By Michael Every and Matteo Iagatti of Rabobank

It is impossible to ignore the current shipping crisis and its impact on global supply chains

A common view is that this is all the result of Covid-19. Yet while Covid has played a key role, it is only part of a far larger interconnected set of problems

This report examines current shipping market dynamics; overlooked “Too Big to Sail” structural issues; a brewing political tsunami as a backlash; possible Cold War icebergs ahead; and the ‘ship of things to come’ if maritime past is a guide to maritime future

The central argument is that while central banks and governments both insist inflation is transitory and will fall once supply-chain bottlenecks are resolved, shipping dynamics suggest they are closer to becoming systemically entrenched

Moreover, both historical and current trends towards addressing such problems suggest potential global market disruptions at least equal to the shocks we have already experienced. Many ports will get caught in this storm, if so

Ready to ship off?

It is impossible to ignore the current shipping crisis and its impact on global supply chains and economies.

Businesses face huge headaches as supply dries up. Consumers see bare shelves and rising prices. Governments have no concrete solutions – save the army? Economists have to discuss the physical economy rather than a model. Central banks still assume this will all resolve itself. And shippers make massive profits.

The giant Ever Given, which blocked the Suez Canal for six days in March 2021, is emblematic of these problems, but they run far deeper. This report will explore the shipping issue coast-to-coast, and past-to-present in six ‘containers’:

“Are you shipping me?”, a deep-dive into market dynamics and supply-demand causes of soaring shipping prices;

“To Big to Sail”, a key structural issue driving things;

“Tsunami of politics” of the looming backlash to what is happening;

“Cold War icebergs” of fat geopolitical tail risks;

“Ship of things to come?”, asking if the maritime past is a potential guide to maritime future; and

“Wait and sea?”, a strategic overview and conclusion.

Are You Shipping Me?

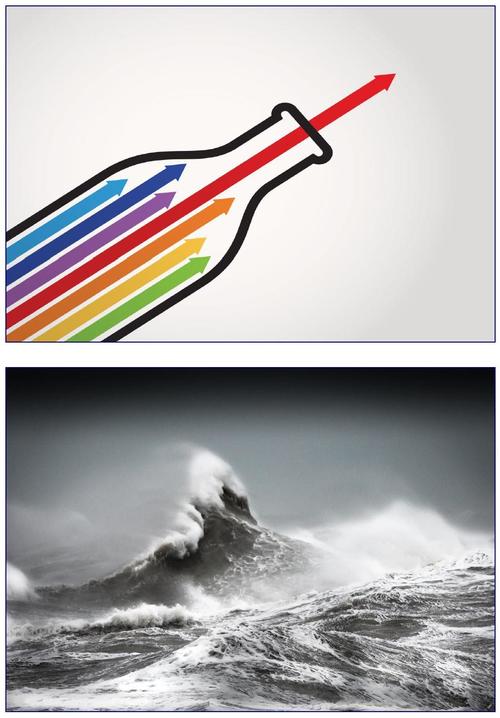

Since 2020, global shipping has been frenetic, with equally frenetic shipping rates (figure 2); difficulties for both businesses and consumers; and container-carrier profits.

Is Covid-19 driving these developments, or are there other structural and cyclical factors at play? Let’s take stock.

One root of the problem…

In 2020, COVID-19 become a global pandemic, and lockdowns ensued: factories, restaurants, and shops all closed, bringing global supply chain almost to a halt. In this context, container carriers had no visibility on future demand and did the only reasonable thing: cut capacity.

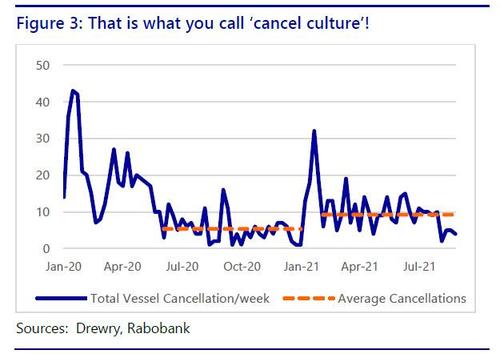

There is no economic sense in moving half-empty ships across the globe; it is costly, especially for a sector operated on tiny margins for a very long time. The consequence was widespread vessel cancellations, which soared in the first months of 2020 (figure 3). Progressively, more trade lines and ports were involved as containment measures were enacted globally.

By H2-2020, virus containment measures were over in China, and many other nations eased them too. Shipping cancellations did not stop, however, just continuing at a slower pace. Indeed, capacity cuts have plagued supply-chains in 2021.

