without merit. The duration of the certification period, with a decision then falling right in the midst of the European winter, is clearly one aspect that doesn’t help.

We also know that several other EU countries, such as Poland, are very unhappy with the increased reliance on Russian gas. Moreover, in late August, a German court ruled that NS2 is not exempt from the EU competition rules, which implies that the operating company must unbundle its business, as pipeline owners and suppliers cannot be the same. Meanwhile, a (big) victory for the German Greens in the upcoming elections could be a further complicating factor. Their leader, Annalena Baerbock, has been advocating a hard line vis-à-vis Russia. This, in turn, also adds to the risk that Russia may first up the ante in this geopolitical chess game.

One can meanwhile posit that perhaps Moscow would not be entirely unhappy to see further division and economic weakness in Europe, especially if that is a precursor to it still ending up with a dominant position in EU energy supplies.

Amongst the geopolitical turmoil, Norway has stepped in by allowing state-owned Equinor to export an additional 2 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas from the 1st of October onwards. Still, one can question whether this additional amount is meaningful to alleviate of Europe’s gas woes, as the net average import of natural gas on a quarterly basis in Europe amounts to more than 100 bcm.

Other markets may be affected as well

The supply-chain disruptions that the world has witnessed since Covid, in sectors such as semiconductor manufacturing, now has its own equivalent in the natural gas crisis. First of all, electricity providers are being hit hard, especially if they have not sufficiently hedged their purchases. This already appears to be a reality in the UK.

BEYOND PETROLEUM: A rather unscientific survey, but just visited 5 BP stations in West London, and all but one were dry (and the one that still had some availability had only gasoline but no diesel). Officially, BP says 30% of its network has no fuel #OOTT https://t.co/p1zuyujtgf pic.twitter.com/5WLsv55fAG

— Javier Blas (@JavierBlas) September 26, 2021

Yet the gas shortage also highlights the dependency of other (energy) markets to gas, and those that rely heavily on electricity – which is a very long list.

Clear examples are the production of ethanol, which requires a lot of heating (by natural gas) to distilled alcohol. And the list goes on and on: aluminum production, (specialized) chemicals such as paint, refined products, plastics and food packaging.

Almost the entire economy is involved one way or another in a cascading effect – just as we have seen in other areas of seemingly-innocuous supply chain disruption.

Fertilizer production is a prime example that shows the complicated nature of current-day supply-chains. Modern fertilizer plants use natural gas to make ammonia by adding nitrogen (from the air). Several big fertilizer producers have already been forced to cut back production. But the impact doesn’t stop there, because carbon-dioxide (CO2) is a key by-product in modern fertilizer plants. This food-grade CO2 is then used to stun animals for slaughter in the meat industry and for injection in packaging to extend shelf-life. So, natural gas shortages may even turn into meat shortages, as the British Meat Processors Association (BMPA) has warned.

The key point here is that even if the gas shortages are overcome, the impact will continue to reverberate through the various markets that depend on gas, potentially creating new hiccups and headaches in other chains.

Recipe for old-fashioned supply-shock recession?

It is important to note is that the recent increase in gas prices comes on top of a broad-based rise in commodities that started with a sharp reversal of the early oil price declines of 2020, and which then spread out to a much broader spectrum due to weather conditions, a quicker-than-expected re-opening of economies, and ensuing bullwhip effects (as we explain here).

This obviously raises the question whether this development is a recipe for a supply-shock recession or, at least, a slowdown in demand. Although one could argue that a rise in (relative) prices for commodities simply constitutes a wealth transfer from commodity importers to commodity exporters (and from ‘users’ or consumers to producers), the speed and extent of these transfers often leads to many second-order effects, with a slowdown in demand as a by-product:

Commodity producers/exporters may not spend all of their ‘windfall’ profits immediately, so global aggregate saving increases;

The price volatility leads to uncertainty causing lower investment;

‘Middleman’ in the chain may either win or lose, depending on their position (see electricity sellers or fertilizer producers), and some of the losers may actually go out of business; and End-consumer, i.e. households, will experience a rise in prices which is unlikely to be offset by higher wages in the near-term. In other words, they see their real spending power reduced. This, in turn, may lead to a decline in confidence, changes in spending patterns and even a decline in the aggregate volume of consumption.

