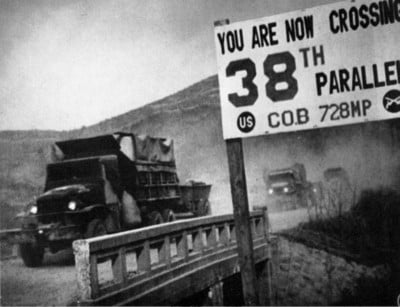

As the time-honored saying goes, ‘It ain’t what you know that gets you in trouble, it’s what you know that ain’t so.’ If Americans ‘know’ anything about Korea, it is that the North Koreans started the Korean War in 1950 when they invaded South Korea across the 38thParallel, and that after three years of fighting the boundary again settled on that same line. The reality of the conflict between North and South Korea is much more complex and much more interesting than that simplistic tale.

A good starting point for understanding the ongoing conflict between North and South Korea is the agreement between the United States and Japan in 1905, known as the Taft-Katsura Memorandum, which was signed as Japan was defeating Russia in the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War. In that document the U.S. agreed to the Japanese colonization of Korea in trade for the American occupation of Hawaii (which the U.S. had annexed in 1898) and the Philippines (which the U.S. had acquired as booty in 1898 at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War). Koreans were not consulted about this arrangement.

In 1910 Japan annexed Korea, making it a subservient colony of the homeland; this had also been sanctioned by the U.S. In the Taft-Katsura Memorandum five years previously. Japanese rule was brutal: it is estimated that at least 18,000 Koreans were killed due to resisting the occupation. Koreans were forced to take Japanese names and speak only Japanese, young Korean males were impressed into the military and sent to Japan to work for slave wages, and tens of thousands of young Korean women were forced into sexually slavery for the pleasure of Japanese males.

Not surprisingly, when Japan surrendered to the U.S. and its allies on August 15, 1945, Koreans were elated at this apparent liberation from Japanese oppression. They were ready and willing to form their own government: a quickly formed Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence (CPKI) organized people’s committees throughout the country to coordinate the transition to independence. On August 28, 1945 the CPKI announced that it would function as the temporary national government of Korea. On September 6th delegates from throughout Korea, both north and south of the artificially imposed demarcation line gathered in Seoul to create the Korean People’s Republic of Korea (PRK). Coincidentally, the Koreans announcement of their unified independence came only four days after Ho Chi Minh’s declaration of a unified independence for all of Vietnam.

The United States had a different plan for Korea. At the February 1945 Yalta conference, President Roosevelt suggested to Stalin, without consulting the Koreans, that Korea should be placed under joint trusteeship following the war before being granted her independence. On August 11, two days after the second atomic bomb was dropped assuring Japan’s imminent surrender, and three days after Russian forces entered Manchuria and Korea to oust the Japanese as was agreed to avoid further U.S. casualties, Truman hurriedly ordered his War Department to choose a dividing line for Korea. Two young colonels were given 30 minutes to resolve the matter. The 38th parallel was quickly chosen. Surprisingly, Stalin agreed to this “temporary” partition. On August 15, the United States Army Military Government in Korea was formed and on September 8, 72,000 U.S. troops began arriving to enforce the formal occupation of the south.

General Douglas MacArthur, as commander of the victorious Allied powers in the Pacific, formally issued a proclamation addressed “To the People of Korea,” announcing that forces under his command “will today occupy the territory of Korea south of 38 degrees north latitude.” Ironically Korea, which was a non-aggressor during WWII and throughout history, was now divided, while Japan remained intact.

The U.S. understood that if it was to assert Western-style, capitalist control in Korea it had to defeat, then eliminate, the broad-based popular, democratic and socialist-leaning KPR. Instead of repatriating Japanese as mandated, the U.S. military government, manned by 2,000 U.S. officers, most of whom were unable to speak or understand the Korean language, quickly recruited them and their Korean collaborators to continue administrative functions. Equally egregiously, the U.S. military government revived the feared Japanese colonial police force, the Korean National Police (KNP). About 85 percent of the Koreans who had served in the Japanese colonial police force were quickly employed by the U.S. to man the KNP.