Excluding the January-February peaks, from March to September 2021, an average of 9.2 vessels per week were cancelled, four vessels per week more than the previous off-peak period of July to December 2020 (figure 3).

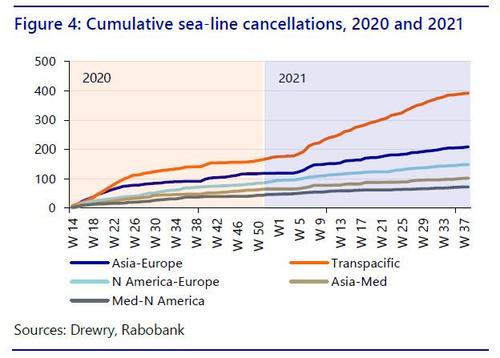

Cumulative cancellations (figure 4) underline the problems. Transpacific (e.g., China-US) and Asia-Northern Europe lines saw the largest capacity cuts, but Transatlantic and Mediterranean-North America vessels also reached historic levels of cancellations.

Transpacific and Asia-Europe lines are the backbone of global trade, each representing 40% of the total container trade. More than 3 million TEUs (Twenty-foot Equivalent Units, a standard cargo measure) are moved on Transpacific and Asia-Europe lines in total per month. Due to cancellations, more than 10% of that capacity was lost in early 2020.

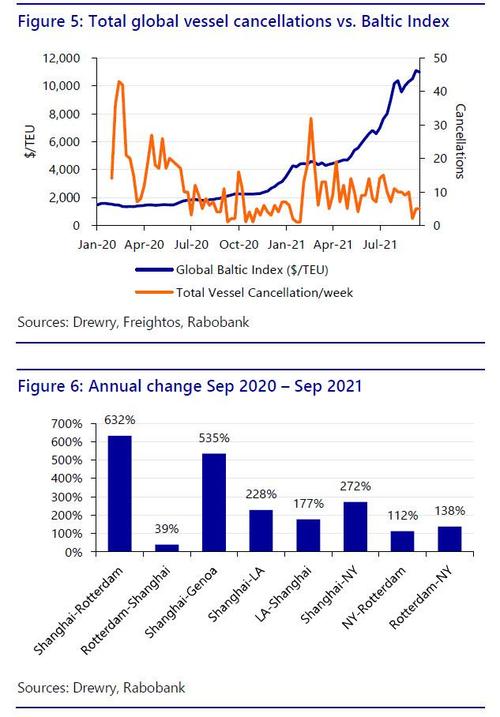

In such a context, it was only normal to expect a rise in container rates. Over January-December 2020 the Global Baltic index (the world reference for box prices) increased by 115% from $1,460 to $3,140/TEU.

However, as figure 2 shows, things then changed dramatically in 2021 for a variety of reasons.

As can be seen (figure 5), cancellations alone cannot explain the price surge seen in the Baltic Dry Index — the leading international Freight Rate Index, providing market rates for 12 global trade lines– and on key global shipping routes (figure 6).

So what did?

We have instead identified five key themes that have pushed up shipping costs, which we will explore in turn:

Suez – and what happened there;

Sickness – or Covid-19 (again);

Structure – of the shipping market;

Stimulus – most so in the US; and

“Stuck” – as in logistical congestion.

Suez

On March 23rd 2021, a 20,000TEU giant vessel, the Ever Given, owned by the Taiwanese carrier Evergreen, was forced by strong winds to park sideways in the Suez Canal, ultimately obstructing it. For the following six days, one of the fundamental arteries of trade between Europe, the Gulf, East Africa, the Indian Ocean, and South East Asia was closed for business.

While the world realized how fragile globalized supply chains are, carriers and shippers were counting the costs.

370 ships could not pass the Canal, with cargoes worth around $9.5bn. Every conceivable good was on those ships. The result was more unforeseen delays, more congestions and, of course, more upward pressure on container rates.

Sickness

New COVID-19 Delta variant outbreaks in 20201 forced the closure of major Chinese ports such as Ningbo and Yantian causing delays and congestion that reverberated both in the region and globally. Vietnamese ports also suffered similar incidents.

These closures, while not decisive blows, contributed to taking shipping capacity off the global grid, hindering the recovery trend. They were also signals of how thin the ice is that global supply chain are walking on. Indeed, Chinese and South-east Asian ports are still suffering the consequences of those earlier closures, with record queues of ships waiting to unload.

Structure

When external shocks cause price spikes it is always wise to look at structure of the sector in which disruption caused the price spike. This exercise provides precious hints on what the “descent” from the spike might look like.

