This article was written by Ethan Young and originally published at American Institute For Economic Research

In North America and Europe, it has become abundantly clear that Covid-19 and the lockdowns that followed have devastated society. In the United States, unemployment is through the roof and 2020 saw the largest economic contraction in modern history. Social and cultural depression continue to weigh down society as restaurants close, the arts are stunted, and everything that it means to be human is taken from us.

We have plenty of data to paint a picture of the devastation in countries like the United States but there has been little analysis done in developing countries, more than likely due to lack of infrastructure. We know that many developing countries closed their economies in response to Covid-19 but we are unsure of how they fared.

In particular, developing countries likely do not have the same support structures be it private or public as countries like the United States do. They cannot simply print trillions of dollars to finance quantitative easing policies to prop up the stock market or send stimulus checks to ailing citizens. They also likely lack the private safety nets created by nonprofits and the general flexibility of an advanced business sector. One can only imagine the damage economic depression would bring upon such communities.

That was until a team of researchers published a study with the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The study provides a glimpse into the extent of the damage caused by the economic contraction in Africa, Asia, and South America. It details how living standards have fallen due to decreased access to basic needs such as food, unemployment, and the likely long-term consequences that will arise. Much like how in the United States there has been a noted correlation between economic shocks and decreases in life expectancies, we can expect similar if not worse consequences in developing countries.

It is worth noting, to be fair to the intent of the authors, that they are not making a judgment that the economic damage they note is in part or fully due to lockdown policies. Either way, it should be abundantly clear to everyone that the economic damage that has been wrought on societies across the world is not simply a minor inconvenience. It is a serious problem that has led to long-term as well as short-term adverse consequences in affluent countries like the United States and likely worse consequences for those who live in developing countries.

The Study

The methodology for the study made use of a series of household surveys conducted via phone calls in different developing countries. The authors explain,

We assemble evidence from over 30,000 respondents in 16 original household surveys from nine countries in Africa (Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, Sierra Leone), Asia (Bangladesh, Nepal, Philippines), and Latin America (Colombia).

They noted that,

The data paint a consistent picture: The economic shock and attendant disruptions to livelihoods during the early stages of pandemic appear to be large across a range of populations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The scale of the disruption may even exceed the effects that economists have documented in other recent global crises, including the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the 2008 Great Recession, and the Ebola outbreak of 2014.

AIER has frequently noted that large-scale lockdown policies have no precedent in the history of public health policy, which may explain why the economic contraction was so large compared to previous years. I would contend that consciously working to shut down businesses rather than attempting to support them, as would be the case in a normal recession, leads to highly unusual economic damage.

After analyzing the household data the authors report,

A full 50 to 80% of sample populations in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone report income losses during the COVID-19 period. If these effects persist, then they risk pushing tens of millions of already vulnerable households into poverty.

Such income reductions have then led to subsequent food insecurity and even the reduction of net wealth as families are forced to sell off their belongings. On this the authors note,

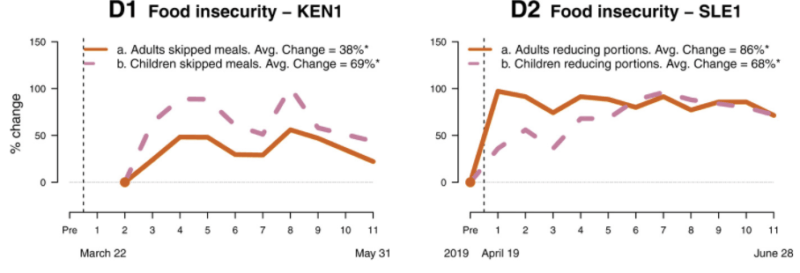

By April, many households were already unable to meet basic nutritional needs. For example, 48% of rural Kenyan households, 69% of landless agricultural households in Bangladesh, and 87% of rural households in Sierra Leone were forced to miss meals or reduce portion sizes to cope with the crisis. Comparing to preexisting baseline data verifies that these levels greatly exceed the food insecurity normally experienced at this time of year.

It was clear before the pandemic that developing countries such as the ones in this study were already dealing with these issues. Now they have only been exacerbated, likely reversing years of hard work to combat poverty and hunger.

