Foreword: This contribution does not intend to provide a profound analysis or exhaustive essay on the complex and rich history of Song Dynasty painting. It intends to offer a modest, cursory glimpse into classical Chinese thought… which can offer us valuable lessons for our views of the world and the cosmos as the Western world continues to collapse.

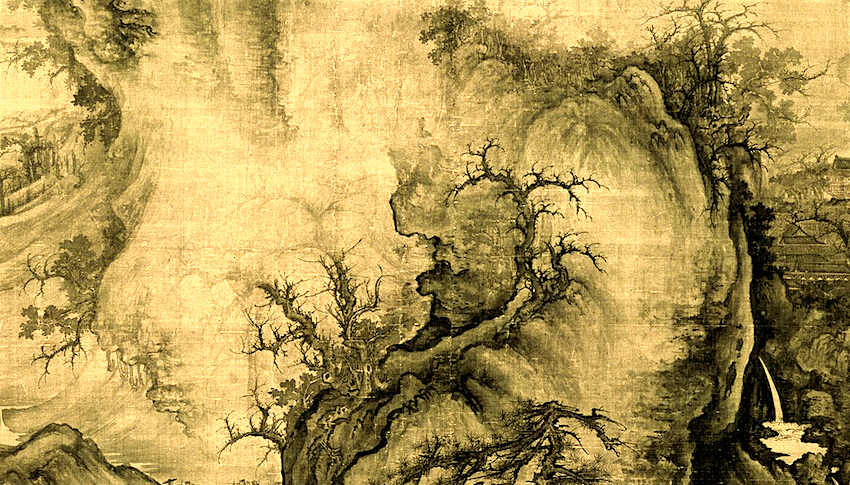

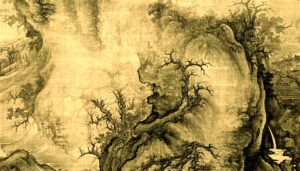

Guo Xi (c. 1020 – c. 1090) was a landscape painter and from Wenxian in the Henan Province who lived during the Northern Song dynasty. Early in his career as an artist, he painted a vast number of screens, scrolls and murals on the walls of major palaces and halls. Producing monumental landscape paintings that featured mountains, pine trees and scenery enveloped in mist and clouds, he served as a court painter under Emperor Shenzong (who reigned 1068–1085) and was tasked with painting the walls the newly built palace in the capital. Guo was promoted to the highest position of Painter-in-Attendance in the court Hanlin Academy of Painting.

Asked why he decided to paint landscapes, Guo Xi answered: “A virtuous man takes delight in landscapes so that in a rustic retreat he may nourish his nature, amid the carefree play of streams and rocks, he may take delight, that he might constantly meet in the country fishermen, woodcutters, and hermits, and see the soaring of cranes and hear the crying of monkeys. The din of the dusty world and the confinement of human habitations are what human nature habitually abhors; on the contrary, haze, mist, and the haunting spirits of the mountains are what the human nature seeks, and yet can rarely find.”

The Song Dynasty

The Song dynasty (960–1279 AD), founded by Emperor Taizu of Song (following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou Dynasty, ending the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period), was a culturally rich and sophisticated age for China. It saw great advancements in the visual arts, music, literature, philosophy, science, mathematics, technology and engineering. Officials of the ruling bureaucracy, who underwent a strict and extensive examination process, reached new heights of education in Chinese society, while Chinese culture was enhanced and promoted by widespread printing, growing literacy, and various arts.

The expansion of the population, growth of cities, and emergence of a national economy led to the gradual withdrawal of the central government from direct involvement in economic affairs. The lower gentry assumed a larger role in local administration and affairs. Social life during the Song was vibrant. Citizens gathered to view and trade precious artworks, the populace intermingled at public festivals and private clubs, and cities had lively entertainment quarters. The spread of literature and knowledge was enhanced by the rapid expansion of woodblock printing and the 11th-century invention of movable-type printing. Philosophers such as Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi reinvigorated Confucianism with new interpretations, infused with Buddhist ideals, and instituted a new organization of classic texts that established the doctrine of Neo-Confucianism.

The dynasty was divided into two periods: Northern Song and Southern Song. There was a significant difference in painting trends between the Northern Song period (960–1127) and Southern Song period (1127–1279). The paintings of Northern Song officials were influenced by their political ideals of bringing order to the world and tackling the largest issues affecting the whole of their society, hence their paintings often depicted huge, sweeping landscapes. On the other hand, Southern Song officials were more interested in reforming society from the bottom up and on a much smaller scale, a method they believed had a better chance for eventual success.

The Song court maintained diplomatic relations with Chola India, the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt, Srivijaya, the Kara-Khanid Khanate in Central Asia, the Goryeo kingdom in Korea, and other countries that were also trade partners with Japan. Chinese records even mention an embassy from the ruler of “Fu lin” (i.e. the Byzantine Empire), Michael VII Doukas, and its arrival in 1081.