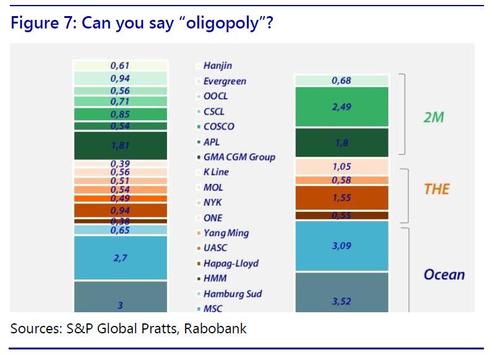

Crucially, in the shipping sector, consolidation and concentration has achieved levels that few other sectors of the economy reach.

In the last five years, carriers controlling 80% of global capacity became more concentrated, with fewer operators of even larger size (figure 7). However, this is just the most obvious piece of the puzzle.

In our opinion, the real change started in 2017, when the three main container alliances (2M, THE, and Ocean) were born. This changed horizontal cooperation between market leaders in shipping. The three do not fix prices, but via their networks capacity is shared and planned jointly, fully exploiting economies of scale that are decisive to making a capital-intensive business profitable and efficient. Unit margins can stay low as long as you move huge volume with high precision, and at the lowest cost possible.

To be able to move the huge volumes required by a globalized and increasingly e-commerce economy at the levels of efficiency and speed demanded by operators up and down supply chains, there was little other options than to cooperate and keep goods flowing for the lowest cost possible at the highest speed possible. A tight discipline of cost was imposed on carriers, who also had to get bigger.

This strategy more than paid off in the Covid crisis, when shippers demonstrated clear minds, efficiency in implementing capacity control, and a key understanding of the elements they could use to their advantage: in other words – how capitalism actually works.

Carriers did not decide on the lockdowns or port closures; but they exploited their position in the global market when the pandemic erupted. In a recent report, Peter Sands from BIMCO (the Baltic and International Maritime Council) put it as follows: “Years of low freight rates resulting in rigorous cost-cutting by carriers have left them in a great position to maximise profits now that the market has turned.”

Crucially, this market structure is here to stay – for now. It is a component of the global system. Carriers will continue to exert pressure and find ways to make profit but, most importantly, they will make more than sure that, this time, it is not only them that end up paying the costs of rebalancing within the global system.

In short, the current market allows carriers to make historic levels of profits. However, in our view this is not the end of the story – as shall be shown later.

Stimulus

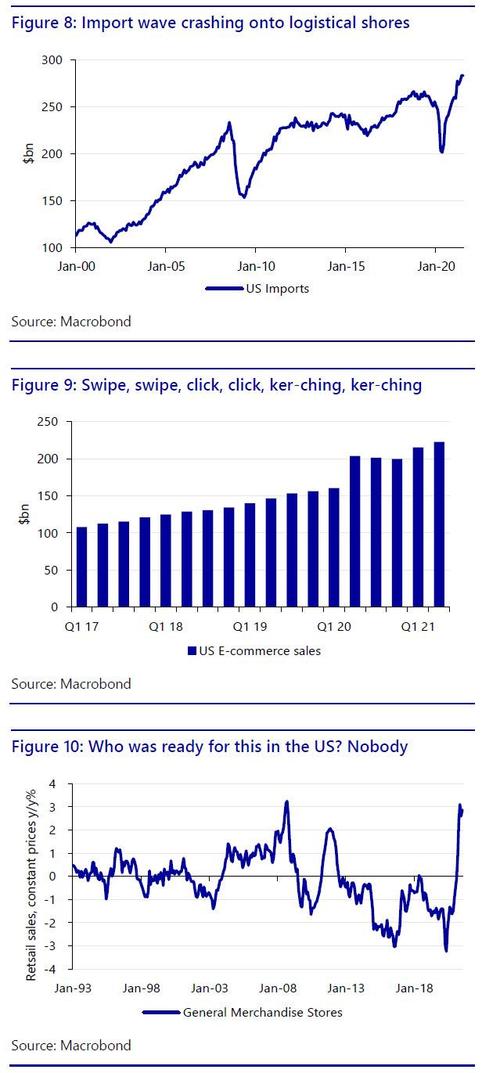

2020 and 2021 saw unprecedented economic shocks from Covid-19, as well as unprecedented economic stimulus from some governments. In particular, the US government sent out direct stimulus cheques to taxpayers. With few services to spend the money on, it was instead centred on goods. Hence, consumer demand for some items is red-hot (figures 8-10).

