Masses of Haitians have protested intermittently and countrywide since August. They are reacting to high costs – thanks to the International Monetary Fund – and to shortages of food and fuel. Banks and stores are closed. Students are involved. Labor unions have been on strike.

The pattern has repeated intermittently for ten years. Demonstrators have consistently pointed to corruption and demanded the removal of top leaders, specifically Presidents Michel Martelly and Jovenel Moïse and now de facto prime minister Ariel Henry. Meanwhile, ordinary Haitians are dependent, marginalized, and oppressed.

This report is about violence aggravating a grim situation and about the reaction of foreign powers, including the United States, to Haiti’s instability and violence. In the background is a history of U.S military interventions and other intrusions that have trashed Haiti’s national sovereignty and, with an assist from Haiti’s elite, undermined ordinary people’s control of their lives.

Also relevant, it seems, are both racist attitudes originating from the slave system’s central role in developing the U.S. economy and residual discomfort with enslaved Haitians going free and setting up their own republic.

Haitians are suffering. Presently, 40 percent of the people are food insecure. Some 4.9 million of them (43%) need humanitarian assistance. Life expectancy at birth is 63.7 years. Haiti’s poverty rate is 58.5%, with 73.5 % of adult Haitians living on less than $5.50 per day.

Electoral politics is fractured. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton arranged for Michel Martelly’s run for the presidency in 2011. President Moïse in 2017 was the choice of 600,000 voters – out of six million eligible voters. He illegally extended his presidential term by a year. There have been no presidential elections for six years, no elected mayors or legislators in office for over a year, and no scheduled elections ahead.

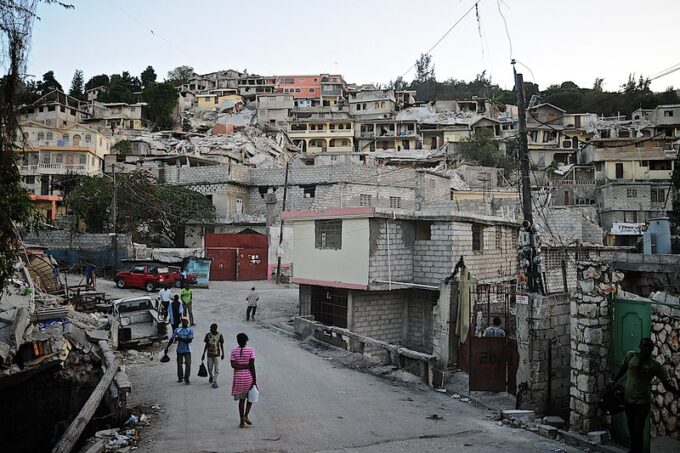

Gangs have had a presence and their violence has intensified. Jovenel Moïse’s election in 2017 prompted turf wars, competing appeals to politicians, narcotrafficking, kidnappings, and deadly violence in most cities, predominately in Port-au-Prince. Violence accentuated after Moise’s murder in July 2021. Hundreds have been killed and thousands displaced, wounded, or kidnapped.

The U.S. Global Fragility Act of 2019 authorizes multi-agency intervention in “fragile” countries like Haiti, the U.S. military being one such agency. The influential Council of Foreign Relations (CFR) wants U.S. soldiers to be instructing Haitian police on handling gangs. Luis Almagro, head of the Organization of American States, calls for military occupation. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres wants international support for trainingHaitian police.

Former U.S. Special Envoy to Haiti Daniel Foote weighs in with a choice: either “send a company of special forces trainers to teach the police and set up an anti-gang task force, or send 25,000 troops at some undetermined but imminent period in the future.” The Dominican Republic has stationed troops at its border with Haiti and calls for international military intervention in Haiti.

Meanwhile, foreign actors intrude as Haitians try to reconstruct a government. Their tool is the Core Group, formed in 2004 following the U.S.-led coup against progressive Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The Core Group consists of the ambassadors of Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Spain, United States, and representatives of the United Nations and Organization of American States.

Haiti’s government is in the hands of Ariel Henry, whom the Core Group approved as acting prime minister, overruling Moïse’s choice made before he died. Henry, a U.S. government favorite, may be complicit in Moïse’s murder.

Henry insists he will arrange for presidential elections. The prevailing opinion holds that conditions don’t favor elections any time soon.

