Various health problems reported by people after receiving one of the COVID-19 vaccine shots are more likely caused by the vaccines than being merely coincidental, according to an analysis of data from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS).

A deeper analysis of the data, however, indicates that many of the adverse effects are more than just a coincidence, according to Jessica Rose, a computational biologist who’s been studying the data for at least nine months.

“The safety signals being thrown off in VAERS now are off the charts across the board,” she told The Epoch Times.

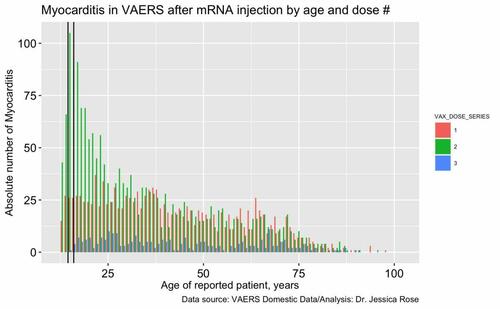

There are multiple ways to parse the data in order to flush out whether the causal link between an adverse event and the vaccination is real or illusory. For example, the vaccines usually come in two doses. A random adverse event unrelated to the vaccine should be dose agnostic. A stroke randomly coinciding with a vaccination shouldn’t be picky about which dose it was. In the VAERS data, however, a number of the reported problems are dose-dependent. Myocarditis in teenagers, for example, is reported several times more often after the second dose than after the first one. Following a booster shot, in contrast, the frequency is significantly lower than after the first dose, Rose found.

Other researchers and health authorities have already acknowledged that the shots are associated with an elevated risk of myocarditis, especially in teenage boys, though they usually also say the risk is low.

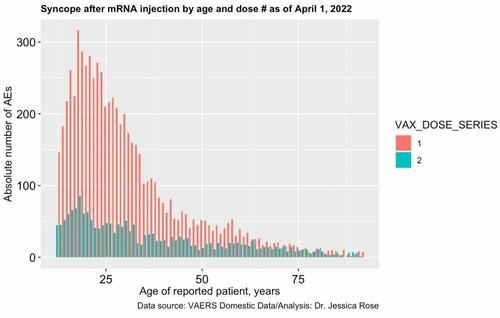

Yet dose-dependency shows up in the VAERS data for other problems too, including fainting and dizziness, which are more common after the first dose.

Rose acknowledged that statistical analysis seldom provides definitive answers. There could be, for instance, some unknown factor that leads to more reports of unrelated health events after the first or second shot. In her view, however, the data leans away from such a conclusion. Previous research showed that the majority of VAERS reports are filed by medical staff, who shouldn’t fail to report adverse events based on which dose is being administered. To Rose, it seems more likely that if people suffer health problems after an injection of a novel substance and if the problems substantially change between the first and the second shot, the substance probably had something to do with it.

“In lieu of being able to explain this happening for any other reason, it satisfies the dose-response point quite well, in my opinion,” she said of the myocarditis results.

As for why the reports dropped after the “booster” shots, she said she hasn’t found a definitive explanation. It could be that people who didn’t feel well after the first two shots would think twice about getting more. As such, those most at risk for an adverse reaction would be less likely to get the booster.

Rose arrived at the results after she evaluated the VAERS data from the perspective of the Bradford Hill criteria—a set of nine questions that are used by epidemiologists to determine whether any given factor is likely the cause of an observed health effect.

She said she found evidence to answer positively all of the questions.

Rose has encountered resistance in the establishment science circles when she first tried to publicize her analyses. Last year, right before her paper on VAERS myocarditis data was printed, the publisher pulled the paper for unclear reasons.