The consequences of this surge in buying on top of a workforce still partly in rolling lockdowns, and against a backlog of infrastructure decades in the making, was obvious: logistical gridlock.

Moreover, with the US importing high volumes, and not exporting to match, and its own internal logistics log-jammed, there has been a build-up of shipping containers inside the US, and a shortage elsewhere. Shippers are, in some cases, even dropping their cargo and returning to Asia empty: the same has been reported in Australia.

Against this backdrop, the US is perhaps close to introducing further major fiscal stimulus, with little of this able to address near-term infrastructure/logistical shortfalls. Needless to say, the impact on shipping, if such stimulus is passed, could be enormous.

As such, while central banks and governments still insist that inflation is transitory, supply-chain dynamics suggest it is in fact closer to becoming systemically entrenched.

Stuck

In normal times, a surge in consumer spending would be a bonanza for everyone: raw material producers, manufacturers, carriers, shippers, and retailers alike. In Covid times, this is all a death-blow to global supply chains.

Due to misplaced global capacity, high export volumes cannot be moved fast enough, intermediate goods cannot reach processors in time, and everybody is fighting to get a container spot on the ships available.

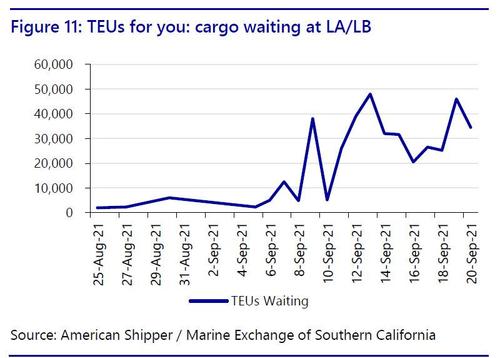

Ports cannot handle the throughput given the backlog of containers that are still waiting to be shipped inland or loaded on a delayed boat. It is not by chance that congestion hit record peaks at the same time in Los Angeles – Long beach (LALB), and in the main ports in China, the two main poles of transpacific trade.

Clearly, LALB cannot handle the surge in imports, the arrival queue keeps on growing by the day (figure 11). There are now plans to shift to working 24/7. However, critics note that all this would do is to shift containers from ships to clog other already backlogged areas of the port, potentially reducing efficiency even further.

Meanwhile, in Shanghai and Ningbo there were also 154 ships waiting to unload at time of writing. The power-cuts seeing Chinese factories only operating 3-4 day weeks in many locations suggest a slow-down in the pace of goods accumulating at ports, but also imply disruption, shortages, and delays in loading, still making problems worse overall. Imagine large-scale US stimulus on top of a drop in supply!

Overall, “endemic congestion” is the perfect definition for the state of the global shipping market. It is the results of many factors: vessels cancellations and capacity control; Covid; bursts of demand in some trade lines; imbalances in container distribution; regular disruption in key arteries and ports; a backlog and increasing volumes cannot be dealt with at the same time, all creating an exponentially amplifying effect.

The epicenter is in the Pacific, but the problem is global. At present 10% of global container capacity is waiting to be unloaded on ship at the anchor outside some port. Solutions need to be found quickly – but can they be?

The Transpacific situation is particularly delicate, stemming from a high number of cancellations, ongoing disruption, and the highest demand surge in the global economy. However, this perfect recipe for a disaster is also affecting Asia–Europe lines where shipping rates hikes also do not show any signs of slowing down.

…and unstuck?

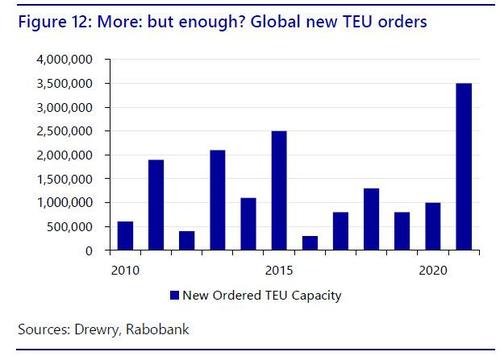

The shipping business would logically seem best-placed to get out of this situation by increasing vessel capacity. Indeed, orders of new ships spiked in 2021, and in coming years 2.5m TEUs will come on stream (figure 12). However, this will not arrive for some time, and may not sharply reduce shipping prices when it does.

Indeed, the industry –which historically operates on thin margins, and has seen many boom and bust cycles—knows all too well the old Greek phrase: “98 ships, 101 cargoes, profit; 101 ships, 98 cargoes, disaster”. They will want to preserve as much of the current profitability as possible, which a concentrated ‘Big 3’ makes easier.

