“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…” These lines are now inseparable from the Statue of Liberty. They are part and parcel of the postwar American identity. They speak to our nature as a so-called, “nation of immigrants,” and are wielded as a weapon to silence anyone concerned about endless, unchecked immigration into submission. As far as our modern national mythos goes, the aforementioned words might as well have been uttered by our Founding Fathers, and going against their spirit is almost tantamount to treason against “our democracy.”

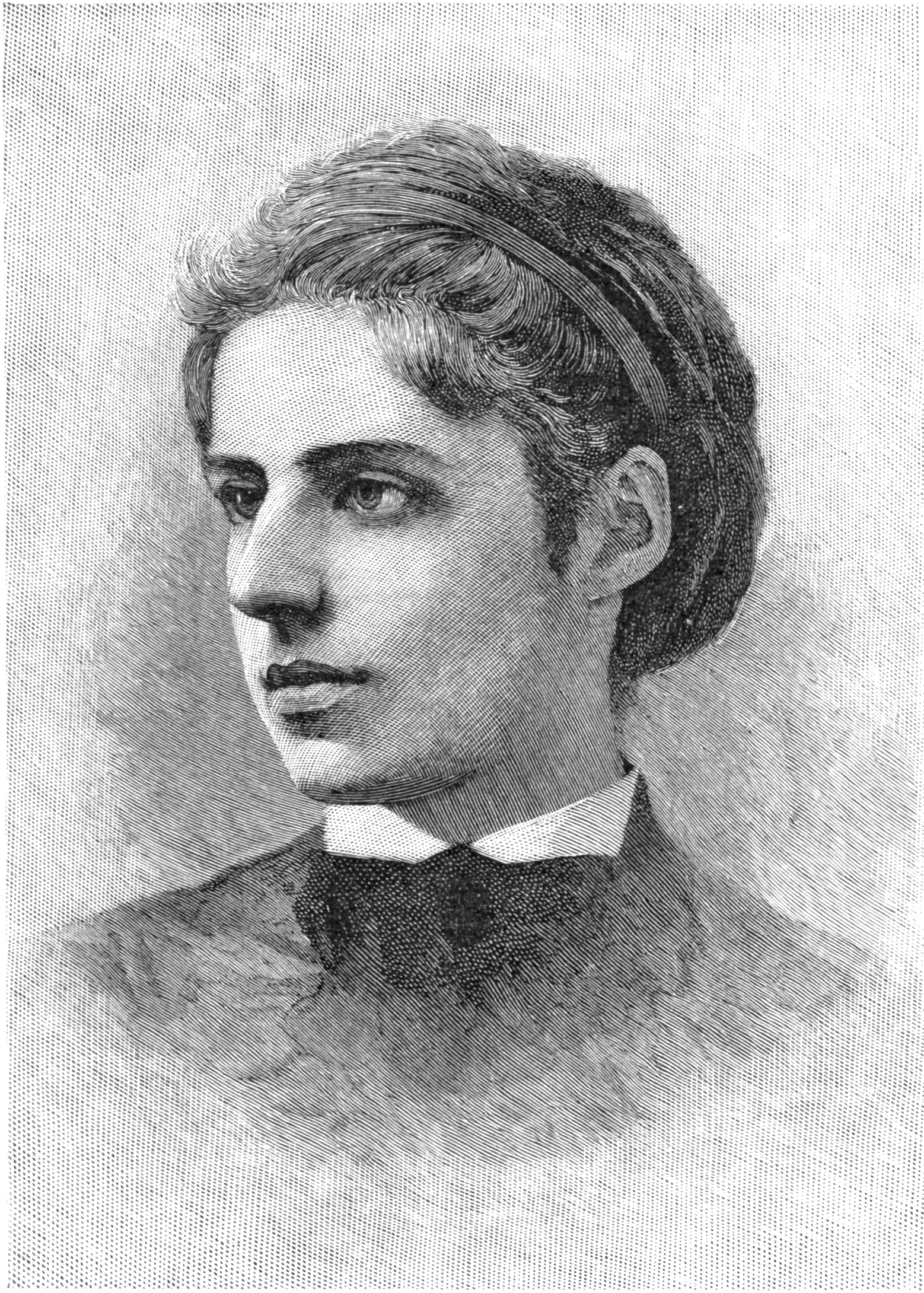

In reality, the lines are from a sonnet called The New Colossus, written in 1883 by Emma Lazarus, a Jewish writer and social activist. Unbeknownst to most Americans, the poem had no official association with the statue until 1903, when Georgina Schuyler, one of Emma’s friends, led a civic campaign to have the sonnet cast onto a bronze plaque and mounted inside the lower level of the pedestal, 17 years after the statue was first dedicated. The poem was rarely mentioned in the mainstream press until several decades later.

The New Colossus appears to have gained traction once Slovenian author and socialist immigrant Louis Adamic began quoting it in his writings during the late 1930’s to combat the Johnson-Reed act of 1924, which set restrictive immigration quotas in order to maintain America’s ethnic homogeneity. Adamic was an avid Marxist who advocated for ethnic diversity in the US, and coincidentally, his publisher, Maxim Lieber, was named by the Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers as an accomplice in 1949. Lieber fled to Mexico in 1951 and eventually back to Poland. Louis Adamic committed suicide in 1951 under suspicious circumstances.

Over time, the poem’s association with the statue has grown to the point of absurdity. Again, today, questioning, altering or rejecting the poem and its meaning is a kind of political blasphemy. For example, back in 2019, the press berated the Trump Administration for supposedly “rewriting” Emma Lazarus’s words when Ken Cuccinelli, Trump’s head of Citizenship and Immigration Services, tried to reorient the poem’s meaning.

