New documents show that the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) still owes $137 million dollars to Genel Energy PLC, an Anglo-Turkish company that began exploiting Kurdistan’s oil fields just prior to the commencement of the US occupation of Iraq. The KRG owes the company this amount despite already paying Genel Energy $33.7 million dollars in June this year.

How international oil companies entered Iraqi Kurdistan

The development of hydrocarbons in Iraqi Kurdistan has been of tremendous importance for the political economy of the region. It has also been one of the main factors in allowing the Kurdish region the autonomy it enjoys today.

Exploitation of oil and gas in the region known as the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), however, has not always been this regularized.

A peek into recent history shows that oil exploration in the areas now part of the KRI were limited prior to 2004. Iraq’s assets had been fully nationalized by 1975, and the Baath government of Saddam Hussein was simply not interested in developing the regions primarily inhabited by Kurds.

Moreover, Kurdish opposition to central government activities in their areas were often met with acts of sabotage.

Yet there has been extensive knowledge of the hydrocarbon resources present in the region for well over a century. The Chemchemal gas field was discovered as early as 1921, the Khor Mor gas field in 1953, the Demir Dagh oilfield in 1960, and the Taq Taq oilfield in 1978.

The earliest well to be drilled – called Chia Surkh – has existed since 1901.

Between 1991 and 2004, during the Kurdish struggle for independence, there was little exploration in Taq Taq for local use, but with sanctions imposed on Iraq by the UN, and amidst the uncertain political and security situation, no international company could operate in the region.

Certainly, the Kurds had neither the knowledge nor the resources to do so.

A Turkish company grabs oil rights right before the Iraq invasion

The 2003 US invasion of Iraq and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein led to an influx of international companies into Kurdistan. Among these oil and gas operators were the Swiss Group Addax, Norway’s DNOASA, UAE’s Dana Gas and Crescent Petroleum, and Canada’s Western Zagros Resources.

Exploration of Iraqi-Kurdish oil fields started in 2004, and was enlarged under Natural Resources Minister Ashti Hawrami who was appointed in 2006.

With one exception. Several months before the March invasion of Iraq, a little-known company crept into Iraqi Kurdistan to sign a contract with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP).

The company, Genel Energy, backed by major Turkish investors, quietly signed a production-sharing contract for the Taq Taq field in July 2002, and amended it in January 2004. It was the first oil company to build a new oil well in Iraqi Kurdistan after the fall of Saddam Hussein.

In fact, Genel Energy was founded in 2002 for this precise purpose by the owner of Çukurova Holding, Mehmet Emin Karamehmet, and his business partner Mehmet Sepil. In 2011, Genel Energy merged with Nathaniel Rothschild’s Vallares.

This now Anglo-Turkish company retained the name Genel Energy upon the $2.1 billion dollar merger.

The next year, a secret energy deal was struck between Turkey and the KRG, to distance their activities from the central government in Baghdad, which is constitutionally responsibility for all Iraqi oil. The two conspired to bypass a traditional pipeline and build their own, so they could directly transport around one million barrels per day (at the time, a third of Iraq’s oil output) of Iraqi oil from Genel’s Kurdistan fields into Turkey. While awaiting the new pipeline, Genel Energy reportedly transported 500 trucks each day by land to the Turkish border.

The former British Petroleum (BP) chief executive running Genel Energy was followed in this scheme by major US oil companies Exxon Mobil, Chevron and others, bolstering Kurdish plans to break Baghdad’s control over oil shipments from the Kurdistan region.

A driving force behind these maneuvers was Turkish President Erdogan’s determination to reduce his country’s dependence on Russian and Iranian oil imports and seek cheaper sources. In early 2013, Erdogan made a deal with KRG Prime Minister Nechivan Barzani to increase Turkish stakes in Kurdish oil and negotiate terms for the direct pipeline to Turkey.

It was a blow to Iraq’s sovereignty, as the Turkish-Kurdish agreement would further diminish Baghdad’s oversight of its natural resources and its access to the funds derived from oil sales.

Today, Genel Energy owns rights in at least six production-sharing contracts (PSCs) in Iraqi Kurdistan, and is the largest oil producer in the region. It is the only company that holds more than one production license in the region, making the KRG’s cooperation with the Turkish oil company one of a kind. Genel Energy’s only other activities can be traced to Somaliland, another country that Turkey attempts to control.

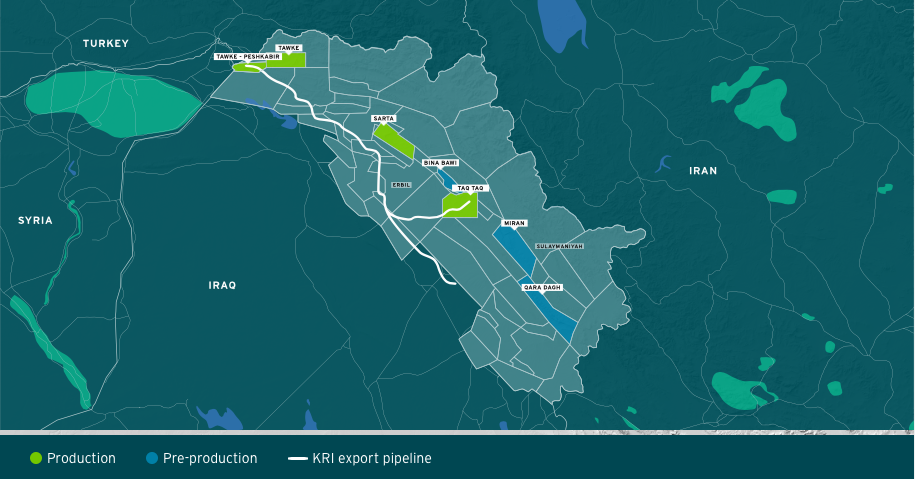

Map of Genel Energy’s operations in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

The Baghdad–Erbil oil dispute

Disagreements between Baghdad and the KRG over oil production have been one of the most persistent reasons for Iraq’s lack of unity today. And there are three reasons why a lasting resolution of this dispute appears out of reach.