Tellingly, a recent article stressed: “Ship-owners and financiers should avoid sinking money into new container vessels despite a global crunch because record orders have driven up prices, according to industry insiders.”

True, CMA CGM just froze shipping spot rates until February 2022, joining Hapag-Lloyd. Yet in both cases the new implied benchmark is of price freezes at what were once unthinkable levels – not price falls.

To conclude, shipping prices are arguably very high for structural reasons, and are likely to stay high ahead – if those structures do not change. On which, we even need to look at the structure of ships themselves.

Too Big to Sail

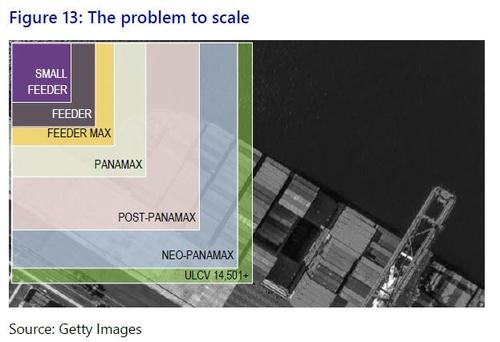

Shipping, like much else, has become much larger over the years. Small feeder ships of up to 1,000TEU are dwarfed by the largest Ultra-Large Container Vessels (ULCVs), which start from 14,501 TEUS up, and are larger than the US Navy’s aircraft carriers.

Of course, there is a reason for this gigantism: economy of scale. It is a sound argument. However, the same was said in other industries where painful experience, after the fact, has shown such commercial logic is not the best template for systemic stability. In banking we are aware of the phenomenon, and danger, of “Too Big to Fail”. In shipping, ULCVs and their associated industry patterns could perhaps be seen as representing “Too Big to Sail”.

After all, there are downsides to so much topside beyond the obvious incident with the Ever Given earlier in the year:

ULVCs cannot fit through the Panama Canal;

Not all ports can handle ULCVs;

They are slow at sea;

They are slow to load and unload;

They require more complex cargo placement / handling;

They force carriers to maximize efficiency to cover costs;

They force all in-land logistics to adapt to their scale;

They force a hub-and-spokes global trade model; and

They are vulnerable to accident or disruption, i.e., they were designed for an entirely peaceful shipping environment at a time of rising geopolitical tensions (which we will return to later).

In short, current ULCV hub-and-spokes trade models are the antithesis of a nimble, distributed, flexible, resilient system, and actually help create and exacerbate the cascading supply-chain failures we are currently experiencing.

However, we do not have a global shipping regulator to order shippers to change their commercial practices!

Specifically, building ULVCs takes time, and shipyard capacity is more limited.

As shown, the issue is not so much a lack of ULCVs, but limited capacity from ports onwards. That means we need to expand ports, which is a far slower and more difficult process than adding new containers or ships, given the constraints of geography, and the layers of local and international planning and politics involved in such developments. There is also then a need for matching warehousing, roads, trucks, truckers, rail, and retailer warehousing, etc. As we already see today, just finding truckers is already a huge issue in many economies.

Meanwhile, any incident that impacts on a ULCV port –a Covid lockdown, a weather event, power-cuts, or a physical action– exacerbates feedback loops of supply-chain disruption more than any one, or several, smaller ports servicing smaller feeder ships would do.

So why are we not adapting? Economic thinking, partly dictated by the need to survive in a tough industry; massive sunk costs; and equally massive vested interests – which we can collectively call “Too Big to Sail”. Naturally, some parties do not wish to move to a nimbler, less concentrated, more widely-distributed, locally-produced, more resilient supply-chain system –with lower economies of scale– while some

do: and this is ultimately a political stand-off.

Crucially, nobody is going to make much-needed new investments in maritime logistics until they know what the future map of global production looks like. Post-Covid, do we still make most things in China, or will it be back in the US, EU, and Japan – or India, etc.? Are we Building Back Better? Where?

Resolving that will help resolve our shipping problems: but it will of course create lots of new ones while doing so.

Tidal Wave of Politics

Against this backdrop, is it any surprise that a tsunami of politics could soon sweep over global shipping?

In July, US President Biden introduced Executive Order 14036, “Promoting Competition in the American Economy”. This puts forward initiatives for federal agencies to establish policies to address corporate consolidation and decreased competition – which will include shipping. Ironically, the US encouraged “Too Big to Sail” for decades, but real and political tides both turn.

