For over a year, we have been dutifully tracking several key datasets within the auto sector to find the critical inflection point in this perhaps most leading of economic indicators which will presage not only a crushing auto loan crisis, but also signal the arrival of a full-blown recession, one which even the NBER won’t be able to ignore, as the US consumers are once again tapped out. A month ago we said that in our view “that moment has now arrived”; the latest data from Fitch confirms as much.

But first, for those readers who are unfamiliar with the space, we urge you to read some of our recent articles on the topic of car prices – which alongside housing, has been the biggest driver of inflation in the past 18 months – and more specifically how these are funded by the US middle class, i.e., car loans, and last but not least, the interest rate paid for said loans. Here are a few places to start:

- Are We Headed For An “Auto Loan Crisis” As Delinquencies Begin To Rise? – July 7

- A Flood Of Repossessed Vehicles Poised To Hit The Used-Car Market – July 25

- American Drivers Go Deeper Into Debt As Inflation Pushes Car Loans To Record Highs – Aug 29

- Credit Card Rates Just Hit A Record As The Average Car Loan Rises To Fresh All Time High – Oct 9

- New-Car Loan-Rates Set To Hit 14-Year High As Affordability Crisis Worsens – Nov 3

- Perfect Storm Arrives: “Massive Wave” Of Car Repossessions And Loan Defaults To Trigger Auto Market Disaster, Cripple US Economy – Dec 18

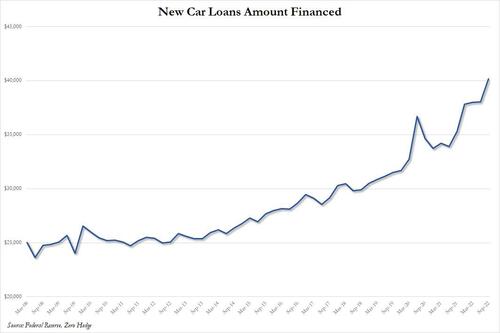

So while the big picture is clear – Americans are using ever more debt to fund record new car prices – fast-forwarding to today, we have observed two ominous new developments: the latest consumer credit report from the Fed revealed a dramatic spike in the amount of new car loans, which increased by more than $2,000 in one quarter, from just over $38,000 (a record), to $40,155 (a new record).

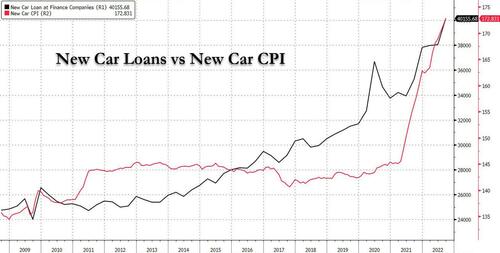

Now this shouldn’t come as a shock: a simple reason why new car loans have hit record highs is simply because new car prices have also soared to all time highs, as the next chart shows.

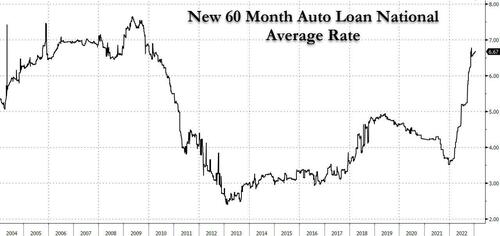

Here we will ignore for the time being cause and effect, or “chicken or egg” questions – i.e., whether record new car prices are the result of easy record credit, or whether record new car loans are simply tracking the explosive surge in car prices, and instead focus on something even more ominous: the explosion in the average interest rate on a new 60 month auto loans: according to Bankrate, as of Jan 27, the number is just over 6.67%, almost doubling since the start of 2022, and the highest in 12 years.

It is this surge in nominal auto debt as well as the unprecedented spike in new auto loan rates, that we believe has finally pushed the US car sector to the infamous Wile Coyote point of no return.

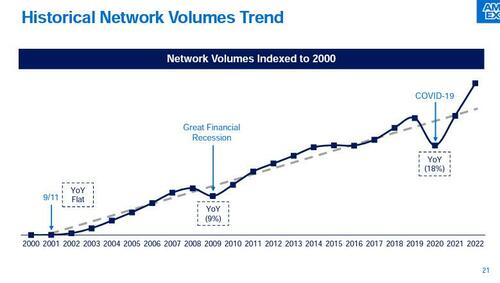

But first lets back up a bit. Recall, on Friday American Express reported blowout earnings, and forecast that revenue and earnings for 2023 will surge well above what analysts estimated after the company saw customer spending on its cards soar to a record in the final three months of the year, a time when the US economy was rapidly sliding into contraction.

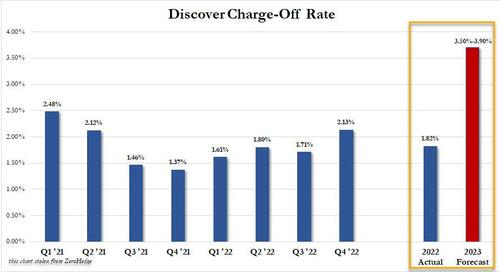

This is hardly a shock: targeting mostly the wealthiest tier of U.S. society, the future is bright for AmEx and its customers who – let’s face it – are not seeing a huge hit to their standard of living as a result of soaring prices and interest rates. It is everyone else that is getting hit hard, and it is everyone else that is using cards like Capital One and Discover (which target FICO score about 40-60 lower than AmEx). And readers will recall that it was Discover which two weeks reported that its projected charge off rate for 2023 would more than double from its current 1.82% to as much as 3.90%!

The news hit the stock like a lead balloon, and sparked renewed fears that the bottom and middle-classes are already in recession.

Then again, for those keeping a tab on the latest development in the US car market – where the bulk of consumers use Discover, not AmEx – that’s not exactly a shock.

Consider the following: as we first reported a month ago, a soaring number of consumers are falling behind on their car payments – a trend which will only accelerate – in a sign of the strain soaring car prices and prolonged inflation are having on household budgets.

Citing a NBC report, we reported that whereas repossessions tumbled at the start of the pandemic when Americans got a boost from stimulus checks and lenders were more willing to accommodate those behind on their payments, in recent months, the number of people behind on their car payments has been approaching prepandemic levels, and for the lowest-income consumers, the rate of loan defaults is now exceeding where it was in 2019, according to a recent report from Fitch.

Fast forward to today, when a newer report from Fitch has laid out an even more startling milestone: more Americans are falling behind on their car payments than during the financial crisis. As Bloomberg first observed after skimming the Fitch note, in December the percentage of subprime auto borrowers who were at least 60 days late on their bills rose to 5.67%, up from a seven-year low of 2.58% in April 2021. That compares to 5.04% in January 2009, the peak during the Great Recession, and just a few weeks before the Fed was about to start QE1.

The result, Bloomberg reports extending on our observation from December, is that the number of car repossessions is soaring. Take the case of 21-year-old Kobe Hatch, who walked outside his Chicago home in December and couldn’t find his 2013 Dodge Journey; he immediately knew it had been repossessed for a simple reason: he hadn’t made the car payment months.

Without a car, Kobe couldn’t do his job as a delivery driver for Amazon and got fired. Now, he’s struggling to make his rent payments and can’t afford groceries, even with food stamps.

“It’s been very stressful for the past few months,” he said. “Inflation has really taken a toll on people.” And it certainly has, although that doesn’t explain why Kobe didn’t make his car payments in the first place. Maybe he should have bought a care he could – gasp – afford even in a worst-case scenario. He didn’t, but instead of blaming himself it is of course easier to blame inflation.

Hatch is part of a growing cohort of Americans facing auto repossessions, an ominous sign for the US economy. As we first explained in December, during the pandemic, a surge in used car prices forced buyers to take out bigger loans for their vehicles. The monthly payments seemed doable in an era of stimulus checks, a tight labor market and surging stocks, but that’s changed for many people as inflation eats into their budgets and the job market cools.

While few bothered to budget how they would pay for that new car purchased just one year ago at all time high prices, even fewer anticipated a world where spiking rates would make payment on the monthly auto payment virtually impossible. The average new auto loan rate was 8.02% in December, up from 5.15% a year earlier, according to Cox Automotive. The rate is usually much higher for subprime borrowers.