The first is legal, and it concerns the right to export oil under Iraq’s federal system. Iraq’s constitution, ratified in 2005, states that the country’s oil is “owned by all the people of Iraq,” and therefore oil revenues should be shared throughout the nation. The KRG obviously intends to have its cake and eat it too – as well as share much of it with the Turks.

The second is distrust, rooted in the KRG’s desire to control independent revenue streams free from Baghdad’s whims, and the latter’s reluctance to bankroll the Kurdish separatism that reared its ugly head in Erbil’s 2017 referendum.

The third is financial, as ties and dues concerning oil budget are further complicated by KRG obligations to creditors who lent the region billions of dollars against future oil deliveries. These debts actively threaten Iraq’s economy.

By 2014, the KRG had begun to unilaterally export oil via pipeline through Turkey. Soon it added Kirkuk’s fields – after Iraqi forces withdrew from the area during the ISIS onslaught – boosting exports to over 500,000 barrels per day (bpd). The Baghdad–Erbil clash reached its height in 2017 due to the referendum that threatened to sever an “independent” Kurdistan from Iraq.

Immediately after the referendum, in which Erbil attempted not only to politically split with Baghdad, but also unjustly claimed Kirkuk’s oilfields as its own, federal forces and allied militias advanced to reclaim Kirkuk and its oilfields.

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) had been emboldened by the stream of income it received through Anglo-Turkish Genel Energy and other major US oil companies active in the region. Neither Turkey nor the US profit from a strong, unified and independent Iraq.

Turkey’s constant violations of Iraqi sovereignty

It is not only KRG’s oil dealings that frustrate the Iraqi government. Turkey’s repeated violations of Iraqi sovereignty have also heightened tensions between Baghdad and Erbil.

Turkey not only shows little regard for Iraqi sovereignty in its relentless cross-border airstrikes and ground offensives against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), but it also undermines Iraqi territorial integrity by establishing dozens of Turkish military bases, some of them a mere 30-40 kilometers from its border. There is little doubt it has the confidence to act this way, in no small part because of the military and political cover extended by the KRG in northern Iraq.

Ankara’s goals are more than military ones, however. Turkey seeks to dominate Erbil’s political course and KRG’s trade sector through institutions such as Çukurova Holding. This group of companies is not only active in the oil sector, but holds the largest stakes in KRG’s chemicals, paper, packaging, steel and textiles sectors.

It only takes a glance at Zakho’s border crossing or a brief stroll through the bazaar in Erbil or Duhok to realize how large, in fact, Turkey’s footprint is in Iraq today. Ankara’s influence in the KRG oil sector is only the tip of this iceberg.

And the Barzani family has always been eager to let the Turks in.

Allegations of a secret deal

It is no secret that the leading family of Iraq’s Kurdistan region, the Barzani family, and their political party, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), have had a very close relationship with Turkey for decades.

Starting in 1992, and continuing through to 1998, Turkey helped the KDP gain control over the largest part of the Iraqi-Kurdish region. In return, the KDP has never opposed Turkey’s targeting of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) on its territory. The PKK is a popular Kurdish socialist-nationalist political and military movement now primarily based in the Kurdish-majority regions of southeastern Turkey and northern Iraq, and has been a thorn in Turkey’s side for decades.

Relations between Turkey, which has persecuted Kurdish populations both inside and outside its borders, and the KDP are not, however, focused only on a political and security alliance. There are collaborations in every field. For years, there has been word of a secret 50-year deal between Turkey and the KDP, although it remains unclear what precisely this agreement entailed.

The establishment of Genel Energy just prior to the invasion of Iraq, with the purpose of exploring and producing Kurdistan’s untapped oil resources, however, fits right into the history of stealthy deals between the two.

But their interests do not always converge, and it is not unheard of for Turkey and the Barzanis to play hardball against the other.

“One of the allegations made in the region is that $42 billion of the Barzani family money is in banks in Turkey,” says Iraqi-Kurdish politician Polat Bozan. “Barzani has invested $42 billion from Kurdistan’s oil in Turkey’s banks, and this is being used by Turkey against Barzani.”

According to Bozan, Turkey holds the Barzani family in an iron grip through the assets it has placed in Turkey’s hands. “It is certain that Kurdish oil is included in the agreement,” he says.

Genel Energy’s hold on Kurdistan oil

What is certain is that the Anglo-Turkish company, Genel Energy, holds the KRG in an iron grip, despite the latter’s recent attempts to break that hold.

In an August 20 statement, Genel Energy said it had received notice from the KRG Ministry of Natural Resources of its intention to terminate the Bina Bawi and Miran production-sharing contracts (PSCs).

The company said it sees “no ground” for such a move and that it will “take steps to protect its rights.”

The gas fields of Bina Bawi and Miran contain an estimated 14.8 trillion cubic feet of raw gas, which Genel Energy planned to export to a growing market in Turkey, according to Bloomberg.

It is unlikely these contracts will be effectively terminated, as the Kurdistan Regional Government still owes Genel Energy $137 million dollars, despite having repaid the company $33.7 million dollars in June this year. So Kurdistan, and therefore Iraq, will remain under financial duress for the foreseeable future, unless political currents shift significantly, and Baghdad takes the lead in shrugging off its 18-year NATO noose.

Statement concerning receipt of payments for KRI oil sales.