Indeed, in August a bipartisan bill was introduced in Congress –“The Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 2021”– which proposes radical changes to:

Establish reciprocal trade to promote US exports as part of the Federal Maritime Commission’s (FMC) mission;

Require ocean carriers to adhere to minimum service standards that meet the public interest, reflecting best practices in the global shipping industry;

Require ocean carriers or marine terminal operators to certify that any late fees –known in maritime parlance as “detention and demurrage” charges– comply with federal regulations or face penalties;

Potentially eliminate “demurrage” charges for importers;

Prohibit ocean carriers from declining opportunities for US exports unreasonably, as determined by the FMC in new required rulemaking;

Require ocean common carriers to report to the FMC each calendar quarter on total import/export tonnage and TEUs (loaded/empty) per vessel that makes port in the US; and

Authorizes the FMC to self-initiate investigations of ocean common carrier’s business practices and apply enforcement measures, as appropriate.

Promoting reciprocal US trade would either slow global trade flows dramatically and/or force more US goods production. While that would help address the global container imbalance, it would also unbalance our economic and financial architecture. Fining carriers who refuse to pick up US exports would also rock many boats.

Moreover, forcing carriers to carry the cost of demurrage would change shipping market dynamics hugely. At the moment, the profits of the shipping snarl sit with carriers and ports, and the rising costs with importers: the US wants to reverse that status quo.

While global carriers and US ports obviously say this bill is “doomed to fail”, and will promote a “protectionist race to the bottom”, it is bipartisan, and has been endorsed by a large number of US organisations, agricultural producers and retailers.

Even smaller global players are responding similarly. For example, Thailand is considering re-launching a national shipping carrier to help support its economic growth: will others follow suite ahead?

Meanwhile, shipping will also be impacted by another political decision – the planned green energy transition. The EU will tax carbon in shipping from 2023, and new vessels will need to be built. For what presumed global trade map, as we just asked?

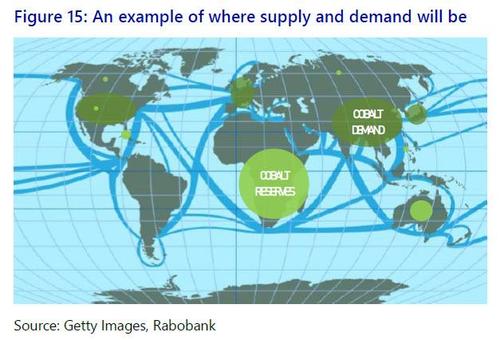

The green transition will also see a huge increase in the demand for resources such as cobalt, lithium, and rare earths. Economies that lack these, e.g., Japan and the EU, will need to import them from locations such as Africa and Australia. That will require new infrastructure, new ports, and new shipping routes – which is also geopolitical.

Indeed, the US, China, the EU, UK, and Japan have all made clear that they wish to hold commanding positions in new green value chains – yet not all will be able to do so if resources are limited. Therefore, green shipping threatens to be a zero-sum game akin to the 19th century scramble for resources. As Foreign Affairs noted back in July: “Electricity is the new oil” – meant in terms of ugly power politics, not more beautiful power production.

Before the green transition, energy prices are soaring (see our “Gasflation” report). On one hand, this may lift bulk shipping rates; on another, we again see the need for resilient supply chains, in which shipping plays a key role.

In short, current zero-sum supply-chains snarls, already seeing a growing backlash, are soon likely to be matched by a zero-sum shift to new green industrial technologies and related raw materials. In both dimensions, shipping will become as (geo)political as it is logistical.

Notably, while tides may be turning, we can’t ‘just’ reshape the global shipping system, or get from “just in time” to “just in case”, or to a more localized “just for me” just like that: it will just get messy in the process.

Cold War Icebergs

The US is now pushing “extreme competition” between “liberal democracy and autocracy”; China counters that US hegemony is over. For both, part of this will run through global shipping. Both giants are happy to decouple supply chains from the other where it benefits them. However, the larger geostrategic implications are even more significant.

Piracy and national/imperial exclusion zones used to be maritime problems, but post-WW2, the US Navy has kept the seas safe and open to trade for all carriers equally. This duty is extremely expensive, and will get more so as new ships have to be built to replace an ageing fleet. Meanwhile, China is building its own navy at breath-taking speed, and a maritime Belt and Road (BRI). As a result, a clear shift has occurred in US maritime strategy:

2007’s “A Co-operative Strategy for 21st Century Sea Power”, stressed: “We believe that preventing wars is as important as winning wars.”

2015’s update argued: “Our responsibility to the American people dictates an efficient use of our fiscal resources.”

2020’s title was changed to “Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power”, and stressed: “…the rules-based international order is once again under assault. We must prepare as a unified Naval Service to ensure that we are equal to the challenge.”