For Hatch, who is subprime, the total monthly bill for his car reached about $1,000, including the cost of insurance, thanks to a whopping 26% interest rate. Even if he can manage to save up enough to get the car back – about $1,100 for the repossession fee – there’s a strong chance he won’t be able to make the payments in subsequent months, especially now that he’s unemployed. Again, maybe Hatch should have bought a used clunker he could afford at the time and make a one time payment instead of diluting his future cash flow stream. Then again, there were iPhones to be bought and countless trinkets that were urgently in need of purchase by Hatch, who looked at that stimmy gravy train and assumed it would never end… well, oops. And in any case this is not an article about personal responsibility which in the US no longer exists but, well, economics 101.

And speaking of economics, the good news is that while the number of vehicle repossessions is still below pre-pandemic levels – at Manheim, the auto auction company, the number of repossessed cars increased 11% in 2022 compared to the prior year, which was still down 26% from 2019 – it is soaring fast and unless something major changes, it will soon overtake most recessionary benchmarks.

When exactly a lender can repossess a car varies by state, but it can happen in many cases as soon as a borrower is in default — often when a payment is not made on time, according to the Federal Trade Commission. Usually, though, it takes two or three consecutive missed payments for a repossession to happen. Once the vehicle is seized, the repossession can affect the borrower’s credit score for as long as it stays on the credit report, usually about seven years, according to Experian.

One such borrower is Josef Fields of Forth Worth, Texas: he, too, fell behind on his car payments and now faces a hit to his credit score. With his monthly bill at $556 for his 2021 Subaru WRX, the 25-year-old was having a hard time figuring out which costs to prioritize. He wouldn’t have such a hard time if instead of buying a car which according to carmax costs around $35K now, and cost even more new, had instead purchased, say, a 1998 Hyundai. But, again, this is sadly not an article about personal responsibility and Americans’ inability to budget for a downside case. So instead of settling for a cheaper car, Josef is now trying to apply for a hardship program through his bank, but it is too late: he too woke up to an empty driveway a week before Christmas.

Now, the repossession and tow fee will cost him $1,600 — about the total sum he owes in back payments as well. He’s trying to save up for another car but it will likely take a while (just a guess here, but his next car won’t be a 1998 Hyundai either, and it won’t be too long before it too is repossessed). One positive is that he can walk to his job at the local post office. But whenever he needs to go to the grocery store, he has to ask a friend or take an expensive Uber. We can only assume his net worth will have to get deeply negative before he discovers mass transport.

Fields is worried about how this will affect his financial future, especially his dream to buy a house one day (judging by his track record, any house Josef buys will be greatly overvalued and he will default shortly after). He estimates that the repossession shaved about 40 points off his credit score.

For some, however, the only lesson is to try and outsmart the repo man: hardly the best long-term strategy. Take San Antonio native Zhea Zarecor who is currently trying to negotiate with her lender so her 2013 Honda Fit won’t get repossessed. In the meantime, she’s hiding it.

The 53-year-old, who is currently in school for her bachelor’s in information technology (and raking up massive student loans for an education she should have had some 35 years ago) splits the monthly bill for the car — about $178 — with her roommate. But then the roommate lost his job, and with prices for groceries and everyday items increasing, there just wasn’t enough for the car payments.

Zarecor is trying to make extra money with odd jobs like contract secretarial work and participation in medical studies, but it often feels hopeless, she said. “Our money doesn’t go as far as it used to,” she said. “I don’t see prices going down, so the only relief I see is when I get my degree.”

* * *

So what happens next? Well, some, like Cox Automotive, remain optimistic: their analysts (who just may be a little conflicted) forecast that while loan defaults and repossessions will increase from their pandemic lows, long-term through 2025 they predict overall defaults and repossessions will remain at or below historic norms.

Still, the financial squeeze has been particularly difficult for lower-income consumers looking for budget vehicles, which have been particularly hard to find. While in the past, those car buyers would have purchased a used car for $7,000 to $15,000 they are now having to spend $20,000 to $25,000 for the same type of vehicle. Among dealers that cater to subprime and deep subprime consumers, the average listing price on their cars has almost doubled since the beginning of the pandemic, according to the CFPB.

