The root causes of the economic upheaval most Americans are experiencing right now are the subject of much discussion lately. Is it the Russia-Ukraine conflict? Is it Biden’s closing of the Keystone XL pipeline? Is it the absurd energy policies of the EU? Certainly there is plenty of blame to go around, but the reality is that all of this started in October of 2020. Back then, Trump and Biden were going head to head in debates leading up to the November election. Biden famously stated “I would transition away from the oil industry.”

That statement was a clear signal to energy producers in this country that Biden’s eventual ascent to the presidency would bring unprecedented uncertainty for at least the next four years. Never willing to let a crisis go to waste, the Biden administration went straight to work dismantling the future of our oil and gas refining capacity. His statement in October of 2020 made it clear that his administration would use the massive increase in government control precipitated by the pandemic to massively curtail energy production not in the distant future, but here and now.

Though oil production has rebounded to some extent from the demand-driven crash in 2020, refining and drilling are still well below pre-pandemic levels. The regulatory uncertainty imposed on traditional energy production is simply too great. Biden can complain that these companies aren’t throwing money away to save his poll numbers, but a lifetime politician like him is in no place to criticize those who provide essential goods and services to the American public. Biden’s insistence that his policies have no role in the pain Americans feel right now should fall on deaf ears.

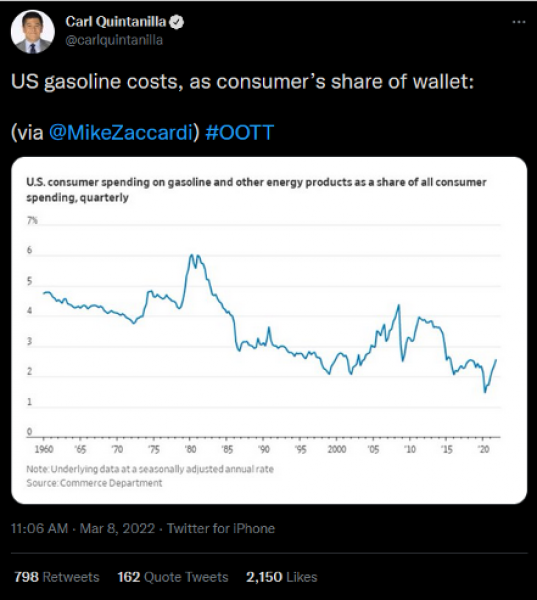

So just how severe is this pain? Carl Quintanilla of CNBC’s “Squawk on the Street” shared this graph in a tweet on March 8th in an apparent attempt to put a damper on concerns about gasoline prices. Quintanilla states that the graph represents “gasoline costs, as consumer’s share of wallet” but that’s not entirely correct. For one, the graph clearly states that it takes account of other energy products and that it is computed as a share of “all consumer spending.”

His intended point is obvious enough: Americans shouldn’t complain about high gas prices because, as a share of total spending, gasoline is very low by historical standards. Quintanilla’s comment sounds like the author of the graph added up all the money spent on the various things we buy and compared the dollars spent on fuel to the total. That’s not the case.

A much better representation of the impact on Americans’ wallets would include information about the astronomical inflation we’ve seen in other essential products Americans buy. It would also have a concrete measure of the “wallet” Quintanilla mentions.

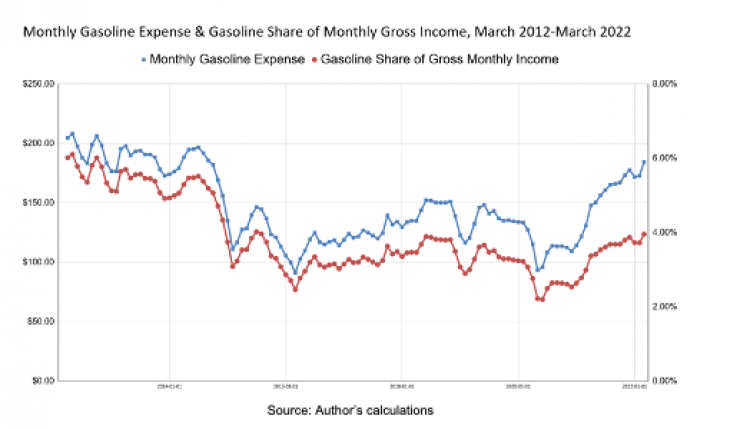

The graph below uses data on average production and non-supervisory hourly wages over the past ten years as a baseline gross monthly income. The most recent data available indicates that the average wage for such workers is $26.94 per hour. I assumed that the household drove about 250 miles a week in a car with 20 miles per gallon average fuel efficiency. The blue line shows monthly gasoline expense based on these assumptions using data on conventional gasoline prices. So without regard to income and other expenses Americans have to cover, we are paying about the same now as we were during the high gas price era of Obama’s second term: just under $200 per month.

But what about the total household budget? Haven’t wages risen over the past ten years, making the increased expense less onerous? Production and non-supervisory wages have risen steadily from 2012 to 2022 to the tune of about 3.75% per year. Dividing the monthly gasoline expense by gross monthly income, we get the red line. During the Trump administration, gasoline as a share of income was right around 3.25% of the budget, according to my simple calculations. In 2021, it began to rise again and currently sits as high as it has been for the past 6 years.

Those who are sympathetic to Quintanilla’s point might say that we have validated the graph in his tweet, that American’s aren’t as bad off as many claim. However, this analysis misses the rising cost of nearly everything else in Americans’ household budgets. Starting in mid-2021, prices of staple goods began to skyrocket. The most recent report shows that, compared to this time last year, food and beverage prices rose 7.6%, durable goods prices (such as appliances and cars) rose 18.7%, and overall energy prices rose 25.6%.

Inflation is too much money chasing too few goods. While the Federal Reserve contemplates decreases in the money supply to deal with the money component, the Biden administration’s regulatory chaos continues to restrict our ability to produce the things Americans need. Blaming inflation on the Ukraine-Russia conflict, which is also partly his fault, does nothing to alleviate the stranglehold Biden has on our economy.

Levi A. Russell, PhD, is an Assistant Teaching Professor in the School of Business at the University of Kansas.