CBS wrote: Trump’s top immigration official reworks the words on the Statue of Liberty. PBS wrote: Trump official says Statue of Liberty poem is about Europeans. The New York Times wrote: What the Trump Administration Gets Wrong About the Statue of Liberty. Vox wrote: Trump official suggests famous Statue of Liberty sonnet is too nice to immigrants. The Jewish Forward wrote: Ken Cuccinelli Isn’t The First Trump Official To Go After Emma Lazarus.

All these accusations of “rewriting” Emma’s poem were ironic, since essentially it was Emma’s poem that was used to rewrite America’s identity and its stance on immigration. Concerning the period of the Johnson Reed Act of 1924, leading up to the Hart Celler act of 1965, Hugh Davis Graham wrote in his book Collision Course:

Most important for the content of immigration reform, the driving force at the core of the movement, reaching back to the 1920s, were Jewish organizations long active in opposing racial and ethnic quotas. These included the American Jewish Congress, the American Jewish Committee, the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, and the American Federation of Jews from Eastern Europe.[1]

Curiously, in 1883, when a fundraising committee asked Emma Lazarus to donate an original work to an auction intended to help pay for the pedestal’s construction, Emma declined saying that she would not write about a statue. She only changed her mind after Constance Cary Harrison convinced her that it would be of great significance to immigrants sailing into the harbor.[2]

As Harrison later recalled, her ploy to win over the young writer involved highlighting the plight of immigrants from a very specific ethnic background:

Think of that Goddess standing on her pedestal down yonder in the bay, and holding her torch out to those Russian refugees of yours you are so fond of visiting at Ward’s Island.[3]

These “Russians” were in fact Emma’s fellow Jews fleeing pogroms in Russia after Czar Alexander II’s assassination in which Jewish radicals had been implicated. In any event, It seems that just as the Anglo-Saxon founders of America had a preference for immigrants of a certain ethnic background, Emma had her own preferences too. She didn’t write poems about Irish or Italian gentiles who were immigrating in large numbers at the time. Nor did she write about emancipated slaves in the South or Chinese railroad workers out west. To the extent that she wrote about any people, it was almost exclusively Jews.

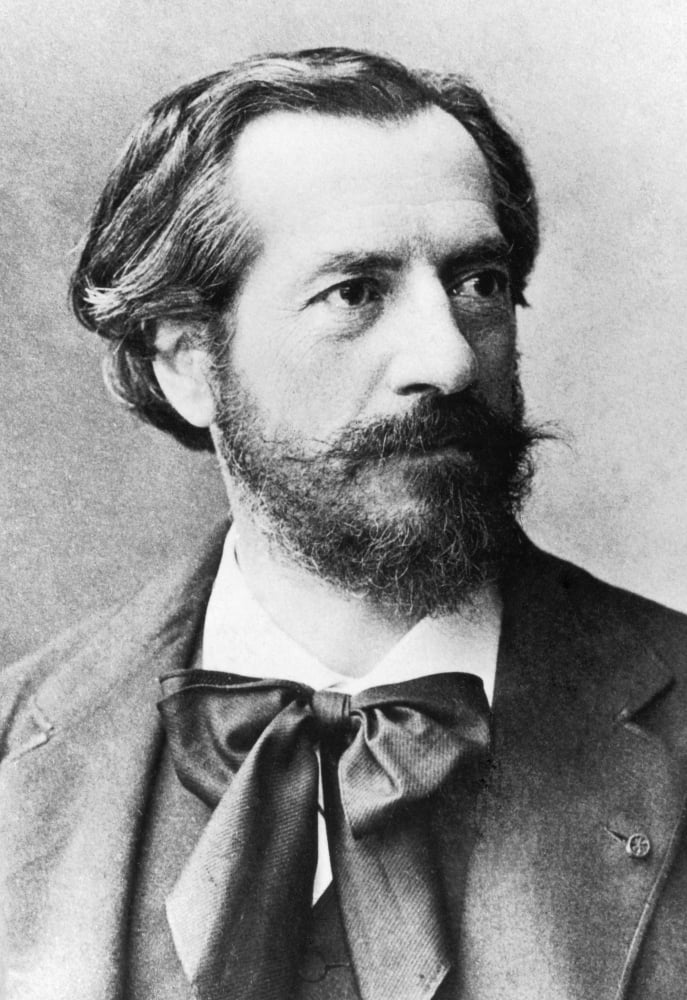

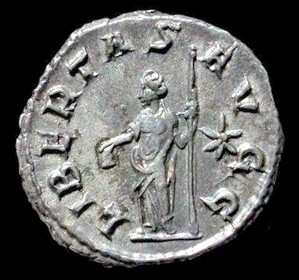

The greatest tragedy in the history of Lady Liberty is that more people know who Emma Lazarus was than the Frenchman who designed it; Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. The statue was a gift from France to celebrate the nations’ friendship and alliance. It was modeled after Libertas, a roman goddess who was often associated with freed slaves in antiquity. But the monument really had nothing to do with the emancipation of African slaves in the US, and great care was taken in the design to avoid such associations.[4]

The meaning behind Lady Liberty is no where near as convoluted as popular media makes it out to be. The Roman goddess, Libertas, has been used in various forms by many European peoples for centuries. There’s a version of her on top of the Capitol building that was put in there in 1863. France used her on their seal for the second French Republic in 1848. There’s also the Dutch Maiden, the United Kingdom’s Britannia, and the Italia Turrita.

In the American setting, the figure of Libertas was used as a symbolic reference to the freedom the British colonists had gained from their English monarch, King George. The date written on the statue’s Tabula Ansata is July 4th, 1776, the date of independence from England. This is also the date mentioned numerously in French fundraising pamphlets which, as far as I am aware, never spoke of emancipated slaves or immigrants.