The 1973/74 and 1979/80 oil crises are key examples of supply shock (reduced supply at higher prices) recessions, but figure 6 shows the majority of EU recessions since the 1970s were preceded (by about 6-18 months) by a sharp rise in commodity prices.

Moreover – to put the current rise in gas prices in perspective – we have plotted its trajectory since end-2019 against the oil price development during the two major oil crises in figure 7. By these measures, the near-term price shock already exceeds those infamous 1970’s episodes!

In the next below, we look at a simulation with our NiGEM model to gauge the impact of the gas price shock on economic growth:

Macro-economic impact of gas price shock

The gas price shock potentially has some significant adverse effect on the Eurozone economy in the recovery phase from the Covid-19 crisis. If we assume the higher gas prices will result in a 1ppts higher inflation rate in the Eurozone2, distributed over H2 of 2021 and 2022, this could go at the expense of private investment in the Euro Area by 3.5ppts (figure 8).

Companies in different branches and industries are already struggling with the costs of higher commodity prices. But there is a knock-on effect on business investment against the backdrop of energy shortages, as some areas in the Eurozone will move dangerously close to the maximum energy capacity. As a consequence, for example, some companies will be refused the proper licenses to expand or start operations in a certain area. This is, for instance, already the case in the Dutch province of North-Holland (see this article in Dutch).

Although we expect an ongoing recovery of the Eurozone and the Dutch economy in 2022 (of 3.9% and 3.5% respectively), the current gas crisis might shave off 0.7ppts of growth according to our calculations.

What does it mean for inflation?

In order to gauge the inflationary impact of the recent rise in gas prices – whose impact is being particularly felt in Europe – we zoom in on the Eurozone and then further onto the Netherlands. The UK is, to some extent, a special case and so we refer the reader to the box below this paragraph.

If gas prices prove sticky, how much additional inflation would this lead to? For the Eurozone, we need to emphasize that a considerable amount of energy price inflation has already materialized, and that our baseline projections assumed a further increase in energy prices into 2021.

Our baseline Eurozone inflation projections for 2021 and 2022 were 2.2% and 1.8% respectively. However, when we take the recent gas price hike in the market as a separate ‘shock’, we estimate that it could roughly add 0.15ppts to our inflation estimate for 2021 and another 0.25ppts for 2022.

We still feel that these estimates are somewhat conservative, as we do not take into account any knock-on effects on prices of other energy sources and/or products based on gas. Moreover, we should also bear in mind that the impact may not be the same across all countries, as it depends on the amount and speed with which higher gas prices feed into electricity prices and the composition of these items in consumer spending baskets (see figure 10).

We used the Dutch 1m and 1y forward benchmark gas contract as instruments and assumed both would stay at around their present level (c. EUR 70/MWh and EUR 40/MWh) for the remainder of 2021 and 2022. Figure 9 shows the additional contribution from higher gas prices to the electricity and gas component in the Eurozone HICP (which has a weight of around 6%).

The Netherlands

The Netherlands has an abundancy in natural gas and consequently has been a net exporter of the commodity for decades. The Groningen gas field, discovered in 1959, has provided a steady revenue stream for the Dutch economy and the Treasury. However, drilling for gas in Groningen has also caused earthquakes in the northern part of the Netherlands, which have increased in intensity and frequency over the last couple of years. Inevitably, the government decided to scale back on the extraction of gas in Groningen, which will reach a full stop in 2022. Consequently, the Dutch gas supply is increasingly dependent on import from abroad (Figure 11). Moreover, being pretty much autarkic in the supply of natural gas, the entire energy infrastructural revolves around the use of natural gas. This explains why the pass-through of gas prices to consumer prices is higher in the Netherlands (24%) compared to the Eurozone (17%). The combination of the two, i.e. higher dependency on foreign supply and energy infra that hinges on the use of gas, makes the Dutch economy vulnerable to a fluctuation in gas prices.

To assess the potential impact of higher gas prices on the additional energy costs that consumers might face, we use the Dutch 1y forward benchmark gas contract as an instrument and assume it stays at current levels of approximately EUR 40/MWh for the remainder of 2021 and 2022. As the weight of the energy component within total the Dutch consumer basket is 4.3% (with gas expenses making up for 2.9%), a full pass-through of higher gas prices could prop up inflation by 0.3ppts in 2021 and a staggering 1.3ppts in 2021 (see Figure 12).