The Core Group backs an important agreement announced by the so-called Montana Group on August 30, 2021. It provides for a National Transition Council that would prepare for national elections in two years and govern the country in the meantime. The Council in January 2022 chose banker Fritz Jean as transitional president and former senator Steven Benoit as prime minister. They have not yet assumed those jobs.

The Montana group consists of “civil society organizations and powerful political figures,” plus representatives of political parties. One leader of the Group is Magali Comeau Denis who allegedly participated in the U.S-organized coup that removed President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004. Ariel Henry worked with the Democratic Convergence that in 2000 was plotting the overthrow of President Aristide.

The CFR wants the U.S. government to persuade Henry to join the Montana Group’s transition process. Daniel Foote supports the Montana agreement because it shows off Haitians acting on their own. Recently some member organizations have defected, among them the rightwing PHTK Party of Henry and of Presidents Martelly and Moïse.

The weakness of Haiti’s government in the face of dictates from abroad was on display during President Moïse’s era. The perpetrators of his murder, who had been recruited by a Florida-based military contractor, were 26 Colombian paramilitaries and two Haitian-Americans. Their motives are unclear and there is no apparent movement toward a trial.

Moïse, the wealthy head of an industrial-scale agricultural operation, became president through fraudulent elections in 2017. He was the target of massive protests in 2018. Prompting them were fuel and food shortages and revelations that Moïse and others had stolen billions of dollars from the fund created through the Venezuela’s PetroCaribe program of cheap oil for Caribbean nations.

Foreign governments, the United States in particular, may be on the verge of intervening in Haiti. But the ostensible pretext, gang violence, turns out to be muddled. Progressive Haitian academician and economist Camille Chalmers makes the point. He claims that “gangsterism” in Haiti actually serves U.S. purposes.

Interviewed in May 2022, Chalmers explains that the “principal [U.S.] objective is to block the process of social mobilization, to impede all real political participation … through these antidemocratic methods, through force using the police … and above all these paramilitary bands.” Terror is useful for “breaking the social fabric, ties of trust, and any possible resistance process.”

By means of gang violence, the Haitian people “are removed from any political role and the economic project of plundering resources from the country is facilitated.” Also, Haiti becomes “an appendage of the interests of the North Americans and Europeans.” Chalmers refers to gold deposits on Haiti’s border with the Dominican Republic and big investments by multinational corporations.

He sees a bond between reactionary elements in Haiti and the gangs. The gangs “have financing and weapons that come from the United States. Many of their leaders are Haitians who have been repatriated by the United States.”

Within this framework, Haiti’s police must be ready and able to fight the gangs in order to achieve maximum turmoil. The U.S. government provided Haiti’s police with $312 million in weapons and training between 2010 and 2020, and with $20 million in 2021. The State Department contributed $28 million for SWAT training in July. As of 2019, there were illegal arms in Haiti worth half a million dollars, mostly from the United States.

In view of U.S. tolerance or even support of the gangs, U.S. zeal now to suppress them is a mystery. Perhaps some gangs have changed their colors, and now really do pose danger to U.S. interests.

The so-called “G-9 Family and Allies,” an alliance of armed neighborhood groups led by former policeman Jimmy Cherizier, may qualify. Not only has it emerged as the Haitian gang most capable of destabilization, but the words “Revolutionary Forces” are a new part of its name.

Cherizier observed in 2021 that, “the country has been controlled by a small group of people who decide everything …They put guns into the poor neighborhoods for us to fight with one another for their benefit.” He noted that, “We have to overturn the whole system, where 12 families have taken the nation hostage.” That system “is not good, stinks, and is corrupt.”

Referring to a mural depicting Che Guevara, Cherizier declared, “we made that mural, and we intend to make murals of other figures like … Thomas Sankara and … Fidel Castro, to depict people who have engaged in struggle.”

These are words of social revolution suggestive of the kind of political turn that repeatedly has prompted serious U.S. reaction. Beyond that, the words of Haitian journalist Jean Waltès Bien-Aimé represent for Washington officials the worst kind of nightmare.

He told People’s Dispatch that, “Activation of gangs is part of a strategy to prevent Haitian people from taking to the streets.” He scorns Ariel Henry “as a present from the US embassy,” adding that the “Haitian people do not need a leader at the moment. Haitian people need a socialist state. … We have a bourgeois state. What we need now is a people’s state.”

W.T. Whitney Jr. is a retired pediatrician and political journalist living in Maine.