The U.S. hurriedly organized wealthy conservative Koreans representing the traditional land-owning elite and, on September 16, convened the Korean Democratic Party (KDP). The U.S. had quickly identified “several hundred conservatives” among the older and more educated Koreans who had served the Japanese who could serve as the nucleus for the rapidly convened KDP. These were the Koreans who had grown wealthy as a result of years of collaboration with their Japanese colonizers.

On October 12th the U.S. flew the Korean-American Syngman Rhee in from Washington D.C.–where he had lived for the past 40 years–to Seoul to head this new government. On December 12, 1945, the U.S military government outlawed the KPR and all its related local, provincial and national democratic peoples’ organizations and activities, including all labor unions. Had the KPR been able to proceed with their plan of a united Korea, it is almost certain that the communist Kim Il-sung would have been elected president over a united Korea, (just as Ho Chi Minh would have won had elections been held in divided Vietnam in 1956), as he had spent the previous 10 years leading guerrilla actions against the occupying Japanese and was widely popular.

In the newly created South Korea a large-scale resistance movement arose against the U.S. military and its appointed puppet Korean government. In September 1946 a workers strike spread throughout the country, which was then forcefully suppressed by the new Republic of Korea Army (ROKA) and the U.S. military. At least 1,000 Koreans were killed with more than 30,000 jailed. Regional and local leaders of the popular movement were now either dead, in prison, or had gone underground.

On March 1, 1948, a large nonviolent demonstration on Korea’s Jeju Island took place to celebrate the anniversary of the Korean people’s 1919 mass demonstrations against Japanese occupation. Using the occasion to protest Rhee’s planned separate elections scheduled for May 1948, the crowd was fired upon by the Korean National Police. The police arrested 2,500, a number were injured, and several Koreans were tortured, then killed. The March 1 incident provoked a larger people’s rebellion that erupted on the island on April 3. Rhee was in fact elected president on July 20, 1948 in a farsical election in which only the nation’s elite participated.

The U.S. military commander on Jeju, Colonel Rothwell Brown, ordered an indiscriminate scorched earth campaign as the Jeju uprising escalated. The U.S. Navy blockaded the island with eighteen warships, while bombarding it with 37mm cannons. U.S. planes conducted regular reconnaissance missions and dropped grenades and bombs.

Korean army units from the southern port city of Yosu were ordered to Jeju to put down the resistance and they rebelled, refusing to go. This mutinous rebellion quickly spread to other areas in the southern part of the mainland. Within two weeks this mutiny was contained by a brutal campaign coordinated by U.S. military adviser Captain James Hausman and carried out with the aid of U.S. aircraft, firepower, and ground troops. All Koreans suspected or those thought sympathetic with the uprising were executed.

The Jeju insurgency was crushed by August, 1949, with repression growing in its sadistic dimensions. Suspects were often stripped naked, tortured, forced to have sex before being beheaded while loved ones were forced, first to watch while clapping with their hands, then to parade in front of their torturers carrying the severed heads of family members. Sexual perversity and military violence are common companions; just ask any soldier. An estimated 60,000 residents of the island were killed by South Korean and U.S. forces, with another 40,000 fleeing abroad.

A guerrilla movement against the US military/Syngman Rhee government spread throughout South Korea, and lasted until the end of the war in 1953. The government used its military superiority to incarcerate several hundred thousand Koreans who had—or might even conceivably have had—any socialist or communist sympathies. Massive numbers of farmers, villagers and urban residents were systematically rounded up in rural areas, villages and cities from throughout South Korea. Captives were regularly tortured to extract names of others. Thousands were imprisoned, and even more thousands forced to dig mass graves before being ordered into them and shot by fellow Koreans, often under the watch of U.S. officers. Estimates of civilians murdered under the pretext of killing “communists” during the era of legal U.S. occupation (August 15, 1945-August 15, 1948) and the succeeding extended period until June 30, 1949 when U.S. combat troops were finally withdrawn, are in the 500,000 range. Nobody knows for sure because no records were kept and facts about this slaughter was forcefully concealed for 40 years.

Through the postwar decades of South Korean right-wing dictatorships, victims’ fearful families kept silent about that blood-soaked summer. American military reports of the South Korean slaughter were stamped “secret” and filed away in Washington. Communist accounts were dismissed as lies. Only since the 1990s, and South Korea’s democratization, has the truth begun to seep out. In 2002, a typhoon’s fury uncovered one mass grave. Another was found by a television news team that broke into a sealed mine.