During the Song dynasty art reached a new level of sophistication with the further development of landscape painting, works of which are today considered some of the greatest artistic monuments in the history of Chinese visual culture. The painting of landscapes or shan shui, (the literal translation of the Chinese term for landscape – “shan” meaning mountain, and “shui” meaning river) in the Song period was grounded in Chinese philosophy.

“Zao Chun Tu” (“Early Spring”) of Guo Xi

Guo Xi’s Early Spring, considered one of the greatest works in the history of Chinese art, is an enormous hanging scroll that portrays a large mountain and its nature within in a constant state of metamorphosis.

The painting seems alive with movement as Yin turns into Yang and vice versa. The painter achieved this feeling of rhythmic motion by alternating areas of dark ink and unpainted surface, massive rock and airy valleys, and dense foliage and light mist.

One of Guo Xi’s techniques was to layer ink washes and texture strokes to build up credible, three-dimensional forms. Strokes particular to his style include those on “cloud-resembling” rocks, and the “devil’s face texture stroke,” which is seen in the somewhat pock-marked surface of the larger rock forms.

“The angle of totality”

With his innovative techniques for producing multiple perspectives, Guo was aiming for something he called “the angle of totality.” Because a painting is not a window, there is no need to imitate the mechanics of human vision and view a scene from only one spot! Guo is particularly concerned with the effect that distance has on viewing a landscape, and how detachment and nearness can change the appearance of a single object multiple times. This type of visual representation is also called “Floating Perspective”, a technique that displaces the static eye of the viewer and highlights the differences between Chinese and Western modes of spatial representation.

Unlike the aspiration central to Western landscape painting – to paint a particular location from a fixed standpoint, Chinese landscape painting aimed to incorporate the essence of thousands of mountains, the accumulated sights of a lifetime into one composite landscape. Thus, to look upon a landscape painting in the Chinese tradition was to feel connected to the full scope of places and living things.

The relationship between humankind and the mountain being sought in Guo Xi’s painting is one of compatibility, participation, and interconnectedness. According to Guo Xi’s own words, cited by his son in his treatise “The Lofty Message of Forests and Streams”, “The mountain lives only in the act of wandering. The mountain’s form changes with every step. A mountain seen up close has one aspect, and it has another a few miles away, and yet another one from further away. Its shape changes with each step. The front view of a mountain has one view, another view from the side and another from behind. Its appearance changes from every angle, as many times as it does the point of view. So, it is necessary to realize that a mountain combines in itself several thousand shapes.” These comments suggest that the mountain is only conceivable from multiple standpoints, as if one were wandering through it. If we look carefully at the bottom, middle, and top sections of Guo Xi’s painting in this way, we will see an illustration of shifting perspectives, a typical feature in Chinese landscape painting. The bottom three boulders with accompanying trees seem to be viewed as if we are standing above them; the middle register looks as if we are viewing it straight on; and the top portion, the regal summit, seems to be viewed from below. We are constantly adjusting our eyes to take in a fresh point of view. Guo Xi called this exercise “viewing the form of a mountain from each of its faces”. The viewer thus becomes a traveller in the painting, which offers him the experience of moving through space and time.

Like many other rare early works from the imperial art collection, Early Spring resides today in the National Palace Museum in Taiwan. It was among the masterpieces appropriated there in 1949 when Chiang Kai-Shek’s army fled mainland China after the victory of the Communists in the Civil War.

Linquan Gaozhi – “The Lofty Message of Forest and Streams”

A text entitled “Linquan Gaozhi” (“The Lofty Message of Forest and Streams”) is a collection of remarks and statements of Guo Xi that was compiled by his son, Guo Si with his own annotations and which became one of the greatest treatises on the theory of landscape painting in China.

In an excerpt from the “Treatise on Mountains and Waters” Guo Xi remarks: “The clouds and the vapours of real landscapes are not the same in the four seasons. In spring they are light and diffused, in summer rich and dense, in autumn scattered and thin, and in winter dark and solitary. When such effects can be seen in pictures, the clouds and vapours have an air of life. The mist around the mountains is not the same in the four seasons. The mountains in spring are light and seductive as if smiling; the mountains in summer have a blue-green colour, which seems to be spread over them; the mountains in autumn are bright and tidy as if freshly painted; the mountains in winter are melancholic and tranquil as if sleeping.

In this treatise Guo Xi’s son describes how his father received special recognition from the emperor for these magnificent works, and how the artist would spend days in silent contemplation before undertaking a mural, at which point, having prepared himself mentally, he would produce entire paintings in a single burst of creation. Indeed Guo Xi would likely have been harried by his workload day in and day out, without the leisure for such introspection. However, Guo Si describes his father’s works over and over as being imbued with spirit, insisting that they are not mere journeyman pieces but rather the “works” of an artist of the highest cultural refinement.