It is true that Édouard Laboulaye, one of the key impetuses behind the statue, was a passionate abolitionist who advocated on behalf of emancipated slaves, but his motivation for building the monument was to further solidify the historic Franco-American alliance.

In 1875, he launched a subscription campaign for France’s half of the funding saying:

This is about erecting in memory, on the glorious anniversary of the United States, an exceptional monument. In the middle of New York’s harbor, on an islet that belongs to the Union, and opposite Long Island, where the first blood for independence was spilt, here will stand a colossal statue, framed on the horizon by the great American cities of New York, Jersey City and Brooklyn. On the threshold of this vast continent full of a new life, where all the ships of the world arrive, it will emerge from the heart of the waves, it will represent: Liberty enlightening the world. At night, a luminous halo emanating from her forehead, will radiate in the distance on the immense sea.[5]

The idea of Liberty enlightening the world was that others could achieve what America had by following in its example as a republic. Laboulaye and others didn’t see Lady Liberty as a call for endless, unqualified immigration, and it was not a statement that anyone could be American regardless of national origin.

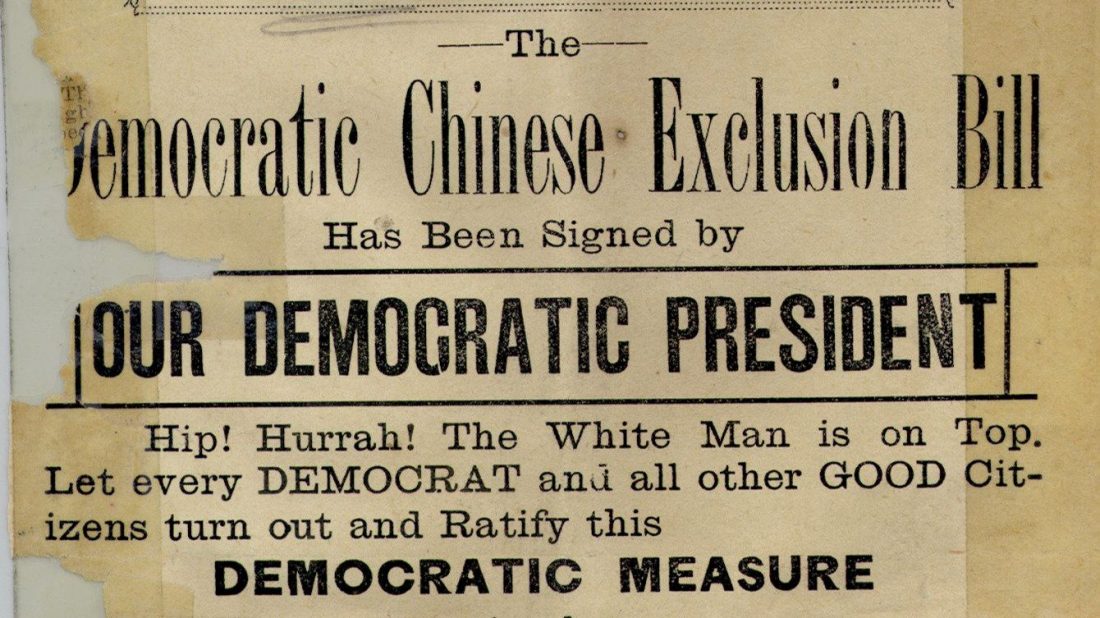

To drive home the absurdity of claims to the contrary, four years prior to the the statue’s dedication, America had passed the Chinese Exclusion act thereby barring an entire racial bloc from immigrating.

Shortly before being assassinated in 1865, Lincoln, the great emancipator, had told General Benjamin Butler:

“I can hardly believe that the South and North can live in peace, unless we can get rid of the negroes…I believe that it would be better to export them all to some fertile country…”[6]

In the 1880s, race riots were common. Most Americans continued to share Lincoln’s sentiments and saw ex-slaves as an unresolved problem with many politicians and private citizens continuing to argue for them to be repatriated to Africa.

The Cleveland Gazette, an African American newspaper wrote the following regarding the Statue of Liberty’s dedication:

“Liberty enlightening the world,” indeed! The expression makes us sick. This government is a howling farce. It can not or rather does not protect its citizens within its own borders.[7]

Such language is often highlighted to assert that America was failing to live up to its supposed ideals, but the reality is that America’s first naturalization act in 1790, in no uncertain terms dictated that citizenship was reserved for “free white person[s]…of good character.” When Thomas Jefferson said in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,” he was speaking in a political sense to King George, a monarch, and not a literal sense to mankind as a whole.

Other contemporary state documents remove the ambiguity for the modern reader, such as that of Virginia’s Declaration of Rights in 1776:

“…all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights…”

None of the sentiments outlined in any of our founding documents sought to convey that all men, regardless of racial background or national origin, were equal and interchangeable in a literal sense commensurate with modern notions of “diversity, equity and inclusion.”

Thomas Jefferson, despite being a slave owner himself, did support emancipation, but he qualified this in his Notes on the State of Virginia:

“Among the Romans emancipation required but one effort. The slave, when made free, might mix with, without staining the blood of his master. But with us a second is necessary, unknown to history. When freed, he is to be removed beyond the reach of mixture.”[8]

Of note here is that the definition of “Civil Rights” has changed substantially over time. In 1866 when the first Civil Rights Act was passed, John Wilson, a member of the Radical Republicans, described what the legislation was intended to encompass when he presented it before congress:

It provides for the equality of citizens of the United States in the enjoyment of “civil rights and immunities.” What do these terms mean? Do they mean that in all things civil, social, political, all citizens, without distinction of race or color, shall be equal? By no means can they be so construed. Do they mean that all citizens shall vote in the several States? No; for suffrage is a political right which has been left under the control of the several States, subject to the action of Congress only when it becomes necessary to enforce the guarantee of a republican form of government (protection against a monarchy). Nor do they mean that all citizens shall sit on the juries, or that their children shall attend the same schools.[9]

Let’s return to Emma Lazarus’s poem, The New Colossus. It’s quite short so let’s read it:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

In her biography of Emma Lazarus, a fellow Jewess, Esther Schor, considers the meaning that can be gleaned from these lines:

Perhaps, too, these words issue a mild command that a new-world statue must embody a new ideal. But before her vision takes shape, she pauses to smash an idol of the Old World: Helios, the sun god, a figure of imperial conquest, “astride from land to land.” Given that Bartholdi’s statue was intended to ennoble enlightenment, her reference to Helios’s lust for domination is indecorous, to say the least.