North & South Korea increasingly clashed across the 38th parallel before the onset of war. The North Korean government claimed that in 1949 alone, the South Korean army and/or police committed over 2600 armed incursions into the North. Subsequently, documents have suggested that, at a minimum, there were a number of attacks by South Korean forces into the North, and that many, if not all, of the attacks on the South had been reprisals. Note how Wikipedia conveys one altercation:

“Serious border clashes between South and North occurred in August 1949, when thousands of North Korean troops attacked South Korean troops occupying territory north of the 38th parallel.”

South Korean already had troops north of the border, but in this rendition it was the North that attacked.

Captain James H. Hausman wrote in a briefing note for General Roberts in August of 1949,

“My counterpart and I are firmly convinced that all attacks on South Korea have been reprisals, and almost all incidents have been agitated by the South Korean security forces.”

Col. Min Ki Sik, Assistant Commandant of the Korean School of Arms observed in 1949,

“One usually hears that the Army never attacks North Korea and is always getting attacked. This is not true. Mostly our Army is doing the attacking first and we attack harder.”

Syngman Rhee’s public pronouncements throughout 1949 and early 1950 consistently spoke of his desire to order his forces to attack the North. On September 30, 1949 he stated,

“I feel strongly that now is the most psychological moment when we should take an aggressive measure.”

The Washington Post quotes him saying on November 1 1949,

“My government will not much longer tolerate a divided Korea,” and “If we have to settle this thing by war, we will do all the fighting needed.”

According to the North Korean government, the North Korean attack on South Korea on June 25, 1950 was a response to a two-day long bombing by the South Koreans and their surprise attacks on the city of Haeju and other places. Early in the morning of June 25th , before the dawn counterattack in the North Korean account, the South Korean Office of Public Information announced that the Southern forces had captured Haeju. The South Korean government later denied capturing the town and blamed the report on an exaggerating officer. Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union proposed that North Korea be invited to the UN Security Council to present its side of the story, but the propoal was voted down.

Whatever the cause, North Korean soldiers did cross the border on June 25th, and by June 28th they were in Seoul (which is only 35 miles away). The South Korean Army effectively fell apart; between June 25 and June 28 South Korean forces diminished from 95,000 men to 22,000, almost all of the loss due to desertions. The South would have lost the war in a week had the US not intervened.

On the day Seoul fell President Rhee ordered the killing of anyone deemed to be a political opponent anywhere in South Korea. Killings occurred everywhere that was still held by South Korean forces. Numerous massacres took place, many of them not directed against so-called but rather common citizens. For example On February 7, 1951, 705 unarmed citizens in the villages of Sancheong and Hamyang, were lined up and killed by the South Korean Army. Two days later 719 civilians from the village of Geochang were shot.

U.S. Colonel Donald Nichols, a personal friend of Rhee, reported witnessing in Suwon, south of Seoul, the massacre of 1,800 political prisoners in late June 1950. He described the work of two bulldozers, one gouging a series of trenches, the other filling in dirt over the shot bodies after they had been dumped into the fresh graves. Gregory Henderson, who served as a U.S. diplomat in Korea during the late 1940s and early 1950s, estimated that “probably over 100,000 South Korean civilians were killed without any trial whatsoever” by Rhee’s forces during the war.

The outbreak of fighting created a mass of refugees trying to flee to safety. There were so many that they blocked military movements along the roads; orders were given by U.S. military commanders to shoot the refugees. On July 26 1950 the US 8th Army, the highest level of command in Korea, issued orders to stop all Korean civilians. ‘No, repeat, no refugees will be permitted to cross battle lines at any time. Movement of all Koreans in group will cease immediately.’ After this refugees were regularly gunned down as they tried to flee the war.

On the very day that the US 8th Army delivered its stop refugee order in July 1950, up to 400 South Korean civilians gathered by bridge at No Gun Ri were killed by US forces from the 7th Cavalry Regiment. Some were shot above the bridge, on the railroad tracks. Others were strafed by US planes. More were killed under the arches in an ordeal that local survivors say lasted for three days.