According to Maromitsu Tsukamoto, Associate Professor at Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, one particular passage by Guo Si captures his father’s true thoughts: “…«My father, Guo Xi, told me: “The Tang poet Du Fu, seeing a landscape painting by the famous shan shui painter Wang Zai, declaimed ‘Ten days to paint one stream! Five days to paint one rock!’ And my response: ‘Yet it is exactly thus!’”…» Guo Xi’s protest that one must not be hasty, that one cannot produce good work without putting in the proper time, was surely his frank and honest intention, overwhelmingly busy as he was painting enormous murals for the imperial court. The complex affection in these words uttered between parent and child a thousand years ago, together with those works, evoke a deep sympathy even in those of us living in today’s contemporary world.”

The Philosophical Aspects: Chinese landscape painting unites Confucian philosophical concepts with Taoist and Buddhist thinking about nature.

According to the French philosopher and sinologist François Jullien, the dual Chinese term for landscape shanshui (“shan = mountain”/ “shui = water”) is reflective of the interaction between complementary dualities (yin and yang). Jullien writes: “We have what tends toward heights (the mountain) and what tends toward depths (the water). The vertical and the horizontal, High and Low, at once oppose and respond to each other. We have, too, what is immobile and impassive (the mountain) and what is in constant motion, forever undulant and flowing (the water). Permanence and variance are at the same time confronted and associated. We have, moreover, what possesses form and presents a relief (the mountain) and what is by nature formless and takes the form of other things (the water). The opaque and the transparent, the solid and the dispersive, and the stable and the fluid blend together and heighten each other.

“Instead of the unitary term “landscape”, China speaks of an endless play of interactions between contrary factors that pair up, forming a matrix through which the world is conceived and organized. Here there is no governing, dominating Subject (the Renaissance subject of Europe), no individual to hold the world from his vantage point and to develop his initiative freely within it, as if he were God. There is no ‘object’ held in vis-à-vis, nothing to be ‘cast’ ‘before’ the individual’s eye, nothing to spread out passively for his inspection and cut itself out differently with his every step. Against this monopolizing power of sight, China offers the essential polarity through which world-stuff enters into tension and deploys. No human-stuff detaches from this. The human remains implicit, contained within these multiple implications, because the vis-à-vis thus established lies within the world; it is between the ‘mountains’ and the ‘waters’.”

How does a Song dynasty Chinese landscape painting envision humanity’s relationship with the cosmos? The Tao sees the human being in the vastness of the cosmos as a minor presence. The tiny scale of humans relative to the mountains in a typical Chinese landscape painting suggests that we humans coexist with many other living things. Humans are integrated into a larger whole rather than celebrated as a towering presence. The Neo-Confucian philosophy, developed during the Song dynasty, cultivated a profound respect for all living things and emphasized humanity’s interconnectedness with a wider universe.

Chinese classical landscape painting, as a whole, unites Confucian philosophical concepts with Taoist and Buddhist thinking about nature. For example, the life force in both Taoism and Buddhism is represented by water. According to the Tao Te Ching, “the highest good is like water, because water excels in benefiting the myriad creatures without contending with them and settles where none would like to be, it comes close to the Way.” Waterfalls or river streams in Chinese landscape paintings evoke a sense of possibility and opportunity because water’s fluidity pierces through rocks and opens space for manoeuvring. Buddhists also revere the thunderous downpour of a waterfall and the attendant vapour spiralling upward. In Buddhism, the flow of mist and water suggests the circulation of wisdom through the body, mind, and universe achieved through meditation. In Tibetan thanka paintings, for example, the clouds pictured above waterfalls represent the enlightened essence shared by all living beings.

François Jullien argues that the Chinese placed central importance on the activity of breathing as the defining characteristic of life. Whereas the Greeks “privileged the gaze and the activity of perception”, the Chinese conceived of reality in terms of qi, or breath-energy. The activity of breathing out and in unites humans to the alternating rhythms of heaven and earth. In the Taoist classic Tao Te Ching, the universe is pictured as a great bellows engaged in a cosmic process of respiration.

Emptiness

Because Chinese painters put “spirit” (qi) in the most important position for painting, they gradually let the spirit of nature, the human spirit and the spirit of brush and ink be displayed in the picture. This is to make the initially apparent “empty space” in the painting become the main feature for expressing aesthetic spirit. The ancient Chinese painters often said that they did not seek similitude to that which their eyes perceived, but pursued the spirit of the reality before and around them.

