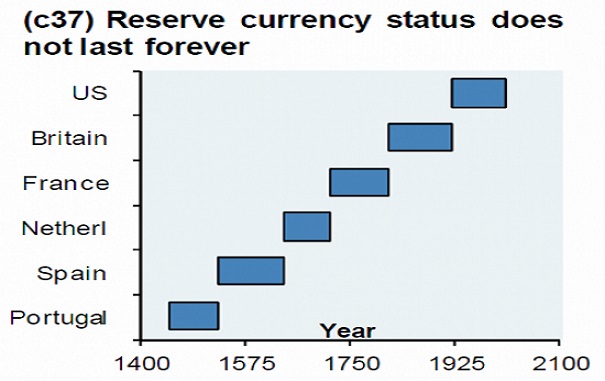

Nothing lasts forever…

And while he falls short of the apocalyptic views of The World Bank’s former chief economist:

“The dominance of the greenback is the root cause of global financial and economic crises,” Justin Yifu Lin told Bruegel, a Brussels-based policy-research think tank.

“The solution to this is to replace the national currency with a global currency.”

…and Zoltan Poszar’s recent warnings of the backlash against US weaponization of the dollar against Russia, noting that

“…wars tend to turn into major junctures for global currencies, and with Russia losing access to its foreign currency reserves, a message has been sent to all countries that they can’t count on these money stashes to actually be theirs in the event of tension… it may make less and less sense for global reserve managers to hold dollars for safety, as they could be taken away right when they’re most needed.”

…and Dylan Grice’s fears over the end of dollar hegemony…

never seen weaponization of money on this scale before…you only get to play the card once. china will make it a priority to need no USD before going for Taiwan. it’s a turning point in monetary history: the end of USD hegemony & the acceleration towards a bipolar monetary order

— Dylan Grice (@dylangrice) February 27, 2022

Goldman Sachs’ Zach Pandl argues that the Dollar’s role as the dominant international currency will likely continue to decline over the coming years, reinforcing his view that the Dollar will weaken over the medium term.

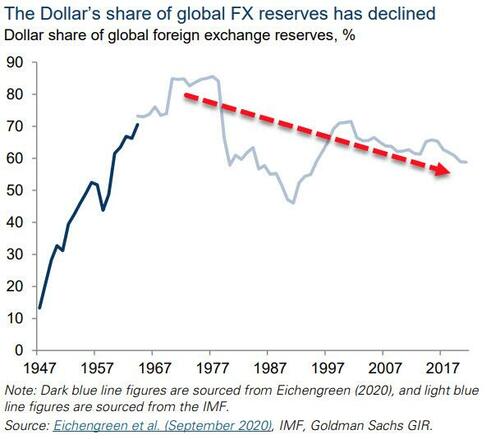

Within a country’s borders, the typical money medium used by households and firms is largely dictated by government rules and regulations. At an international level, by contrast, currency users have a choice. For over six decades, the US Dollar has been the world’s dominant international currency, reflecting both the convenience of using the US currency and a lack of suitable alternatives. But the Dollar’s international role is now under pressure on both fronts. US foreign policy choices may discourage heavy reliance on the Dollar in some cases, while policy changes by other governments, as well as technological innovation, may help facilitate diversification away from it. The Dollar’s share of global foreign exchange reserves peaked at around 85% in the 1970s and fell to below 60% last year, a downward trend we expect to continue over the coming years as other nations pivot toward other fiat currencies and, potentially, alternative money mediums.

US foreign policy doing the Dollar no favors

Pressures on the Dollar’s dominant international role partly stem from US foreign policy choices, in particular, the US’ aggressive use of extraterritorial financial sanctions. Given that all transactions in Dollars eventually pass through the US financial system, preventing US banks and their subsidiaries from transacting with a sanctioned entity effectively shuts that entity out of the global financial system. For example, an EU business could be prevented from trading with Iran, even if it’s legal under domestic EU law, because its bank could run afoul of US sanctions. For this reason, the EU Commission has said that US sanctions and trade disputes with other countries represent a threat to the EU’s economic and monetary sovereignty. Overuse of sanctions by the US could discourage other countries from transacting in the Dollar in the first place, a risk that US officials are well aware of. Former Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew said in 2016 that the US “must be conscious of the risk that overuse of sanctions could undermine our leadership position within the global economy, and the effectiveness of our sanctions themselves… if they excessively interfere with the flow of funds worldwide, financial transactions may begin to move outside of the United States entirely—which could threaten the central role of the US financial system globally.” Similarly, former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger said in 2014: “I do have a number of problems with the sanctions [on Russia for its annexation of Crimea]. When we talk about a global economy and then use sanctions within the global economy, then the temptation will be that big countries thinking of their future will try to protect themselves against potential dangers, and as they do, they will create a mercantilist global economy.”

Will the recent imposition of sanctions on Russia’s central bank over the war in Ukraine be the straw that breaks the camel’s back? Countries hold foreign exchange reserves as a store of value to use in times of crisis. But when the Russian government recently needed its reserves to stabilize the country’s financial system, they were immobilized by Western sanctions. As a result, other nations may worry that the value of their Dollar-denominated financial assets is only as solid as their relationship with the US at the time, which may motivate sovereign investors to search for alternative assets, including a more diversified mix of foreign currency holdings.