In “Progress and Poverty,” she had already impugned the lit lamp of Science for being complicit with exploitation. Now, renaming Liberty Enlightening the World “Mother of Exiles,” she relieves this giant female form of a heavy inheritance of tyranny. At the same time, she places a new burden upon her, asking that she nurture and protect conquest’s victims.

The “imprisoned lightning” of her flame, an emblem of captive, not liberating light, insists that true enlightenment must wait on freedom. Until then, all light glows against a scrim of darkness, the same darkness in which the ignorant slaves of “Progress and Poverty” toiled.[10]

Esther Schor seemingly acknowledges that Emma profaned Bartholdi’s original intent and yet embraces Emma’s view as the more legitimate one anyway. She continues:

Defying the “storied pomp” of antiquity, precedent, and ceremony, the statue speaks not in the new language of reason and light but in the divine language of lovingkindness. To worldly power, she sounds a dire tattoo: “Keep, ancient lands”; “Give me your tired.” To the abject, she offers the silent salute of her lamp. What it illuminates are shapes of human suffering, the “huddled masses,” the wretched refusés on the Old World’s “teeming shore.” Emma Lazarus had finally arrived, from a glimpse of the “undistinguished multitudes” in her elegy to Garfield, at a more radical, embracing vision of American society, and she had been led there by her Jewish commitment to repair a broken world. She knew well that for these homeless throngs, becoming individuals—becoming free Americans—would not be easy. But it was their destiny. In time, the Mother of Exiles assures them, that is what they would grow to become.[11]

Putting aside that the base inspiration of the Statue of Liberty was the Roman goddess Libertas and that Helios wasn’t really associated with conquest, the Colossus of Rhodes, was literally built using the siege equipment left by the Macedonians after their failed attempt to take the city, and, like its modern female counterpart, was a monument to continued independence.

Now, one could make the case that Esther Schor, is anachronistically imbuing Emma with 21st-century interpretations of tikkun olam, but it seems fairly obvious that Emma was driven, at least in part, by a kind of Jewish ethnocentrism, and a resentment of Western society and her place in it as a Jew.

Again, Emma didn’t write about the plight of blacks in the South, nor did she spend her time protesting the Chinese Exclusion act. Before the term Zionism had even been coined, Emma was traveling around Europe advocating for a Jewish ethnostate in Palestine. Her line “keep ancient lands your storied pomp” in defiance of European antiquity, precedent and ceremony is ironic since a great deal of her other literary works focused on exalting Jewish antiquity, precedent and ceremony. In fact, Emma is considered by many to be the archetypical American Zionist. Oddly enough, Esther Schor admits as much in the preface of her book:

These days, Lazarus’s dictum that “Until we are all free, we are none of us free” is widely taken to be a universalist credo; similar statements are attributed to Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. In fact, Lazarus addressed this comment expressly to the privileged, emancipated Jews of the West, taking them to task for “not [being] ‘tribal’ enough”—that is, for failing to recognize the persecuted Jews of Russia as their brothers and sisters.[12]

But in the same preface, she asserts that Emma’s behavior was more or less a proto-universalist movement gearing up to include all of humanity.

For Emma Lazarus, being Jewish meant acknowledging one’s bonds to people distant in both place and time. Being a free Jew, in a world where Jews were being persecuted and expelled by the thousands, sometimes even killed and raped, was to incur the obligation to bring freedom to others. It was Lazarus’s genius to understand that the obligations of freedom pertained not only to Jewish Americans, but to all Americans.[13]

Needless to say, I find this highly disingenuous and self-serving. If we look deeper into Emma’s family history, such notions of her being some proto-archetypal form of modern “diversity, equity, and inclusion” becomes somewhat absurd. Her family was among the original twenty-three Portuguese Jews who moved to New York in 1654 when it was still called New Amsterdam and was controlled by the Dutch.[14]

They were fleeing the return of the Inquisition in their settlement of Recife, Brazil. So yes, her family was fleeing persecution, but Recife, Brazil was one of the most important colonies in the New World in terms of establishing the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the infamous Middle Passage.

According to Jewish author Herbert Bloom:

The Christian inhabitants of Brazil were envious because the Jews owned some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco and were among the leading slave-holders and slave traders in the colony.[15]

In reference to slave colonies in Brazil and the West Indies, Jewish historian Marc Lee Raphael wrote that:

Jews also took an active part in the Dutch colonial slave trade; indeed, the bylaws of the Recife and Mauricia congregations (1648) included an imposta (Jewish tax) of five soldos for each Negro slave a Brazilian Jew purchased from the West Indies Company. Slave auctions were postponed if they fell on a Jewish holiday. In Curacao in the seventeenth century, as well as in the British colonies of Barbados and Jamaica in the eighteenth century, Jewish merchants played a major role in the slave trade. In fact, in all the American colonies, whether French, British, or Dutch, Jewish merchants frequently dominated.[16]

In 1522, according to Jewish professor, Arnold Wiznitzer, Jews exiled from Portugal established sugar plantations and mills on the island of São Tomé off the West African coast, “employing as many as 3,000 Negro slaves“, thereby allowing the Portuguese to “dominate the world sugar trade.” In reference to the early colonization of Brazil he says that:

It is a historical fact, supported by documentary evidence that a consortium of Jews, headed by Fernnão de Norohna, had obtained in 1502 a three-year lease from the Portuguese Crown for the exploration and settlement of the newly discovered Brazil. The lease, constituting in reality a monopoly, was extended for an additional ten years in 1505.[17]

The 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia also states that Jews “monopolized” the sugar industry in the 17th century.[18] In reference to the late 17th century and early 18th century, Seymour Liebman said in his book New World Jewry that:

… The Jews were the largest ship chandlers in the entire Caribbean region, where the shipping business was mainly a Jewish enterprise. The Jews were the principal purveyors to the government, although there never were more than two thousand Jews in Curacao. It is conservatively estimated that the Jews owned about two hundred vessels during the first sixty years of their settlement in Curaçao.[19]

Regarding Jewish slave ownership in the United States during the 1800s, many Jewish historians and advocates point out that most Jewish slave owners only possessed a few domestic slaves whom they employed as house servants. This is likely true but doesn’t warrant any special consideration, in my opinion.

As the Economic History Association points out, this was essentially the standard for slavery in America at the time:

Most Southerners owned no slaves and most slaves lived in small groups rather than on large plantations. Less than one-quarter of white Southerners held slaves, with half of these holding fewer than five and fewer than 1 percent owning more than one hundred. In 1860, the average number of slaves residing together was about ten.

Jewish historian Jacob Rader Marcus asserted in his book United States Jewry 1776-1985 that in 1820, 40% of Jewish households owned slaves.[20] The population of Jews at that time was considerably lower than it is today both in number and in proportion, however, by 1860 Jews in America numbered between 150,000 and 200,000, out of a total population of 27,000,000. Or roughly 0.7% of the population. The total amount of slave owners in 1860 was a little less than 400,000, per the 1860 census. If we assume that the percentage of Jewish slave ownership in 1860 was the same as it was in 1820, then Jews would’ve accounted for between 10-15% of total slave owners at the height of American slavery. 0.7% of the population accounting for up to 15% of slave ownership is a remarkable overrepresentation.

I will offer the caveat here, however, that there was an increasing influx of poor Jewish immigrants between 1820 and 1860, so it may be doubtful that all of them were able to afford slaves. But as a colleague of Jacob Rader Marcus once said:

…Jews who were more firmly established in a business or professional career, as well as in their family relation-ships, had every reason to become slave-owners…[21]

In addition to this, I would highlight that in reference to the early period of the 1700s in America, the Jewish encyclopedia also states that:

The Jews of Georgia found the production of indigo, rice, corn, tobacco, and cotton more profitable. In fact, many of the cotton plantations in the South were wholly in the hands of the Jews, and as a consequence, slavery found its advocates among them.[22]

To be clear, Jews were not the sole instigators or beneficiaries of the slave trade, but they were undoubtedly overrepresented in all facets of it whether directly in the form of ownership, or participation in ancillary industries. With this in mind, it is exceedingly unlikely that Emma Lazarus’s Brazilian ancestors didn’t own slaves, and while her immediate family in 19th century New York did not directly engage in slavery, her father, Moses Lazarus, was in the sugar refining and distillery industry. The raw sugar used in his factories came from slave plantations in the South owned by his business partner whom Esther Schor briefly comments on in her book:

Moses’s unsavory business partner, Bradish Johnson, a slaveholder from Louisiana, had been cited for the abuse of slaves on his plantation. The owner of a combination dairy/distillery in Manhattan, Johnson was also cited in an 1853 New-York Daily Times exposé for selling tainted milk: apparently, his cows had been lapping up alcoholic swill sluiced from the distillery. With such a disreputable partner, it was no wonder Moses gave out that he had retired from Johnston and Lazarus at the close of the Civil War.[23]

What Esther seemingly tries to brush aside here is that the distillery in question was called The Johnson & Lazarus distillery. Emma’s father was Johnson’s equal in their shared business firm and was every bit as responsible for this scandal as was Johnson. Moreover, Moses Lazarus didn’t just retire from The Johnson & Lazarus firm in 1865; he retired outright. Esther seemingly attempts to portray Moses Lazarus’s retirement as some moral epiphany 12 years after the scandal.

To put the scandal into perspective, during the 1850s between 8,000 to 9,000 children were dying, every year in New York City, due to “impure” or “adulterated milk.”[24] For reference, New York City had a population of about 515,000. So something on the order of 1 to 1.5% of the local population was dying from things like dysentery, cholera infantum, and marasmus.

Swill milk was the milk produced by cows fed a residual byproduct of alcohol production from nearby distilleries. After the extraction of alcohol from the macerated grain, the residual mash still contained nutrients, and it was an economic advantage to keep cows stabled nearby and feed it to them. The milk had a blue tint and was extremely thin, so it was whitened with plaster of Paris, thickened with starch and eggs, and hued with molasses.