The US is also pressing ahead with the AUKUS defence alliance and the ‘Quad’ of Japan, India, and Australia to maintain naval superiority in the Indo-Pacific. This is generating geopolitical frictions, and fears of further escalation of maritime clashes in the region. The Quad has also agreed to key tech and supply-chain cooperation, with Australia a key part of a new green minerals strategy – a race in which China is still well ahead, and the EU lags.

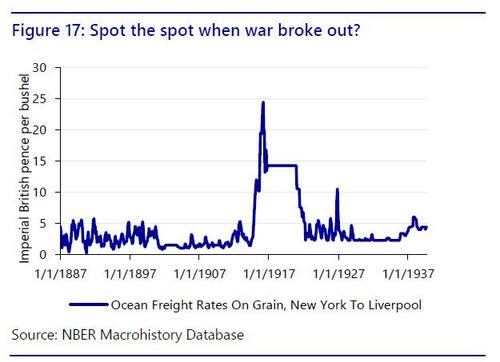

Should any kind of major incident occur, shipping costs would escalate enormously, as can easily be seen in the case of US-UK shipping from 1887-1939: this leaped 1,600% during WW1, and these shipping data stopped entirely in September 1939 due to WW2.

Crucially, US naval strategy is rooted in the post-WW2 power structure in which it benefitted from such control commercially. That architecture is crumbling – and there is a matching US consensus to shift towards “America First”, or “Made in America”. The thought progression from here is surely: “Why are we paying to protect shipping from China, or economies that do not support us against China?”

In short, the strategic and financial logic is: surrender control of the seas, or ensure commercial gains from it.

There are enormous implications for shipping if such a shift in thinking were to occur – and such discussions are already taking place. July 2020’s “Hidden Harbours: China’s State-backed Shipping Industry” from the Center for Strategic and International Studies argued:

“The time is long overdue for the US to reinvigorate its maritime industries and challenge the Chinese in the same game by using the very same techniques the Chinese have used to gain dominance in the global maritime industry.

The private-sector maritime industry cannot do this alone—the US maritime industry simply cannot compete against the power of the Chinese state.

The US and allied governments must bring to bear substantial and sustained political action, policies, and financial support. To do anything less is to cede control of the world’s maritime industry and global supply chains to China, and perhaps to force the US and its allies to enter their own ‘century of shame.’”

Meanwhile, stories link ports and shipping to national security (see here and here), underlining logistics are no longer seen as purely commercial areas, but rather fall within the “grey zone” between war and peace – as was the case pre-WW2. This again has major implications for the shipping business.

Expect that trend to continue ahead if the maritime past as guide, as we shall now explore.

The Ship of Things to Come?

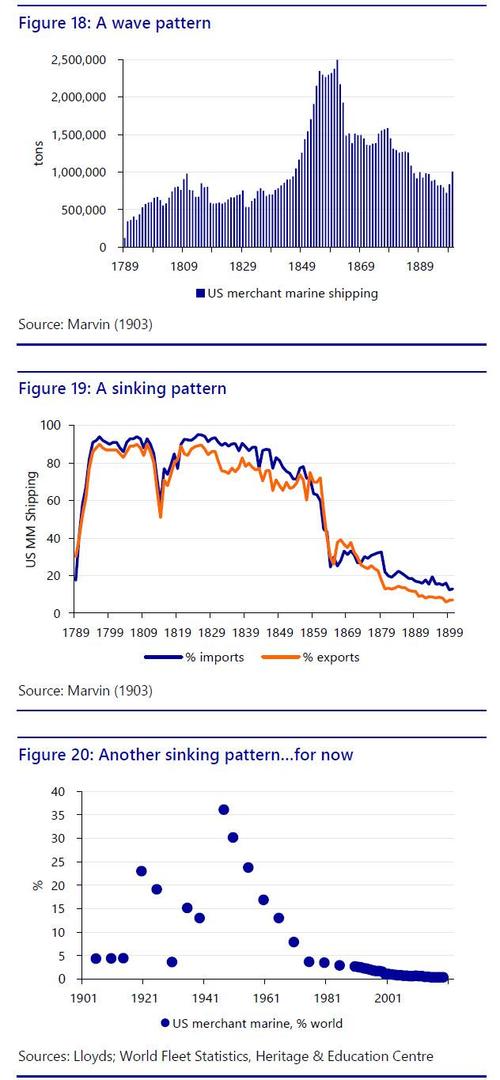

US maritime history in particular holds some clear lessons for today’s shipping world if looked at carefully.

First, the importance of the sea to what we now think of as a land-based US: the US merchant marine helped it win independence from the powerful naval forces of the British, and the first piece of legislation Congress passed in 1789 was a 10% tariff on British imports, both to build US industry and merchant shipping.

Indeed, the underlying message of US maritime history is that the US is a major commercial force at sea – but only when it sees this as a national-security goal.

Following independence, US commercial shipping and industry surged in tandem, with an understandable dip only due to war with the British in 1812. The gradual normalisation of maritime trade with the UK after that saw a gradual decline in the share of trade US shipping carried, which accelerated with the end of steamship subsidies –which the British maintained– and the US Civil War.

By the start of the 20th century, W. L. Marvin was arguing: “A nation which is reaching out for the commercial mastery of the world cannot long suffer nine-tenths of its ocean-carrying to be monopolized by its foreign rivals.” Yet 1915 saw the welfare-focused US Seaman’s Act passed and US flags move to Panama, where costs were lower. However, WW1 saw US shipping surge, and the Jones Act in 1920 reaffirmed ‘cabotage’ – only US flagged and crewed vessels can trade cargo between US ports.

The 1930s saw global trade and the US maritime marine dwindle again – until 1936, when the Federal Maritime Commission was set up “to promote the commerce of the US, and to aid in the national defense.” WW2 then saw US mass production of Liberty Ships account for over a third of global merchant shipping – and then post-1945, this lead slipped away again, and the US merchant marine now stands at around just 0.4% of the world fleet.

Indeed, in 2020, US sealift capability was reported short on personnel, hulls, and strategy such that the commercial fleet would be unlikely to meet the Pentagon’s needs for a large-scale troop build-up overseas. As we see, the US has been here several times before. If the past is any guide for the future response, this suggests the following US actions could be seen ahead:

Use its market size to force shippers to change pricing – which may already be happening;

Raise tariffs again (on green grounds?);

Refuse to take goods from some foreign ships or ports;

Force vessels to re-flag in the US, at higher cost;

Build a rival to China’s marine BRI with allies;

Massive ship-building, for the 3rd time in the last century;

Charter US private firms to bring in green materials; or

The US Navy stops protecting some sea lanes/carriers, or forces the costs of their patrols onto others.

It goes without saying that any of these steps would have enormous implications for global shipping and the global economy – and yet most of them are compatible with both the strategic military/commercial logic previously underlined, as well as the lessons of history.

Wait and Sea?

We summarize what we have shown in the key points below:

Markets

For markets, there are obvious implications for inflation. How can it stay low if imported prices stay high? How will central banks respond? Rate hikes won’t help. Neither will loose monetary policy – and less it is directed to a directly-related government response on supply chains and logistics.

This suggests greater impetus for a shift to more localised production on cost grounds, at least at the lower end of the value chain, if not the more-desirable higher end. Yet once this wave starts to build, it may be hard to stop. Look at EU plans for strategic autonomy in semiconductors, for example, which are echoed in the US, China, and Japan.

For FX, the countries that ride that wave best will float; the ones that don’t will sink.

Helicopter view of ships

Clearly, shipping will continue to boom. There are huge opportunities in capex on ships, ports, logistics, and infrastructure ahead – as well as in new production and supply chains. Yet one first needs to be sure what, or whose, map of production will be used for them!

As the industry sits and waits for the wind and tide to change, logically one wants to position oneself best for what may be coming next. That implies global consolidation and/or vertical integration: Large shippers looking at smaller shippers to snuff out alternative routes and capacity; shippers looking at ports; ports looking at shippers; giant retailers/producers looking at shippers; importers banding together for negotiating power in ultra-tight markets. Of course, nationally, governments are looking at shippers, or at starting new carriers.

If this is to be a realpolitik power struggle for who rules the waves –“Too Big to Sail”, or a new more national/resilient map of production– then having greater scale now increases your fire-power. Of course, it also makes you a larger target for others.

Let’s presume current trends continue. Could we even end up with a return to older patterns of production, e.g., where oil used to be produced by company X, refined in its facilities, shipped on its vessels, to its de facto ports, and on to its retail distribution network. Might we even see the same for consumer goods? That is the logic of globalisation and geopolitics, as well as the accumulation of capital.

However, if history is a guide, and (geo)politics is a tsunami, things will look very different on both the surface and at the deepest depths of the shipping industry and the global economy. Much we take as normal today could become flotsam and jetsam.

To conclude, who benefits from the huge profits of the current shipping snarl, and who will pay the costs, is ultimately a (geo)political issue, not a market one.

Many ports are likely going to be caught up in that storm.