Dollar facing stiffer competition

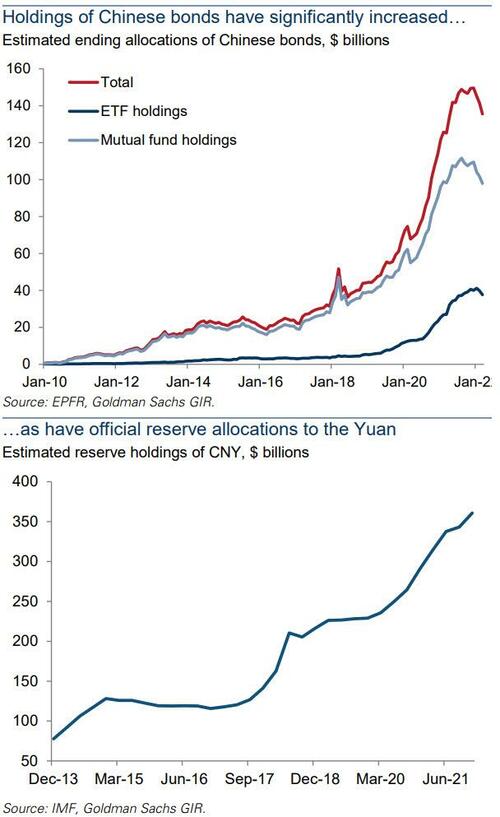

Competition for the Dollar has also gotten stiffer, especially from China, which has taken significant steps to modernize and open up its financial system, leading to a wave of fixed income portfolio inflows in recent years. Since 2016, mutual fund and ETF holdings of Chinese bonds have increased sixfold and official reserve allocations to the Yuan have increased almost fourfold.

We expect both of these trends to continue over the coming years, due to likely increases in China’s weight in major benchmark indices, as well as the Yuan’s relatively high nominal and real yields, its relatively cheap valuation, and China’s increasing strategic importance. The Bank of Israel, for instance, cited related considerations when explaining the ramp-up of its Yuan-denominated reserve assets this year. And China’s efforts to develop the first major central bank digital currency (CBDC) may also help facilitate international use of the Yuan, perhaps first by Chinese tourists abroad and partner countries in the Belt and Road Initiative.

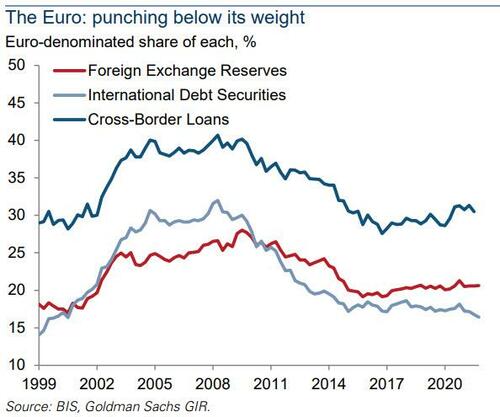

Separately, recent institutional upgrades to the EU—as well as the prospect of positive cash yields—could help the Euro compete with the Dollar in international currency choice over time. While the Euro functions as an international currency today, primarily in trade with its regional neighbors, it has fallen well short of the project’s initial aspirations, and is generally thought to be “punching below its weight”, for several reasons.

-

First, the Euro area has lower macroeconomic stability than other highly-developed economies, due in large part to an incomplete fiscal union and therefore more persistent internal imbalances.

-

Second, the Euro area lacks a large supply of the type of high-quality government bonds sought by sovereign investors.

-

And third, Europe lacks the geopolitical reach of the US, in part because foreign affairs and defense policy are still conducted at the member state level. While the European Union has a coordinator for regional foreign policy, and arguably some aspects of “soft power”, it lacks the type of global military arrangements that help underpin Dollar dominance.

However, Europe tends to take steps forward in times of crisis, and the policy responses to recent disruptions are likely building a better foundation for the single currency for the future. While not billed as an effort to speed up Euro internationalization, the EU Recovery Fund/NGEU project— Europe’s response to the Covid pandemic—helps address the Euro’s structural weaknesses, and may therefore have positive implications for the currency’s global use over time. The program addresses macroeconomic instability through intraregional transfers—in effect, a step toward fiscal federalism— and also creates a new supply of highly-rated government bonds, which should be attractive to sovereigns and other international investors. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine presents new challenges for the EU and Euro area, and may damage economic growth over the short term, but could be positive for the Euro over the long term if it results in an increase in defense spending and more “hard power” for the region.

Lastly, while cryptocurrencies are still in their infancy today, the technology could eventually be applied to certain types of international payments, possibly displacing the Dollar. The Western conflict with Russia, for example, demonstrates the key challenge that cryptocurrency networks like Bitcoin aim to solve: the need for parties who may not know or trust each other to transact value. Gold often served this role as an alternative international money medium to fiat currency in the past. Before Bitcoin, there was no digital equivalent to gold, because digital payments required a centralized intermediary. While there is no guarantee that Bitcoin will serve this purpose in the future, its foundational blockchain technology demonstrates that a scarce digital medium can be created through cryptographic algorithms and the careful use of economic incentives, and some market participants may prefer this type of digital medium to traditional fiat currencies for certain types of international payments.

Declining dominance, eventually a declining Dollar

In recent days and weeks, the Dollar has continued to appreciate as markets have discounted even more monetary tightening by the Fed, and, over the near term, the outlook for rate hikes in the US relative to other economies will likely remain the primary driver of Dollar exchange rates. But over a medium-term horizon, the balance of risk around the Dollar is skewed significantly to the downside, in our view, due to the currency’s high valuation (more than 10% overvalued on our standard models) and three potential structural changes in global capital flows:

(i) fixed income flows back to the Euro area as the ECB exits negative rates,

(ii) outflows from US equities on any sustained underperformance, and

(iii) de-Dollarization efforts by official institutions designed to reduce exposure to Dollar-centric payment networks.

The Dollar maintains its role as the world’s leading international currency for many reasons – with reinforcing complementarities or “network effects” a key factor – so this structure will not change overnight. But the shifting tactical and structural trends reinforce our conviction in a weaker Dollar over the medium term.