Now, to be fair to Bradish Johnson and Moses Lazarus, swill milk was produced and sold all over New York at the time. However, as John Mullaly pointed out in his work The Milk Trade in New York and Vicinity, published in 1853:

The most extensive distillery in the city is that owned by a Mr. Johnson, at the foot of Sixteenth Street, on the North River. It produces more swill than any other in New York, and it is said, even more than any other in the United States.[25]

The truth is that Emma Lazarus’s family profited off human exploitation. It’s what paid for Emma’s fancy tutors, summer homes, and travel to Europe to advocate for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Emma was not an independent woman. She did not disown her family or its businesses. She lived with her family until she died unmarried in 1887 from Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

In fact, had it not been for Emma’s father, she might never have achieved any sort of notoriety. In 1866 Moses Lazarus paid to have Emma’s first works published:

In his accomplished seventeen-year-old daughter, Moses Lazarus had much to crow about, but Emma Lazarus’s debut volume, which he had printed “for private circulation,” took paternal pride to Olympian heights. Poems and Translations, Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Sixteen ran to more than two hundred pages, comprising nearly thirty “Original Pieces,” two hulking romances each in excess of a thousand lines, and translations of forty-five short lyrics by Heine, Schiller, Dumas, and Hugo. Dedicated, unsurprisingly, “To My Father,” it appeared in November 1866.[26]

It was only after this that she was taken on as a protégé by famous writer, Ralph Waldo Emerson. Interestingly, her relationship with Emmerson appears to have deteriorated over time due to what Esther Schor called “the sense of entitlement her elite, Sephardic parents had instilled in her.”[27]

What motivated Emma in the 1880’s was probably not transcendentalism so much as it was an emerging sense of ethnic solidarity with her Ashkenazic counterparts in Russia. In an 1882 letter to a friend, she wrote:

Indeed, I would love to see you in your own home and visit dear old Concord again… But I may have imperative duties recalling me to New York in connection with work for the Russian Jews… The Jewish Question which I plunged into so wrecklessly and impulsively last Spring has gradually absorbed more and more of my mind and heart—It opens up such enormous vistas in the past and future, and is so palpitatingly alive at the moment…that it has about driven out of my thought all other subjects….[28]

Author Bette Roth Young explains Emma’s view of Benjamin Disraeli, England’s only Jewish prime minister and founder of the modern conservative party. Using many of Emma’s own words she writes:

Emma continued her adulation telling the reader that no Englishman could ever forget that Disraeli was a Jew; Therefore “he himself would be the first to proclaim it, instead of apologizing for it.” Rather than “knock servilely at the doors of English aristocracy,” he “conquered them with their own weapons, he met arrogance with arrogance, the pride of descent based upon a few centuries of distinction, with the pride of descent supported by hundreds of centuries of intellectual supremacy and even of divine anointment.”[29]

In a New York Times article attributed to Emma Lazarus, after a visit to Ward’s Island, Emma wrote:

Never before were the prayer of gratitude and the impulse of joy more genuine, more appropriate, and more solemn than on this day of March, 1882, when after a new exodus, and a new persecution by the seed of Haman, these stalwart young representatives of the oldest civilization in existence met to sing the songs of Zion in a strange land.[30]

Note that Emma refers to Russian gentiles as the “Seed of Haman,” and by doing so she is imbuing Russians with a deeply rooted, millennia-old animosity that Jews felt toward their biblical enemies. In fact, much of Emma’s work and activism around the 1880’s was squarely centered on arousing sentiments of Jewish Nationalism in the Jewish diaspora. Take for example her poem, The Banner of the Jew. In it, she calls upon the nation of Israel to rise up and refers to the rebellion in 164 BC against the Greeks as a “glorious Maccabean rage.”

The Maccabean revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BC and was fought by Jewish nationalists against the Greeks for their Hellenistic influence on Jewish life in Judea. Hanukkah, the most famous Jewish holiday, is downstream of this revolt.

Chabad.org describes the revolt as follows:

In the second century BCE, the Holy Land was ruled by the Seleucids, who tried to force the people of Israel to accept Greek culture and beliefs instead of mitzvah observance and belief in G‐d. Against all odds, a small band of faithful but poorly armed Jews, led by Judah the Maccabee, defeated one of the mightiest armies on earth, drove the Greeks from the land, reclaimed the Holy Temple in Jerusalem and rededicated it to the service of G‐d.

Honestly, Hanukkah sounds like something the authorities today would normally consider “hate speech,” since it celebrates armed violence against culturally enriching immigrants and seeks to drive them out. It’s easy to imagine how various Jewish interest groups and the European Union might react if native European poets started writing today about a “glorious Hyperborean rage.”

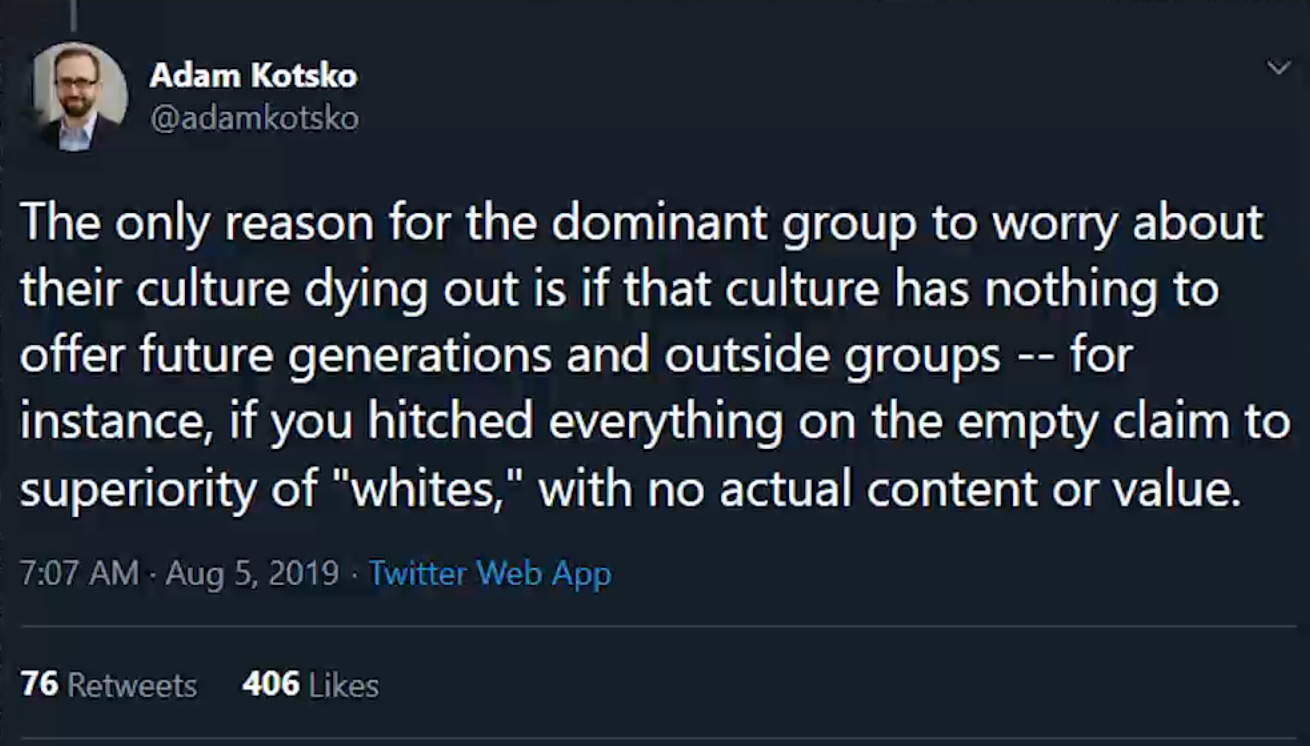

The Maccabean revolt also targeted Hellenized Jews who embraced Greek culture over Jewish laws and customs. (Mattathias ben Johanan famously killed a fellow Jew who had followed the order of a Greek official to offer sacrifice to the Greek gods.) That is to say, these Hellenized Jews thought that the incoming immigrant culture had something better to offer future generations. At least, that seems to be how Adam Kotsko views such situations, if we consider his frame describing the concerns white Americans have about endless non-white immigration and our dying culture. (See the screencap below) If Adam were consistent, he might condemn the Maccabean revolt as having “hitched everything on the empty claim to the superiority of [Jews] with no actual content or value.”

With this Jewish revolt against the Greeks in mind, it’s interesting that Emma Lazarus made it a point in The New Colossus to contrast the masculine Greek statue of Rhodes with her proto-feminist interpretation of Libertas. In her mind, Lady Liberty is a welcoming, “mother of exiles,” whereas the Colossus of Rhodes is an imposing male straddling his legs across the bay in a show of dominance.

Perhaps just as the Greeks defiled her peoples’ temple in the Levant, she was now defiling a temple of sorts belonging to the American “Seeds of Haman.” Either way, Emma Lazarus took it upon herself to hijack an otherwise noble gift from one nation to another, and make it about Jewish grievances.

In her weekly column, “An Epistle to the Hebrews” she describes the dilemma facing her Ashkenazic counterparts:

Either these Jews would submit to the inevitable and relinquish that fundamental piety and austerity which even in the degradation of their Russian Ghettos has preserved their moral tone, and given them a certain amount of dignity, or else, true to the traditions of their race, they would bulwark themselves within a citadel of isolation and defiance, and accept martyrdom and death rather than forego that which they consider their divine mission….For the mass of semi-Orientals, Kabalists and Chassidim, who constitute the vast majority of East European Israelites, some more practical measure of reform must be devised than their transportation to a state of society utterly at variance with their time-honored customs and most sacred beliefs.[31]

Naturally Emma’s language poses the question: How does one become assimilated to a state of society utterly at variance with one’s self? But, does Emma really sound like a woman advocating assimilation? What she wrote here is that Jews are a “race,” that is… a biological collective, that needs a nation of its own. But, more curious still, Emma argued another point in her weekly column:

There is not the slightest necessity for an American Jew, the free citizen of a republic, to rest his hopes upon the foundation of any other nationality soever, or to decide whether he individually would or would not be in favor of residing in Palestine. All that would be claimed from him would be a patriotic and unselfish interest in the sufferings of his oppressed brethren of less fortunate countries, sufficient to make him promote by every means in his power the establishment of a secure asylum.[32]

So, in other words, Jews are entitled to a homeland, if they so desire, or they can reside among the gentiles, if they so desire, but, according to Emma, Jews must always put the welfare of their fellow Jews, first and foremost.

Today Chuck Schumer can proudly stand before AIPAC, as a senator of the United States, and proclaim that he is, first and foremost, the guardian of Israel and its people, yet when someone like Jared Taylor proclaims, as little more than a private citizen, that he would like the right to pursue his destiny alongside his ethnic brethren without outside interference, he is immediately branded a hateful “supremacist.”

Israel’s prime minister, Netanyahu, said regarding African migrants in 2012 that:

If we don’t stop their entry, the problem that currently stands at 60,000 could grow to 600,000, and that threatens our existence as a Jewish and democratic state.

In 2018, he said that without a stronger border fence along the Sinai border:

…we would be faced with … severe attacks by Sinai terrorists, and something much worse, a flood of illegal migrants from Africa…

In her efforts to arouse sentiments of Jewish Nationalism, Emma Lazarus sometimes quoted the Talmud saying: “let the fruit pray for the welfare of the leaf.”[33] In a 2001 article entitled The Jewish Stake in America’s Changing Demography, Steven Steinlight expressed an indirect concern over the welfare of the demographic leaf of white American gentiles:

Is the emerging new multicultural American nation good for the Jews? Will a country in which enormous demographic and cultural change, fueled by unceasing large-scale non-European immigration, remain one in which Jewish life will continue to flourish as nowhere else in the history of the Diaspora? In an America in which people of color form the plurality, as has already happened in California, most with little or no historical experience with or knowledge of Jews, will Jewish sensitivities continue to enjoy extraordinarily high levels of deference and will Jewish interests continue to receive special protection?…

…For perhaps another generation, an optimistic forecast, the Jewish community is thus in a position where it will be able to divide and conquer and enter into selective coalitions that support our agendas. But the day will surely come when an effective Asian-American alliance will actually bring Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, Koreans, Vietnamese, and the rest closer together. And the enormously complex and as yet significantly divided Latinos will also eventually achieve a more effective political federation.

