By John Kemp, Reuters energy reporter Europe’s rising energy prices will force factory closures

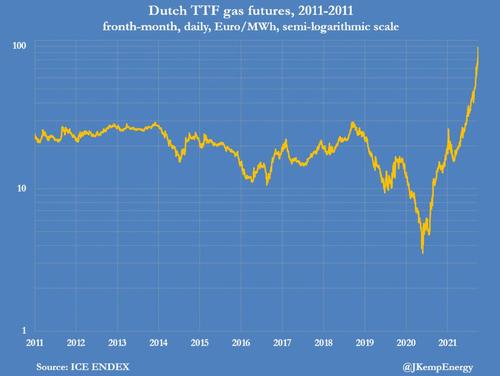

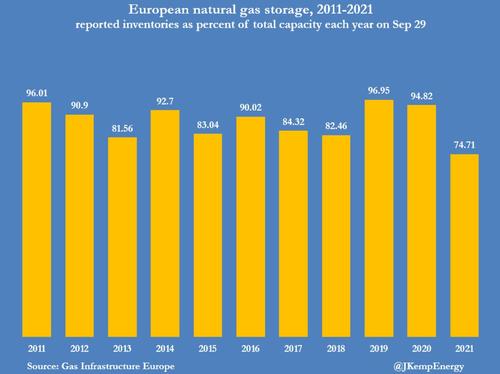

Europe’s increasingly expensive gas and electricity prices are sending a strong signal to manufacturers to consider temporary plant closures and to home and office owners to turn down thermostats to conserve fuel this winter. Front-month gas futures are now more than six times more expensive than at this point last year, as the region struggles to import enough gas to refill its depleted storage ahead of the winter peak heating season.

Regional storage sites are still only 74.7% full, the lowest for more than a decade, and compared with a pre-pandemic five-year seasonal average of 87.4%, according to Gas Infrastructure Europe.

In the short term, Europe is unlikely to attract significantly more gas because production is fixed and there is already a worldwide shortage, which is also pushing up prices in Northeast Asia and North America.

Escalating futures prices signal traders think lower consumption will be necessary to prevent stocks eroding to critically low levels and risking fuel supplies running out this winter. Rising prices will find the path of least-resistance to cut consumption – with the most price-sensitive and least politically sensitive customers forced to reduce gas and electricity use first and most deeply.

In theory, the crisis could be resolved easily by homes, offices, schools and factories turning down thermostats by 0.5-1.0 degrees this winter; the result would be an enormous fuel saving with only a minimal impact on comfort.

In practice, policymakers will be reluctant to call for thermostat reductions since it implies a policy failure and has unpopular associations with one-term U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

European governments are instead trying to shield residential and small business customers from the full force of increasing energy prices on utility bills through price caps, rebates and tax cuts. But if the crisis continues to worsen, and especially if the winter proves colder than normal, shielding residential customers could prove unsustainable and calls for energy conservation may become inevitable.

In the meantime, policymakers are likely to explore other fuel saving measures, including reduced street-lighting and extended closures of government buildings, offices and schools over the mid-winter holiday period.

More significant savings could be made if manufacturers close their operations temporarily, cutting consumption and potentially reselling energy into the spot market if they have already contracted to buy it. Steeply rising energy costs will force many manufacturers to reassess their production plans this winter, especially those with energy-intensive processes and/or limited ability to raise the price of their own products.

For manufacturers, short closures have the double benefit of cutting energy costs and also driving up the price of their products, helping protect margins against rising power and gas prices.

Once enough credible plant closures and other energy-saving measures are announced futures prices are likely to moderate. Plant closures would, however, worsen problems throughout the supply chain and intensify the upward pressure on inflation, as well as disrupting long-standing customer relationships.

But unless the winter proves mild, price rises and physical shortages of gas, coal and electricity are unlikely to remain confined to energy markets, rippling out to the rest of the economy as is already happening in China