Whether from a historical perspective or a logical perspective, the aesthetics of Lao Tse, principal author of the Tao Te Ching and founder of philosophical Taoism, should be taken as the starting point of the history of Chinese aesthetics. Even though there are substantial differences between Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, they all have a wide and long influence on traditional Chinese culture and values. The aesthetic thoughts of each express a unified artistic conception that combines tangible and intangible, solidness and emptiness, and limited and unlimited, thus giving birth to this unique form of artistic expression of the intended blank.

20th century Chinese aesthetician Zong Baihua believes that Chinese painting attaches the most importance to “blank space”. “The blank space is not really blank, but the place where the spirit moves. If you take the emptiness as whiteness then it becomes complete nothingness; if you take the solid part as concrete completely, then the object will lose its liveliness; only by putting emptiness into solidness and turning solidness into emptiness, there is space for endless imagination.” The void is undefined, undifferentiated and, therefore, with infinite possibilities for transformation.

The space in Chinese painting is constructed with association and imagination, and the method of combining being and non-being is an essential technique to create a vast and far-reaching space. Just like the core content presented by the precepts of ancient Chinese Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, reality and nihility, being and non-being are closely linked, and they are a unity that is both conflicting and indivisible. Without the exchange between existence and nonexistence, there would be no rhythm and spirit in art.

And indeed, Lao-Tse never ceased to advocate the inexhaustible resource of emptiness: “The thirty spokes converge in a hub: where there is nothing, there is the use-functioning of the chariot. Without the void in the hub, the wheel would not turn; without the void in the clay, the vase would not contain water…” The void proceeds from the hollowing out of the full, and the full is, in turn, hollowed out by the void. Neither opposed nor separated from each other, these two states, the empty and the full, “are structurally correlated and exist only through each other”. All that remains for the Taoist painter or poet, instead of freezing and reifying, is to accomplish through his or her gesture this breathing that will fill the void and desaturate the full.

The distinguished scholar specialised in Buddhism and East-West comparative philosophy Professor Kenneth K. Inada stated: “For the Buddhist, it is the ‘discovery’ of emptiness (sunyata) in the becomingness of things or emptiness in the beings-in-becoming. For the Taoist, it is the ‘discovery’ of nothing (wu) in the Tao of things.”

The Tao has no name, nor can it be determined. Still, it is a cosmic force, the mystic process of the world, the inner nature of everything that exists, nature, which is not discovered, but revealed. It is the ruling force of the eternal change that inspires all, acts by non-acting (wu-wei), creates, not by making, but rather by growing, it creates from within. Taoism is an affirmation of the unconventional knowing by developing of the so-called peripheral or non-self-aware seeing, unintelligible penetration into everything, into the nature of things. Both Taoism and Buddhism are philosophies of the experience. Both are holistic schools. Things are not opposite, they are One. Yin and Yang are only the energetic models of its occurrence. There is no dichotomy.

The Chinese philosophical point of view, which implies a perception of the things in their wholeness and eternal movement, as integral parts of a functional whole of the existence, and not as separate fragments. Chinese painting can thus be understood as a visible realization of what is in the process of being thought. “The Eastern view of things prevented any dichotomous treatment of anything from the outset and in turn fostered exploration into the fullness of the becoming process.” (Inada, 1997)

“Is not the space between Heaven and Earth like a great bellows?” asks Lao Tse. “Empty, it is not flattened, and the more you move it, the more it exhales; but the more you talk about it, the less you grasp it…” It is not surprising, therefore, that the Chinese conceived of the original reality, not according to the category of being and through the relation of form and matter (the Chinese did not conceive of “matter”), but as “breath-energy”, as qi (“becoming”).

Jullien writes: “All landscape apprehended in this play of correlations is the entirety of the world in its vibrancy: not a world that beckons from Elsewhere but a world perceived in the to-and-fro of its respiration. This same tension of living is what Chinese painting captures in landscape.”

Some references:

“La grande image n’a pas de forme ou du non-objet par la peinture” – François Jullien Seuil 2003

Inada, Kenneth K. “A theory of oriental aesthetics: a prolegomenon”, Philosophy East & West, Aug. 1997, Vol.47, Issue 2

François CHENG, Á l’orient de tout (Gallimard Poesie Gallimard N° 403 8 Septembre 2005)

When the artist begins to speak – The Linquan Gaozhi: a tale of a painter and his son 1000 years ago by Maromitsu Tsukamoto, Associate Professor, Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, Tokyo

https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/focus/en/features/z1304_00060.html

Northern Song Landscape Painting

https://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/painting/4ptgnsla.htm

Aesthetics and Philosophical Interpretation of the ‘Intended Blank’ in Chinese Paintings – Tianyi Zhang

https://ijahss.net/assets/files/1633890843.pdf

China Online Museum

https://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/guo-xi/

An Environmental Ethic in Chinese Landscape Painting