The average Dutch household currently spends approximately 1,600 euros on energy (of which 1,000 on gas). This means that – in a full pass-through scenario – the current gas prices would raise the energy bill by roughly 600 euros for each household. This is a bleak perspective, given that it will most likely hit low income households, which are also the ones with highest propensity to consume. Indeed, very recent research (in Dutch) shows that 7% of all Dutch households are coping with so-called ‘energy poverty’: high energy expenses, a low income and poorly insulated houses. Moreover, the same research shows that half of all Dutch households live in houses with bad or mediocre insulation standards, but are unable to improve their situation, either because it concerns rental houses or because people simply do not have the money.

That said, we feel that the ‘full pass-through’ scenario is unrealistic, since the Netherlands is able to mitigate any adverse prices effects by relying increasingly on its own supply. Indeed, half of total gas needs in the Netherlands is currently met by domestic sources. In a mitigation scenario, inflation would end up being 0.2ppts higher in 2021 and 0.5ppts higher in 2022 (figure 12); which might still result in a significant jump in households’ energy bills. During the 2022 Budget Debate this week, the Dutch caretaker govt. has announced to allocate EUR 500 million to mitigate the impact of a rising energy bill for households. This is supposed to be realised by lowering the taxes on energy.

Going forward, the most likely strategy for the Netherlands in case of a European gas crisis is to scale back on gas export and to rely more heavily on self-provision. Of course, Dutch energy companies are bound by contracts which have been forged in the past. But politicians will likely crank up the pressure to follow the path of least resistance.

Higher prices fuel a winter of discontent in the UK

In the United Kingdom, not a single market has been left untouched by Brexit. While it is clearly a stretch to argue that Brexit is the source of the UK’s energy crisis, it currently adds an extra layer of price volatility in its energy markets.

Take the UK’s electricity market, which has been decoupled from the continent’s internal trading market. Countries that participate in the EU’s internal market use auctions to trade with each other, which continuously balances electricity prices across the continent. With the UK now going its own way, whilst increasingly relying on ‘super-efficient‘ market dynamics, it has become more exposed to significant fluctuations in supply or demand.

These fluctuations make it more challenging to balance the grid, in particular now the makeup of the energy mix changes towards renewables. The UK’s precarious energy situation is entirely reflective of the current resilience-versus-efficiency debate, as we have become keenly aware that disruptions in one part of the world ripple out to affect others.

The gas price surges now threaten the country’s distribution system, which has become increasingly atomized. Many small suppliers seek to make a profit by purchasing energy wholesale and reselling at regulated but higher retail rates. These suppliers typically don’t have the capital to hedge this position.

As the wholesale market is now moving adversely, whilst the Ofgem-regulated rates are sticky and capped (see figure 14) the business model collapses and suppliers fail with it. Customers will be switched to a new supplier, which suddenly has to satisfy demand not budgeted for. That suggests government financial support appears to be required, which eventually needs to be paid back.

The regulator will review the price cap in February, and it will come into effect in April. Unless prices drop rapidly, the potential for a protracted period of higher energy inflation looks likely. This will also have a significant impact on CPI inflation, which might stay around 4% for a few months longer than policy makers had expected. This, in turn, could trigger a rate response from the Bank of England.

One of the key promises of the proponents of Brexit was that it would deliver increased prosperity. In reality, Britain faces shortages, tax hikes, and higher inflation. Even if Brexit isn’t the main cause of most of this, the optics don’t look good at all. Prime Minister Johnson must beware of a new winter of discontent.

Calls for government support may rise with gas

The sharp rise in gas and electricity prices, which is affecting both businesses and households, has already provoked several governments in Europe to intervene. These interventions should dampen the overall impact of rising prices and disruptions, but it is obviously no free lunch.

Indeed, given tight global supply, if demand remains unchanged in Europe due to subsidies obscuring the pricing signal, higher prices will simply be transferred to other economies, many of whom will not be able to afford to match the wealthy EU’s subsidies.

Despite this step being opposed to free-market ideology, we see a number of reasons why EU governments have been quick to step in:

To the extent that higher gas prices are the result of the geopolitical chess game between Germany/Europe and Russia, European governments may be keen to avoid being blackmailed by Moscow; which is an issue that is said to have been raised by Poland –and also the US- at the informal meeting of transport and energy ministers that took place on 22-23 September. That said, ‘humane’ reasons and avoiding a political backlash as a result of the gas crisis is likely to be an all-encompassing driver.

