Hectic in-person parleys of Quad foreign ministers – of the US, Japan, Australia and India – in Melbourne on Friday are juxtaposed by the triangular three-day deliberations of special representatives on the denuclearization of North Korean – from the US, Japan and South Korea – in Honolulu.

While the former has a whole range of issues on the agenda including preparing for the next Quad leaders’ summit in May, the latter, focused on North Korea, will conclude on Saturday with the respective foreign ministers issuing a final statement.

On the way from Melbourne to Hawaii, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken is also scheduled to stop by in Fiji to meet with a number of Pacific island leaders, and that meeting is expressly aimed at weaning them away from the economic lure of China’s aid and investments.

At the very outset, being hurriedly put together in the backdrop of seven missile tests by North Korea last month followed by the February 4 joint statement of Presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin and in the midst of the continuing Covid-19 pandemic, the Afghan and Ukraine crises, and South Korea’s presidential election campaign, this much-needed revival of talks is most likely to achieve just that, revival.

Varying visions

If anything, meetings of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue over the last four years have gradually laid bare not just the group’s ever-expanding charter of multiple sub-groups but also increasing variation in the four states’ respective visions. While the US continues to push its countering China agenda on the Quad, India, Japan and Australia – in that order – have been far more cautious of toeing the line on that sentiment.

India and Japan share enormous trade and investment ties as well as border disputes with China that have witnessed increasing tensions in recent times. At he same time, the US has become far more entangled in the Ukraine crisis, resulting in its becoming less engaged with the Indo-Pacific region.

India is a huge nation and market and a newfound friend of the US. But India has also been most vocal against Indo-Pacific militarization or the region becoming an exclusive club of a few nations, openly inviting China and Russia to be part of the Indo-Pacific discourse.

Also, in spite of much-hyped nuclear and defense deals, no US nuclear technologies have arrived in India, and the US is India’s fourth-largest supplier of military equipment after Russia, Israel and France. If anything, the US has warned India of sanctions for its purchase of Russian S-400 missiles.

South Korea is another critical ally of the US where the domestic situation is currently in flux. Since presidents in South Korea serve only one term in office, Moon Jae-in is not contesting the March 9 election, and both mainstream political parties – the Democratic Party of Korea and the People Power Party – have nominated known right-wing candidates, one of whom will be the next occupant of the Blue House in Seoul.

Neither of these two candidates is expected to match up to Moon Jae-in’s dedication for exploring rapprochement in inter-Korean relations.

Being a dovish liberal and son of a war refugee, Moon had staked his presidency on resolving tensions with Pyongyang and worked hard on facilitating two summits between then-US president Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un. Lately he has been most vocal expressing his anxieties regarding the revival of North Korea’s weapons program. But in spite of all these merits, engaging an outgoing lame-duck regime carries little meaning, if at all.

Likewise, the Quad leaders’ summit has been scheduled for May in Tokyo, and it overlaps with Australia’s federal elections, where opinion polls have indicated little likelihood of Prime Minister Scott Morrison and his coalition retuning to power.

It is against this backdrop that these two foreign ministers’ confabs – the Quad and the triangle – are expected to finalize details for the third (second in person) Quad leaders’ summit while also finding an effective strategy to slow if not eliminate North Korea’s nuclear and missiles programs.

American overstretch

The US, which lies at the very center of these initiatives, seems far too overstretched. The Joe Biden administration’s ambitious “America is back” mantra has been dwarfed by its precipitous exit from Afghanistan followed by its slip into the Ukraine crisis, thus stretching its engagements far too wide and thin.

For instance, while working to revive its Indo-Pacific Quad, the US last year also launched another Quad in West Asia – comprising itself, India, Israel and the United Arab Emirates – while its efforts to revive the pivotal Iran nuclear deal have been pushed to the back burner.

The most important lesson of the continuing Ukraine crisis is how the US has lost its grip on the NATO alliance that undergirds its global leadership. The aggressive tone of the US and its closest ally the UK is no longer supported by several members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

This week saw French President Emmanuel Macron emerge as a star interlocutor, followed by German Chancellor Olaf Sholz trying to save the US$11 billion Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which is set to double its gas imports from Russia. Sholz just hosted national leaders of the Baltic states and dissuaded Estonia from supplying weapons to Ukraine.

Not to be left behind, even Prime Minister Boris Johnson is visiting Brussels and Warsaw and sending his foreign and defense secretaries to Moscow. Hungary’s seasoned prime minister, Viktor Orban, last week visited Moscow for his 13th meeting with President Putin and said there is no need for NATO soldiers to be stationed in his country.

Even Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has called the responses of Boris Johnson’s and Joe Biden’s administrations unnecessarily alarming and impractical.

Another quickly stitched together security arrangement, AUKUS, has also created irritations between the US and a powerful NATO ally, France.

But all this flurry of foreign ministers’ meetings has meant that the Quad is no longer viewed by China as an Asian NATO, while North Korea feels emboldened by the triangle presenting itself as an alternative to Six Party Talks.

The recent joint statement by Xi and Putin underlines their new focus on AUKUS, recognizing that the Quad has shifted its focus toward the softer issues of the pandemic, climate change, critical technologies, cybersecurity and so on while China-centric power posturing in the Indo-Pacific has been outsourced to AUKUS.

But it is pertinent to ask for how long, in the face of China and Russia upgrading their cooperation, globalizing Britain, assertive France, indigenizing Australia, or multi-aligned India will continue to see their own national interests perfectly aligned with that of the US. Increasingly visible variations in their perceptions call for the US revisiting its arguments, alignments, and expectations.

Dr Swaran Singh is professor of diplomacy and disarmament at the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi; adjunct senior fellow at The Charhar Institute, Beijing; senior fellow, Institute for National Security Studies Sri Lanka, Colombo; and visiting professor, Research Institute for Indian Ocean Economies, Kunming (China).

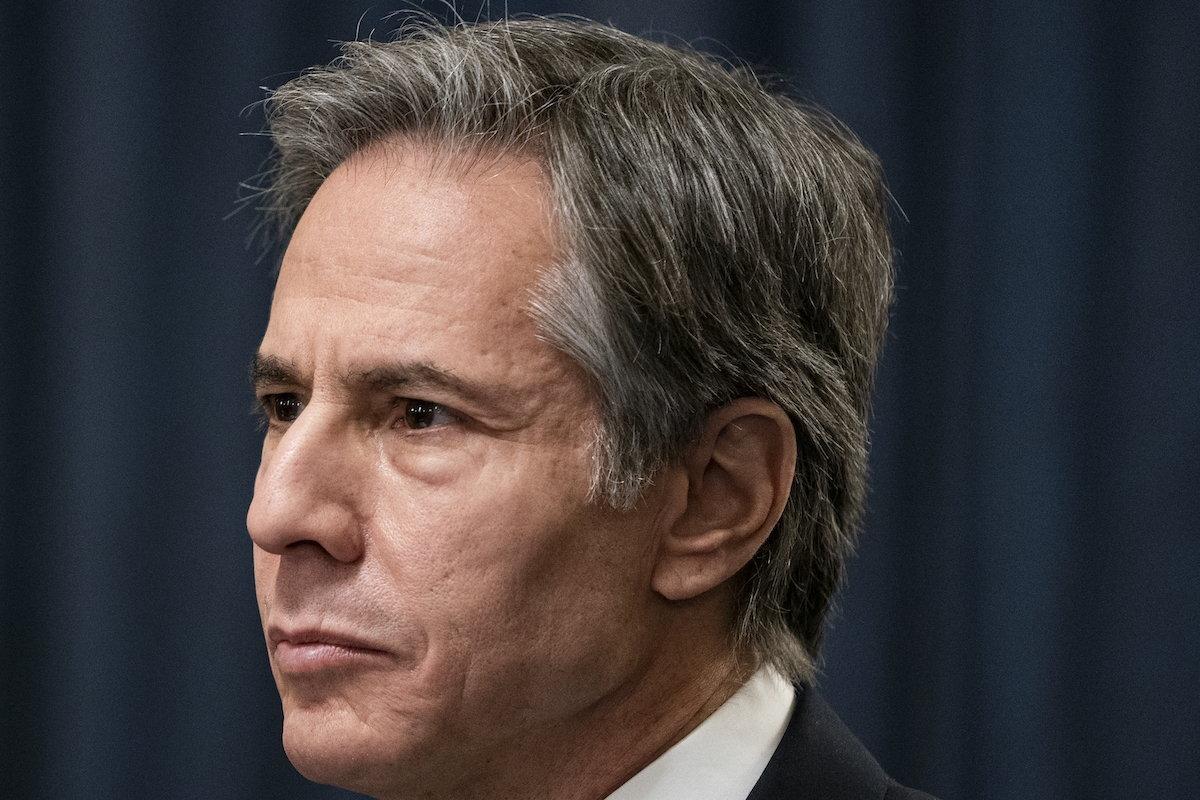

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken is dealing with the complexities of holding America’s Indo-Pacific alliances together. Photo: AFP / Alex Edelman

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken is dealing with the complexities of holding America’s Indo-Pacific alliances together. Photo: AFP / Alex Edelman