Here’s How Afghanistan’s Economy Changed During 20 Years Of War

Amateur and professional bean counters are starting to take stock of what, exactly has changed during 20 years of war between the US and the Taliban. And while as China and Russia prepare to strengthen economic ties with the Taliban, the FT has published a mildly comprehensive rundown of how Afghanistan’s economic situation has changed since the US invasion began in 2001.

Speaking to the FT for a story about Afghanistan’s economic development, Gareth Price, senior research fellow at think-tank Chatham House, said that while Afghanistan had “changed dramatically” in social terms, “none of the main domestic generators of growth — notably mineral reserves — have been significantly tapped, aside from illegal mining”.

In other words, the Taliban has plenty of natural resources to plunder, and an eager buyer with China already making entrees to the Taliban (despite their obvious ideological conflict, just another example of China’s unyielding commitment to “true” socialism).

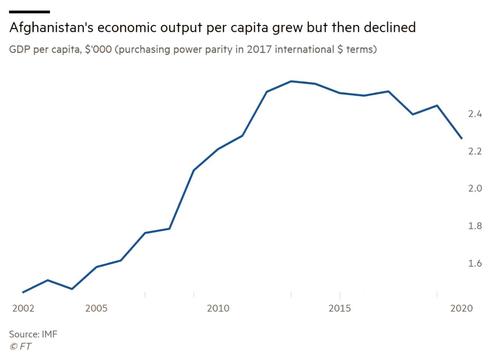

Living standards saw solid improvement during the early years of the US occupation, but the pace of improvement leveled off around 2010, when corruption in graft within the new Afghan government started getting really out of control.

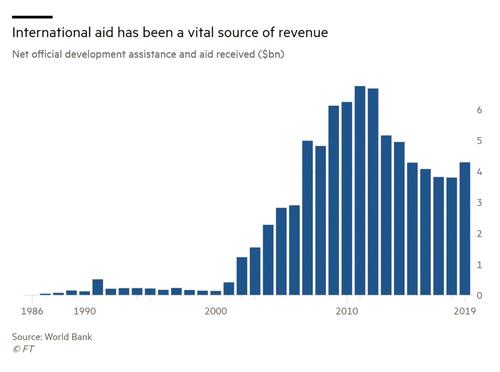

One of the biggest contributing factors: Aid flows fell from about 100% of GDP in 2009 to 42.9% in 2020 according to the World Bank, sending living standards lower as the services sector’s growth was constrained.

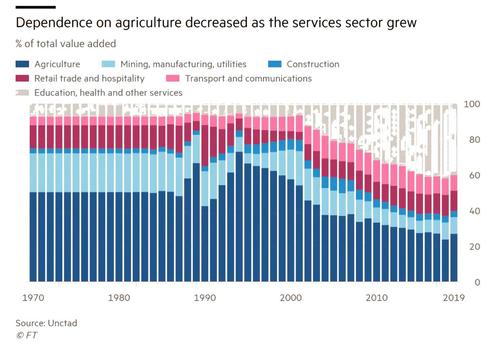

While services growth has remained somewhat stagnant, the country’s economy has continued to depend largely on agriculture. As of 2021, roughly half of its official exports are composed of grapes and other fresh fruit, although it’s importance has declined somewhat.

However, as one analyst pointed out, most of these figures should be taken with a grain of salt, since the illegal opium trade comprises a major portion of Afghanistan’s economy, along with other black-market trades from energy, to methamphetamine and other drugs.

While the Taliban are only just assuming control of much of Afghanistan’s legitimate economy, an editorial published last week in the NYT by a pair of Afghanistan experts alleged that the group has long controlled much of the country’s illegitimate, smuggling-based economy.

With this in mind, the Taliban’s advance has forced neighbors to confront a dilemma: They could either continue to trade, giving the Taliban more power and legitimacy, or deny themselves trade revenues and accept the financial pain. As pressure from China, Pakistan and Russia mounts, more countries will have little choice but to accept the status quo, with the Taliban returned to power in Kabul.