Provided below are graphs from the study detailing the recorded increases in food insecurity in Kenya and Sierra Leone. It is important to note that like all studies there are limits to this data and its accuracy as household surveys can only provide so much information.

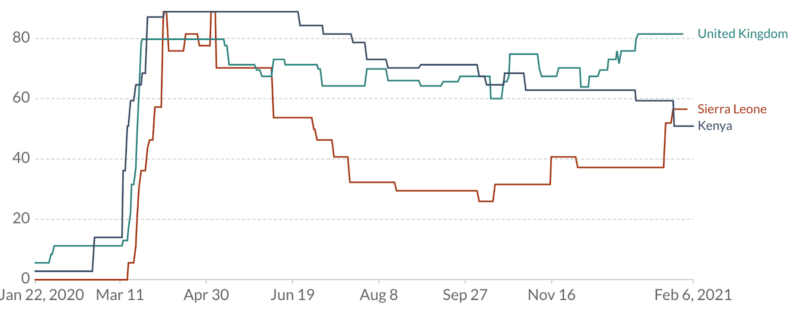

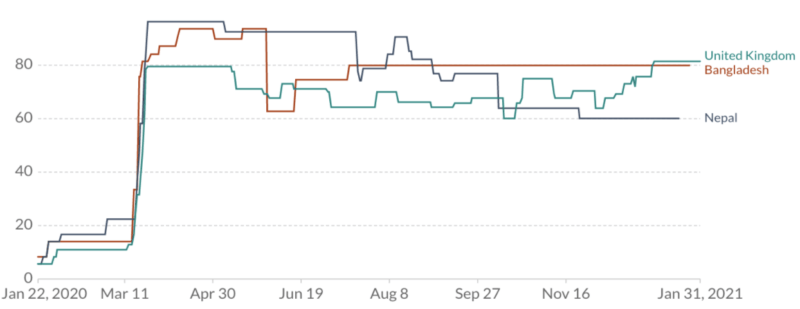

For reference, provided below are the stringency indexes (Our World in Data) for both countries with the United Kingdom as a comparison. The UK is known to have one of the strictest lockdowns and also one of the hardest hit for Covid-19. It seems reported food insecurity in both countries seems to mirror the timeline of the implementation of lockdowns. Of course, there could be a variety of factors at play such as the possible correlation of lockdown severity and the spread of Covid-19 and the individual circumstances unique to each country.