Their interventions may help to avoid significant second order effects. The UK government’s bail-out of US CO2 supplier CF Fertilisers is a case in point. Why would the UK government bail-out a US private company? Because it feared that a halt to CO2 production would cause massive disruption in supply chains, from fizzy drinks to meat.

The past two years have shown the effectiveness and impact of government interventions in the economic process. Whether it is volumes (unemployment) or prices (inflation), everything seems to have become a political choice. Spain’s decision on 14 September to slash energy taxes and impose a temporary windfall tax on the gains of energy companies is a concrete example. The reason here is clearly to limit the impact of rising gas and electricity prices on households. Several other countries have also stepped in already, with Greece providing subsidies to poor families and Italy having supported households already last quarter to make sure electricity bills did not rise more than 10%.

With the covid-19 pandemic not over yet, most governments still enjoy the backing of the central bank, the ECB in this case with its PEPP; as such they can do this without causing significant impact on market/bond yields

In the coming weeks more formal announcements of interventions should be expected. The French government, for example, has already announced it is looking to increase subsidies to poor households, while Italy is looking to rewrite the method to calculate energy bills. Meanwhile, the European Commission has taken up the task to table proposals on how to deal with the surge in energy prices at the EU level. Proposals are expected in the coming weeks, and could well be discussed at the next EU leaders’ summit on 21-22 October. Although the Greek plan to help consumers pay their bills by creating an EU mechanism funded by revenue from extra-ordinary sales of EU carbon emission permits seems unlikely to make the cut, in our view.

The prospect of more government interventions adds an additional layer of complexity to the situation. On the one hand, the economic fall-out from the explosion of gas prices may turn out to be less grave than would otherwise be the case. On the other hand may it prove more difficult to get rid of these policies –if the rise in gas/energy prices turns out be longer lasting/ permanent- and/or could this lead to new distortions elsewhere.

Accelerator or disruptor of the energy transition?

In this piece we show that the rise in gas prices is significant and could have multiple knock-on effects on other markets. If gas prices stay at current elevated levels, we are likely to see a significant increase in inflation compared to our baseline projections. Moreover, we argue that this supply shock is another downside risk to demand further out, as the economy is just recovering from the pandemic shock. Here too, government intervention may well play a key role.

And, geopolitics aside, another key question is whether the current gas crisis could cast a shadow over the much-needed energy transition. In 2021, we again experienced the enormous adverse impact of climate change: soaring temperatures and wild fires in the US, Australia and the South of Europe; floods in Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. Needless to say that action is needed as soon as possible to make a shift towards renewable and clean energy generation.

From this perspective, the rise in high gas prices might even be good news, as it might act as an accelerator to induce households and firms to lower the energy bill via the insulation of homes and offices. Moreover, it may accelerate the shift by households to green alternatives.

That said, installing solar panels, heat pumps or insulating the attic does not come cheap and the question is whether households in particular have sufficient funds to make the required adaptations to their houses in the short term without additional government support. A European gas crisis might encourage politicians to allocate more funds towards these needs, perhaps via the European Recovery Fund. Bear in mind, also, that the rise in electricity prices due to higher gas prices may also lead to a lower pay-out of subsidies to green energy providers by governments, as these subsidies are often based on the gap between the ‘green’ and the ‘grey’ electricity price. In other words, the current crisis need not be a disrupter of the energy transition, and it may even lead to an acceleration.

In the short-term, however, the imminent depletion of global gas inventories on the back of a cold winter might force energy companies to resort to other sources of energy to heat homes, such as coal or even worse, fuel oil. This would definitely throw a spanner in the works towards a cleaner way of energy generation in the near-term.

To highlight this risk, gas made up a larger share of fossil fuel generation than coal in the eastern US in July despite high prices that tend to “prompt gas-to-coal switching for electricity generation […]” the EIA recently said. “This difference is partially because of a longer-term trend of decreasing capacity for coal-fired electricity generation and increasing natural gas-fired capacity”, adding that “Capacity for coal-fired electricity generation has decreased every year since 2011, and gas-fired capacity has increased every year since at least 2009.”

Read More