“There was a lieutenant screaming like a madman, fire on everything, kill ’em all,” recalls 7th Cavalry veteran Joe Jackman. “I didn’t know if they were soldiers or what. Kids, there was kids out there, it didn’t matter what it was, eight to 80, blind, crippled or crazy, they shot ’em all.”

The highest law officer in the land, President Truman’s second Attorney General, J. Howard McGrath, referred to the Koreans as “rodents,” and thus had no regrets about the ongoing slaughter.

Meanwhile the US easily destroyed North Korea’s meager air force and air defences, and began an unimpeded bombing campaign of the north on June 29, 1950 that lasted for three years. Over that period, U.S. forces flew one million-forty thousand sorties and dropped 386,037 tons of bombs and 32,357 tons of napalm. If one counts all types of airborne ordnance, including rockets and machine-gun ammunition, the total tonnage comes to 698,000 tons. The U.S. destroyed every city, every village, every dam, every railroad, and every highway in the North Korea. An estimated 2.5 million North Koreans died in the bombing, most of them civilians, many of them incinerated by napalm. Flier Federic Champlin observed that,

“One thing about napalm is that when you’ve hit a village and have seen it go up in flames, you know that you’ve accomplished something. Nothing makes a pilot feel worse than to work over an area and not see that he’s accomplished anything.”

On June 25, 1951, General O’Donnell, commander of the Far Eastern Air Force Bomber Command, testified in answer to a question from Senator John C. Stennis (“North Korea has been virtually destroyed, hasn’t it?”):

“Oh, yes; … I would say that the entire, almost the entire Korean Peninsula is just a terrible mess. Everything is destroyed. There is nothing standing worthy of the name. Just before the Chinese came in we were grounded; there were no more targets in Korea.”

In 1952 General Curtis LeMay stated,

“We have bombed every city twice, now we are going back to pulverize them into stones.”

In August 1951, war correspondent Tibor Meráy stated that he had witnessed “a complete devastation between the Yalu River and the capital.” He said that there were “no more cities in North Korea.” He added,

“My impression was that I am traveling on the moon because there was only devastation—every city was only a collection of chimneys.”

The war’s highest-ranking U.S. POW, U.S. Major General William F. Dean, reported that the majority of North Korean cities and villages he saw were either rubble or snow-covered wasteland. As a final florish to this nationwide destruction, General MacArthur in December of 1950 requested 34 atomic bombs to use to create a nuclear wasteland along the Chinese border. Although this request was turned down, President Truman and others repeatedly contemplated how to best use atomic bombs in the war.

After Truman fired General MacArthur in May 1951, the former ‘supreme commander’ testified to Congress.

“The war in Korea has already almost destroyed that nation of 20 million people. I have never seen such devastation…..After I looked at that wreckage and those thouands of women and children…..I vomited.”

Three years after the beginning of the war, a cease-fire was finally signed. Everything was back to where it had been at the beginning, with almost the same borders as before the war and the same unfulfilled dream of reunification. No one had won. Everyone had lost. The war is calculated to have cost the lives of up to 5 million people, by far the majority of them civilians.

A few lessons could have been learned from the Korean War. One is, as famed journalist I.F. Stone observed,

“Every government is run by liars and nothing they say should be believed.”

Another would be the recognition, as voiced by war veteran Mike Hastie, that

“The United States is a non-stop killing machine.”

Because we live within the lies told by our government and therefore fail to learn, after Korea the U.S. went on to devastate Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya…….causing human suffering beyond comprehension and massive destruction of human and natural systems.

Let us therefore say, as a thought experiment, that you are the only mature adult in the room, and it is therefore your responsibility to subdue the pathological personalities that inevitably pop up as leaders of the U.S. government and U.S. military—subdue them for the sake their long-suffering victims and for the sake of the health and viability of the Earth’s ecosystems and biosphere as a whole. What are you going to do, it’s up to you?

Here is one possible way forward. After the Soviet Union fell apart, Gorbachev said “It was an evil system, it had to be dismantled.” Surely this profoundly criminal U.S. system has to be dismantled as well.

“The greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government. For the sake of the hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent.” — Martin Luther King

Dana Visalli is an ecologist and organic farmer living in Twisp, Washington.