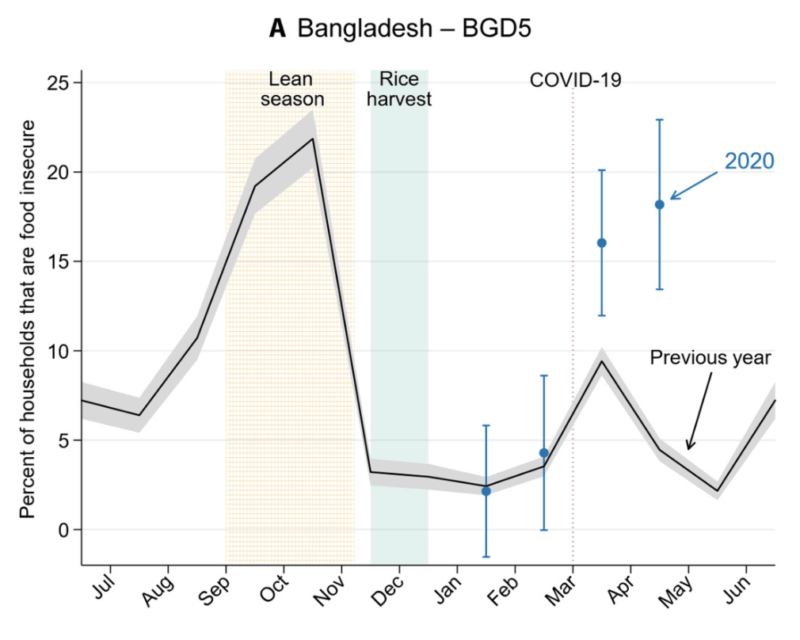

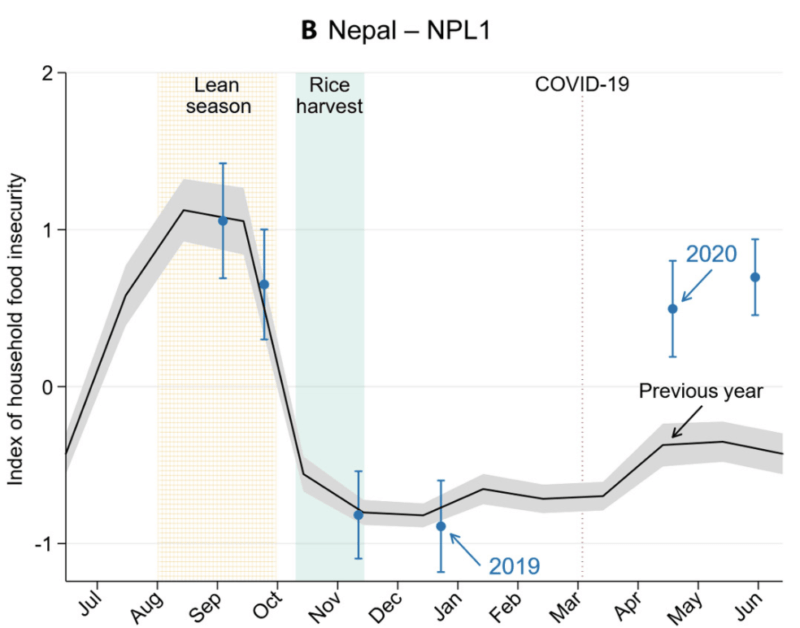

The study also charts the levels of food insecurity in relation to historical harvest cycles in Nepal and Bangladesh. It notes that there is a clear and unprecedented increase in food insecurity even though the pandemic occurred after the rice harvest periods. It notes that historically food insecurity has always increased in the “lean season” which is the period preceding the rice harvest. However, the pandemic occurred after the harvest so the sharp increase in food insecurity cannot be attributed to the historic patterns of food scarcity. It is clearly a result of Covid-19 and the lockdowns that followed. Provided below are the graphs included in the study. The blue lines represent the most recent cycle which clearly follows historic trends until the March-April period of 2020 which is when most of the world entered strict lockdowns.

Provided above are the stringency indexes for both countries with the United Kingdom for context, again being a country that implemented highly strict lockdowns. The food insecurity spikes were reported during the March-April period in both Nepal and Bangladesh which directly follows the implementation of lockdowns.

Across all the countries in the study, substantial decreases in standards of living arising from food insecurity, unemployment, income reduction, and a lack of access to markets have had devastating results. The authors warn that,

The economic crisis precipitated by COVID-19 may become as much a public health and societal disaster as the pandemic itself. The link from severe economic crisis during childhood to subsequent deterioration in adult health, nutrition, education, and earnings capacity has been demonstrated in many contexts.

As explained earlier and often repeated by AIER, there are serious consequences that come from economic shocks that affect everything from mental health to life expectancies here in America. One can only imagine how much more devastating such economic disruption has been in developing countries that lack the infrastructure and resources to support those in need.

Key Takeaways

The global poor, especially those living in developing countries, have always suffered from a long list of disadvantages, whether it be lack of social capital, technology, infrastructure, or food insecurity. These problems are only exacerbated when their societies, which are already in poor shape, are abruptly shut down.

Although the authors of the study do not make a definitive judgment on whether these economic shocks have become as severe as they are because of lockdowns, it is clear that shutting down economies, be it voluntary or involuntary, is a dangerous policy. It affects the global poor as well as the global elite and it seems that the poorer countries have seen a dangerous decline in living standards which will have lasting consequences that are a public crisis in and of themselves.

Regardless of where one stands on lockdowns, it should now be abundantly clear that economic hardship is not a minor inconvenience and action must be taken to alleviate existing damage and to prevent the further exacerbation of existing calamity.

The post Lockdowns Have Devastated the Global Poor appeared first on Alt-Market.us.