“That near prime and subprime group of consumers, they’re getting hit very, very hard by inflation. That group of people did not have much disposable income. They had to finance a more expensive car and then they got hit with prices going up overall. There’s just a lot of stress,” said Kelly.

Ally Financial, which has a significant share of loans to subprime borrowers, said in its October earnings report that it expects delinquencies to increase to as much as 3.8% compared with 3.1% in 2019. One month ago we said that estimate will prove to be overly optimistic, and today we are getting further confirmation of our skepticism.

As twitter’s CarDealershipGuy – who claims to be an anonymous auto-industry CEO and whose analysis has been featured in places like the NY Post and who frequently Tweets about the state of the auto market – laid out a recent blog post, Capital One released its Q4’22 earnings on Tuesday. The company missed revenue targets ($9.04 billion instead of $9.07 billion) and reported a net income of $1.2 billion, which is half of what it was a year ago. Adjusted per-share earnings are at $2.82, which is significantly below analysts’ expectation of $3.87.

Along with other banks that are anticipating a downturn in the economy, Capital One has been bulking up their reserves for losses. Banks set aside these funds when credit quality begins to deteriorate, which occurs when past-due accounts or charge-offs start increasing. Capital One’s provision for credit losses increased $747 million to $2.4 billion, which is up $1.4 billion year over year.

One look at the auto lending section of the report, should answer why.

The trends I talked about in my previous newsletters (here and here), credit tightening and rising defaults are all evident. The net charge-off rate for auto loans was 1.7%, up from 0.6% last year. Auto loan originations were at $6.6 billion, down 20% year over year.

From what I see on my dealership floor, I believe that Capital One has taken the most drastic turn in tightening the credit, compared to Ally, Santander, and others.

Our volume with Capital One is down 50% quarter over quarter. To put it simply, we are not putting any business through Capital One because its offerings are not competitive anymore. It feels like the bank intentionally turned off the spigot with originations. Either it is preparing to face significant losses, or the company is just being extra cautious.

The anonymous auto dealer dug deeper and here is what he found out after speaking with a few insiders:

There’s a lot of internal turmoil happening inside the bank. In the words of the person familiar with the situation, never has there been so many high performers moved between divisions. Not just any divisions! Turns out that many leaders are moved from the dealer technology and products division to the “help me catch up” division. This division’s purpose is to work with delinquent customers.

This department has been largely neglected in the past, so why would Capital One suddenly decide to stifle innovation and reshuffle its workforce?

I see it as another affirmation of what to expect from the market in the coming year. Significantly propping the services division by the top automotive lender tells me that delinquencies are rising as consumers are struggling to manage their auto loan payments.

Cox Automotive’s data also supports my thinking: auto loan performance in December deteriorated with loans delinquent by more than 60 days increased by 5.3% and were up 26.7% from a year ago.

Finally, while the existing loan pipeline is bracing for soaring delinquencies and default and catastrophic writedowns, new loan originations have collapsed not only because of higher loan standards but because most Americans suddenly realize they can’t afford monthly payments at these rates. “I dare think what happens to people who are signing up for new loans today,” said Ivan Drury, director of insights at car buying website Edmunds. “It’s not going to be better when we see these payments so high.”

As for the repo men, now that is one industry that will be booming all throughout the coming recession. “These repossessions are occurring on people who could afford that $500 or $600 a month payment two years ago, but now everything else in their life is more expensive,” said Drury, “That’s where we’re starting to see the repossessions happen because it’s just everything else starting to pin you down.”

Indeed, for those in the repossession business, it’s been almost impossible to keep up with the surge in, well, “new business.” Jeremy Cross, the president of International Recovery Systems in Pennsylvania, said he can’t find enough repo men to meet the demand or space to hold all the cars his company has been tasked with repossessing. With the holidays approaching, he’s been particularly busy as people prioritize spending elsewhere, and he’s expecting business to keep up throughout next year and 2024.

“Right now, it’s really the perfect storm,” said Cross. “Over the last two years, vehicle prices were inflated because there was no new car supply, people were still buying like crazy because they had a lot of stay-at-home cash, they had inflated credit scores, so it was like a recipe for disaster.”