While Jews do not monolithically share Steinlight’s sentiments, they do curiously always seem to see things through a strict cost-benefit analysis of “Yes, but is it good for the Jews?” While they have no trouble recognizing the collective interests of their own people, they refuse to acknowledge that white gentiles have legitimate collective racial, ethnic and cultural interests of our own. In fact, they seem to insist on pathologizing the conveyance of any such sentiments or beliefs on our part.

With this in mind, I assert that Esther Schor closes her book on Emma Lazarus in a most frustrating fashion. She states that:

Emma Lazarus did what America’s makers have always had to do, be they the children of religious refugees, slaves, Native Americans, or immigrants: not surrender themselves to America, but leave their mark on it. In works like the cherished “New Colossus” and the neglected “Little Poems in Prose,” in the great poem of her life, she remade America in the image of a Jewish calling—a mission to repair the world.[34]

If it’s venerable that Emma Lazarus “remade” America in the image of a “Jewish calling,” then why are people upset that white Europeans remade North America into our calling? If we are to celebrate “not surrendering to America, but [leaving] their mark on it”, then why are many Jews so upset with Palestinians who refuse to surrender to Israel?

The Jewish concept of repairing the world also known as tikkun olam is described by some as the “idea that Jews bear responsibility not only for their own moral, spiritual, and material welfare, but also for the welfare of society at large.” But why is this mindset praised whereas “The White Man’s Burden” and “La Mission Civilisatrice” are vilified?

I won’t claim that Judaism doesn’t have a wide array of thought and disagreement on a number of topics including tikkun olam and the Noahide laws, but Maimonides, a renowned Jewish philosopher whose teachings on the Talmud are highly regarded, once said that:

Moses our Teacher was commanded by the Almighty to compel the world to accept the Commandments of the Sons of Noah. Anyone who fails to accept them is executed. Anyone who does accept them upon himself is called a Convert Who May Reside Anywhere. He must accept them in front of three wise and learned Jews. However, anyone who agrees to be circumcised and twelve months have elapsed and he was not as yet circumcised is no different than any other member of the nations of the world.

Let’s return to the topic of the so-called “Russian refugees,” of whom Emma was so found. Why were Russian gentiles persecuting the Jews in the 1880s? As it turns out, a young Russian contemporary of Emma’s wrote an article on this very topic. Zénaïde Alexeïevna Ragozin reveals in her 1881 Century Magazine piece, Russian Jews and Gentiles, that the Russian Jews had been abusing the local gentiles via the Qahal, a semi autonomous system of governance for Jews within non-Jewish societies. Technically, Nicholas I of Russia, had it abolished in the 1840’s, but Jewish apostate, Jacob Brafman, who had converted to Russian Orthodox Christianity insisted that the practice continued in secret. Ragozin quotes him in her article which I will now quote in a slightly altered form for clarity to modern readers.

[He writes that Jews view the] Gentile population of its district as ‘its lake’ to fish in, the Kahal proceeds to sell portions of this strange property to individuals on principles as strange. To one uninitiated in Kahal mysteries, such a sale must be unintelligible. Let us take an instance. The Kahal, in accordance with its own rights, sells to [a Jew] a house, which, according to the state laws of the country, is the inalienable property of [a Gentile], without the latter’s knowledge or consent. Of what use, it will be asked, is such a transaction to the purchaser? The deed of sale delivered to him by the Kahal cannot invest him with the position which every owner assumes toward his property. [The Gentile] will not give up his house on account of its having been sold by the Kahal, and the latter has not the power to make him give it up. What, then, has the [Jewish] purchaser acquired for the money paid by him to the Kahal? Simply this: he has acquired khazaka—i.e., right of ownership over the house of the [Gentile], in force whereof he is given the exclusive right, guaranteed from interference or competition from other Jews, to get possession of the said house, as expressly said in the deed of sale, ‘by any means [whatsoever.]’ Until he has finally succeeded in transferring it to his official possession, he alone is entitled to rent that house from its present owner, to trade in it, to lend money to the owner and other Gentiles who may dwell in it—to make profits out of them in any way his ingenuity may suggest. This is what is meant by khazaka. Sometimes the Kahal sells to a Jew even the person of some particular Gentile, without any immovable property attached. This is how the law defines this extraordinary right, which is called meropiè: ‘If a man [meaning a Jew] holds in his power a Gentile, it is in some places forbidden to other Jews to enter into relations with that person to the prejudice of the first; but in other places it is free to every Jew to have business relations with that person, for it is said that the property of a Gentile is hefker [free to all], and whoever first gets possession of it, to him it shall belong.[35]

Rather than blame so-called “antisemitism” entirely on irrational jealousy, hatred, or religious intolerance on the part of gentiles, it seems much more reasonable to entertain the notion that aggregate, or subsets of, Jewish behaviors have played a significant role in periodic “antisemitic” reactions throughout the ages.

Whatever the case, Emma Lazarus certainly was not the woman modern Jewish advocates and others assert she was. Not only did Emma hijack and taint the meaning of the Statute of Liberty, but her modern proponents often misrepresent and reorient her character for modern political aims.

Emma was a staunch Jewish identitarian whose motives were almost wholly particularistic in nature. She drew on a long, rich historical Jewish tradition and in doing so she often saw her American hosts, Russian gentiles, and the ancient Romans and Greeks as analogues for the “Seed of Haman.” She saw America as a strange land, and she sought to reimagine the world around her into one that was more amenable to her Jewish sensitivities and interests.

By Wilhem Ivorsson