This heavily managed ‘market structure’ is far from equilibrium and extremely prone to instability.

The relentless melt-up in stocks offers ample evidence that the market is rock-solid and that any decline is an enormous opportunity to buy the dip. That this has worked splendidly for the past 13 years cannot be denied.

This doesn’t necessarily guarantee the next 13 years will merely be an extension of the same trend.The market’s sources of fragility and brittleness are well cloaked by low-volume melt-ups; these vulnerabilities only become visible in high-volume sell-offs such as 2020’s brief mini-crash.

To understand the fragility at the heart of the market, we must return to the Global Financial Meltdown of 2008-09 and former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan’s explanation of why he and all the other experts failed to understand the market’s vulnerabilities and thus failed to forecast the global crash.

Never Saw It Coming: Why the Financial Crisis Took Economists By Surprise (Dec. 2013 Foreign Affairs):

“The financial crisis that ensued represented an existential crisis for economic forecasting. The conventional method of predicting macroeconomic developments — econometric modeling, the roots of which lie in the work of John Maynard Keynes — had failed when it was needed most, much to the chagrin of economists. In the run-up to the crisis, the Federal Reserve Board’s sophisticated forecasting system did not foresee the major risks to the global economy. Nor did the model developed by the International Monetary Fund.”

In essence, Greenspan argued that the fancy models did not anticipate or capture human emotions in a financial panic. This is a remarkable confession, given the long study of panics and the wealth of research available on human emotions.

Greenspan then moved on to the real issue: liquidity–the bid to buy stocks–disappears:

“They (financial firms) failed to recognize that market liquidity is largely a function of the degree of investors’ risk aversion, the most dominant animal spirit that drives financial markets. But when fear-induced market retrenchment set in, that liquidity disappeared overnight, as buyers pulled back. In fact, in many markets, at the height of the crisis of 2008, bids virtually disappeared.”

In effect, Greenspan et al. assumed there would always be a pool of buyers willing to buy whatever stocks sellers were unloading. One potential pool of such buyers are those traders who bet on a market decline by selling short–selling shares at the top that they would buy back after a decline, pocketing the difference as profit.

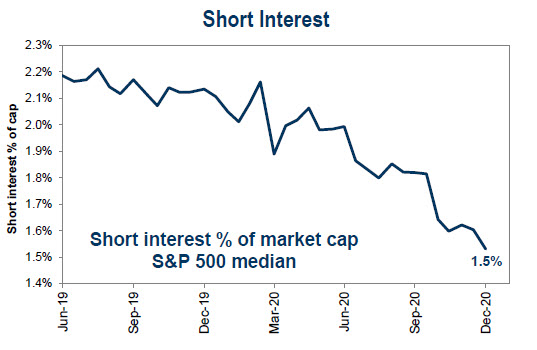

What Greenspan did not acknowledge in his mea culpa was central banks’ role in goosing markets so relentlessly that short selling dried up. Why bet on a market decline in a central-bank managed melt-up? Why lose money by betting against managers with trillions at their fingertips? So short interest declines to a negligible backstop against a crash–precisely the situation now as short interest has declined to recent lows (See chart below).

The other source of bids is buy the dip traders conditioned by the melt-up to aggressively buy every drop in the market. These buyers may be retail (individual) human speculators or they may be computers programmed to buy the dip. This buy the dip reaction (greed) was on display in 2020’s mini-crash, as every plunge was aggressively bought. However, each spike higher was soon sold (fear) and the market promptly fell to new lows.

Many of the buy the dip players are leveraged, meaning that they are using borrowed money (margin debt) to buy more stocks. Should the market drop instead of rebounding, their account will fall below minimum requirements and they will have to add cash or sell stocks. When buy the dip fails, those with margin calls add to the selling.

Most of the trading volume nowadays is generated by computers–called algos because they’re programmed to trade based on algorithms that have been tweaked by very smart people and machine learning.

The problem with algos is it’s difficult to program for black swans or unpredictable rogue-wave monstrous moves. So the prudent programmer takes the computer offline to avoid the risk of the algo making a trading decision in a rare and thus difficult to model crisis that ends up wiping out the financial firm.

This is why liquidity–traders willing to buying stocks at the bid–dries up incredibly fast.Short sellers are such a thin slice of the market now that their buying is little more than a sand castle in a tsunami. Algos programmed to escape a decline by selling pile in while algos programmed to buy the dip quickly reverse and sell when the expected rally fails to materialize. As the rogue wave washes away all the sand castles, the algos are taken offline and liquidity goes to zero.

This is how the price of oil crashed to a negative number in the 2020 mini-crash. The market went bidless, meaning there were no buyers at any price. In Street jargon, trying to buy on the way down is called catching the falling knife: the knife is in free-fall, and buying in at what you guess is the bottom can turn out to be only halfway down the decline. Oops.

This is the consequence of managing markets to only melt up and reversing every decline with trillions in freshly created “money.” The market structure has been stripped of actual market dynamics, leaving it exquisitely fragile and brittle.

Put another way, this heavily managed market structure is far from equilibriumand extremely prone to instability. All this is hidden behind the curtain, where the managers are furiously pulling levers and pushing buttons to maintain the illusion of stability needed to forecast melt-ups are forever.

What’s going on behind the curtain? Few seem to care. Eventually they will, but like Greenspan in 2013, it will be long after the losses have been wept over.

If you found value in this content, please join me in seeking solutions by becoming a $1/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

My new book is available!A Hacker’s Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet 20% and 15% discounts (Kindle $7, print $17, audiobook now available $17.46)

Read excerpts of the book for free (PDF).

The Story Behind the Book and the Introduction.

Recent Podcasts:

AxisOfEasy Salon #36: Democratizing Stonk Market Manipulation (1:03 hrs)

The Roundtable Insight: Charles Hugh Smith on Is 2021 an Echo of 1641? (26 min)

My recent books:

A Hacker’s Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Pathfinding our Destiny: Preventing the Final Fall of Our Democratic Republic($5 (Kindle), $10 (print), (audiobook): Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake$1.29 (Kindle), $8.95 (print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 (Kindle), $15 (print)Read the first section for free (PDF).

Become a $1/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Matthew W. ($50/month), for your beyond-outrageously generous pledge to this site — I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Frederick B. ($5/month), for your massively generous pledge to this site — I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |