It is typically believed that Russia became actively involved in Africa only in the second half of the 20th century. Of course, it is true that, for ideological reasons, the Soviet Union supported decolonization, invested significant funds in the socio-economic development of the continent, and sent military advisers and volunteers to defend the independence of the young African nations. In the 20th century, the USSR became one of the main partners of African countries.

However, the real history of Russian-African relations goes much further back than the last 50 years. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the Russian Empire was already actively involved in the affairs of the African continent – but not in the same way as other European powers, which actively took part in ‘the Scramble for Africa’ and brutally divided the continent between their colonial empires.

Resourceful diplomats and travelers promoted Russian interests in Africa, fought against the slave trade, and denounced racism long before the liberation movements of the 20th century. Bold adventurers took part in daring colonial expeditions, courageous military advisers helped Africans resist advanced European armies, and brave volunteers fought alongside the local population against the vast British Empire.

Now that Russia is making a political comeback in Africa and its influence on the continent is growing, it is particularly important to know how these relations began and developed over the centuries. Below, RT gives a historical overview of the relationship between the Russian Empire and Africa.

From the depths of the past

The first contact between Russia and Africa was established almost a thousand years ago. Nestor the Chronicler – the monk who lived at the end of the 11th century and was the first Russian historian – described settlements in Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya, and other African countries. This information was based not merely on older Roman and Byzantine texts but on up-to-date facts. Russian pilgrims regularly visited the Middle East and North Africa in those distant times, and Russian and African Christians established religious ties.

Russia’s power and influence grew around the 16th and 17th centuries, and it began providing Christian monasteries in Africa with material assistance and patronage.

Russian-African contacts were not limited to religion, however, and soon progressed into the geopolitical sphere. Russia’s first emperor, Peter the Great, wanted to strengthen Russian influence worldwide. After winning the Great Northern War against Sweden, he shifted his attention to new ventures.

At the beginning of the 18th century, the eyes of all European countries were set on India – full of unbelievable riches and resources; it was extremely promising for Europe in terms of trade. Some established trade routes with India were by land, but these passed through the Ottoman Empire, which was hostile to Russia. For Europeans, the main trade route with India was by sea, bypassing Africa via the Cape of Good Hope. However, not only was this route lengthy and full of risks, it passed through Madagascar, which pirates chose as their home base.

At the end of 1723, Peter the Great sent two frigates to Madagascar to establish control over the island. If this had worked out, Russia would have had a convenient transshipment base on the way to India and an opportunity to control Indian trade with Europe. However, a storm suddenly broke out and seriously damaged the ships. The emperor started preparing a second expedition, but he died in early 1725 before the preparations were finished. The power struggle that began after his death and the relatively long epoch of palace coups did not allow Russia to return to African affairs for some time.

This eventually happened only 50 years later. In the second half of the 18th century, during the reign of Catherine the Great, Russia established trade relations with the African territories of the Ottoman Empire – Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya – and opened a diplomatic mission in Egypt.

Comparing Russia’s activity in Africa with that of other European countries in the 18th and 19th centuries, it seems that Russians arrived too late to have a share in the colonial partition of Africa. However, this was not only a result of the geographical distance between Russia and Africa or the hostile Ottoman Empire between them. Firstly, for geographical reasons, the Russian Empire mainly developed in other directions – to the Far East and south, to Central Asia. Secondly – and far more importantly – Russians, already during that period, treated African peoples and countries quite differently than other Europeans did.

Relations between equals

It is generally believed that a multicultural environment, where different peoples and cultures can live together for long periods, is ideal for fighting stereotypes and eliminating bias, racism, and other shocking delusions of the past. The Russians, whose empire was built on principles of equality and mutual respect with the various peoples that inhabited their lands, naturally possessed these qualities. This is clearly demonstrated by the example of the Russian officer and engineer, Egor Kovalevsky, who lived in the first half of the 19th century.

In 1847, he was invited by Muhammad Ali Pasha to Egypt to search for gold deposits. However, this was not the only part of Kovalevsky’s job. The second, secret part of his mission was to collect information that could serve Russian interests. This included information on projects for constructing the Suez Canal and the dam across the Nile, and studying trade in Ethiopia and Arabia. During his work in Africa, Kovalevsky became one of the first European researchers to compile a detailed map of so-called ‘Inner Africa.’ Kovalevsky and members of his expedition traveled all the way to present-day South Sudan. Along with his partner, biologist Lev Tsenkovsky, he also collected important geological, biological, and zoological specimens in Africa.

In his diaries, Kovalevsky expressed indignation about the slave trade, which was still widespread in Africa, and the racism demonstrated by Arab slave traders.

His anger was shared by Nikolay Gumilev – a renowned Russian poet, traveler, and hero of the First World War. Having organized two expeditions to Africa in 1909 and 1913, Gumilev studied African peoples’ customs and way of life, provided the locals with medical aid, and bought enslaved people’s freedom at his own expense.

Russian travelers and officers generally considered the derogatory attitude towards Africans wild and revolting. They took a firm stance on the issue without attempting to interfere in the internal affairs of other nations. Meanwhile, for the locals, the behavior of Gumilev and Kovalevsky strongly contrasted with the actions of other Europeans in Africa.

Cossack adventures

Most people have never heard about the village of Sagallo, situated on the Gulf of Tadjoura in modern-day Djibouti. However, this is where the first Russian settlement in Africa appeared in 1889, founded by Nikolay Ashinov. This adventurer had visited the African continent several times before and saw tremendous opportunities there.

Returning to Russia, Ashinov managed to obtain the support of influential conservatives – publisher Mikhail Katkov and Chief Prosecutor of the Holy Synod Konstantin Pobedonostsev – who supported his initiative to establish an Orthodox Christian mission in Abyssinia (the name of Ethiopia at the time). Merchants from Nizhny Novgorod interested in promoting Russian interests in this region also provided Ashinov with financial support.

Gathering 150 people, including monks and Terek Cossacks, Ashinov departed for Africa at the end of 1888. On January 6, 1889, the Russian colonists arrived in present-day Djibouti. They occupied the empty Sagallo Fort and founded a settlement on its territory called New Moscow. Right away, the colonists started working the land, planting grapes, cherries, lemons, oranges, cultivating vegetable gardens, and even discovering salt, iron, and coal deposits.

Interestingly, the local Afar people took a liking to the Russian colonists. The Sultan of Tadjoura gave Ashinov official permission to build the settlement, and the Cossacks taught Africans new farming techniques. However, this idyll did not last long.

The territory the Russian colony was founded on was formally under the French protectorate. The French saw Ashinov’s settlement as an encroachment on their rights and, in February 1889, sent a squadron consisting of one cruiser and three gunboats to Sagallo. The commander of the French forces presented an ultimatum to the Russians, but none of them spoke French, so they did not understand a thing.

The French squadron opened fire at the colony and killed six settlers, only one of whom was a ‘terrible Cossack,’ the rest were women and children. The surviving Russians, who possessed only guns against the warships, capitulated and were sent back to Russia. Meanwhile, the French destroyed everything that the Russian colonists had built.

While Europeans at the time, including some Russians, condemned Ashinov’s expedition and called the Cossack leader a scammer and a fraudster, this is an unfair assessment. Firstly, Ashinov published the first Russian-Abyssinian alphabet, which hardly fits the image of a rogue and scammer. Secondly, the mission of 1889 was aimed at developing trade, economic, and cultural ties between Russia and the local population. The locals and the Sultan of Tadjoura cordially received the Russian settlers, who clearly had more rights to these lands than the French colonizers. Nevertheless, the first Russian settlement in Africa came to naught. Soon, the Russians returned to East Africa again, but this time to protect the locals from Western European invaders.

Standing guard over Ethiopia

By the end of the 19th century, most of Africa had been divided among the great European powers, but Ethiopia remained one of the few independent African countries. This was facilitated by Ethiopia’s geographical remoteness from the coast, its rather large size, and the remnants of former power, which made it a formidable opponent for enemies. Moreover, since Ethiopians are Christians, other Christian nations considered it wrong to colonize the country.

However, Italy – which united only in 1871 and was too late to have a share in the ‘Scramble for Africa’ – decided to seize Ethiopia anyway. First, it captured small coastal areas on the territory of modern Eritrea, where the power of the Ethiopian Negus (emperor) was weaker. Unable to gain victory over the Italians, Ethiopia initially made certain concessions to the colonizers. However, when Rome directly demanded the establishment of a protectorate, the Ethiopians broke off all ties with Italy. War was in the air, but Ethiopia had a great northern friend – Russia.

Parallel to Ashinov’s rather adventurous expedition, the Russian Empire also operated in Ethiopia at the level of military intelligence. In 1887, 20-year-old Second Lieutenant Viktor Mashkov submitted an analytical note to Minister of War Pyotr Vannovsky on Ethiopia’s military and political situation, and pointed out the need for Russia to build relations with this African country.

The following year, having received the personal approval of Emperor Alexander III, the young officer Mashkov joined the reserve and went to Africa under the guise of an independent correspondent. He managed to obtain the support of Emperor Menelik II and establish the first Russian-Ethiopian contacts. An active correspondence ensued between Menelik II and Alexander III, and work began at the diplomatic level. Linked by a common religion and having common geopolitical interests, the two countries quickly built constructive and friendly relations.

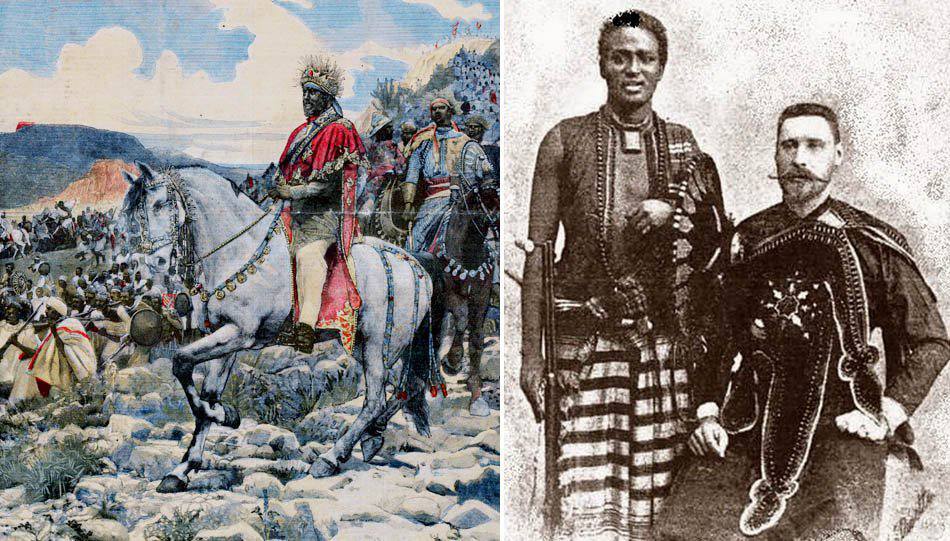

In 1895, when the First Italo-Ethiopian War began, Nikolay Leontiev’s formidable figure watched over the Africans. At the age of 33, Leontiev was only a yesaul (captain) of the Kuban Cossack army. Still, factually, he was the commander of a group of military advisers and the right hand of Emperor Menelik II.

In addition to teaching the Ethiopians European military strategy and tactics, Leontiev brought 30,000 rifles, 40 mountain guns, and millions of cartridges and munitions from Russia. Russian military advisers established strict discipline and taught Ethiopian fighters modern methods of warfare. The results of this training were quickly demonstrated.

The Battle of Adwa on the 1st of March 1896 shocked not only the Italians but even the Russians and the Ethiopians, who did not expect such success. The Italian expeditionary corps was almost completely destroyed – out of 15,000 people, 11,000 were killed or injured, and 3,500 surrendered. The Ethiopians themselves lost about 4,000 people.

Forced to recognize the independence of Ethiopia, in 1896, Italy became the first European country to admit defeat in a war with an African country and agreed to the payment of indemnities. Russia helped Ethiopia defend its independence and later helped form its regular army. Importantly, this cooperation was based on principles of equality and mutual respect.

In addition to Mashkov and Leontiev, other outstanding Russian officers and researchers participated in the Ethiopian campaign. For example, Aleksandr Bulatovich, the first European to explore the Kingdom of Kaffa, and Evgeny Maksimov, a hero of the Russo-Turkish War who explored Central Asia, was a journalist in Ethiopia and participated in another war where Russia helped Africa fight against Western colonizers.

Russians and Boers are brothers forever

In 1652, the first Dutch settlers arrived at the Cape of Good Hope and began exploring the southern part of Africa. They founded the Cape Colony and its capital, Cape Town. In 1795, amid the French Revolutionary Wars, Great Britain took advantage of the fact that the French were occupying the Netherlands and captured the Cape Colony. The descendants of the Dutch colonists – the Boers – strongly opposed the mass relocation of British colonists, the introduction of English as the official language, and increased taxes.

The Boers moved to the northeastern region of modern South Africa, where they founded two republics: Transvaal and the Orange Free State. For a while, the life of the Boers returned to normal, but things changed when vast reserves of gold and diamonds were found on their territory. In 1880-1881, Britain’s first attempt to capture the Boer republics failed, but the British did not abandon their plans and prepared for a new conflict. Realizing that war was inevitable, the Boers launched an attack of their own in 1899. The Second Boer War began.

Officially, all other countries remained neutral, but public opinion and the governments of many European nations sided with the Boers. Some people, like the Dutch, supported the Boers because of ethnic proximity. However, most countries were inspired by the struggle of the small free Boer republics against the vast British Empire. The French, Germans, Irish, and Russians all supported the Boers, hoping to defeat the British hegemony in this remote corner of the world.

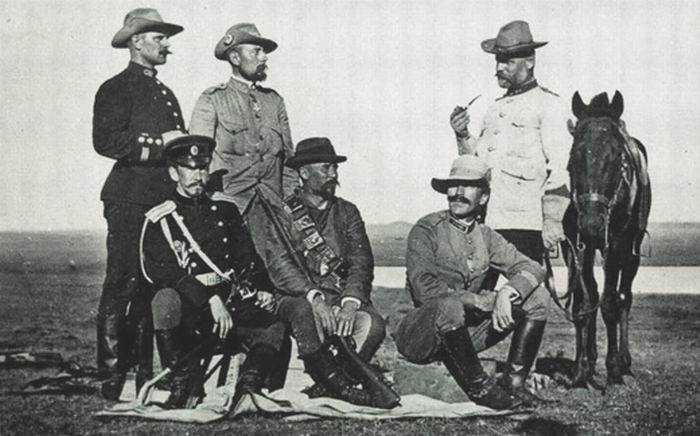

The Boers received assistance in the form of volunteers, money, and equipment from all over the world. It may seem that despite the general support for the Boers in Europe, the number of volunteers was not that big – less than 3,000 people. However, there are several essential things to remember in this regard. Firstly, at the beginning of the conflict, there were no more than 28,000 British soldiers in South Africa, while the Boers had about 45,000 people fighting on their side. So initially, volunteers comprised a significant percentage of those who supported the Boers, and their ratio was greater than those who sided with the British.

Secondly – and this was particularly important – the volunteers were not ordinary people but mostly officers with prior combat experience. Only around 200 Russian volunteers came to fight alongside the Boers during the three years of the war, but these were some of Russia’s best men. The above-mentioned hero of the Ethiopian campaign, Yevgeny Maksimov, became the second commander of the Boer foreign volunteers. Aleksey Vandam, also a young officer, later came to prove himself not only as a general staff officer and a hero of the First World War but also as an outstanding Russian geopolitician and geostrategist. The future chairman of the State Duma, Alexander Guchkov, one of the first Russian aviators, Nikolay Popov, and many other renowned people of their time also fought on the side of the Boers.

The life of foreign volunteers in Africa was not easy by any means. They were not paid since the rural Boer republics had little money to give. Officer positions were distributed selectively, and without knowing Dutch and having authority among the locals, a foreigner – even a titled nobleman or an outstanding military man – could only count on a low rank. Added to this were the Boers’ natural pride and unwillingness to obey anyone’s orders, the demanding service conditions, the hot climate, and all the hardships of guerrilla warfare.

Initially, the Boers treated all volunteers cautiously, but the Russians quickly gained authority and favor in their eyes. According to numerous accounts, all the volunteers who came to South Africa were ideologically motivated to help the Boers in their struggle for freedom. Russian volunteers did not steal or engage in looting; they served honestly and fought bravely on par with the Boers. For example, despite being shot in the head, Yevgeny Maximov returned to the ranks soon after recovery, continued reconnaissance missions, and led troops into attack.

In addition to directly participating in the fighting, Russian volunteers also provided medical aid to the Boers. One detachment of the Russian Red Cross, which arrived at the beginning of the war and numbered only 33 people, assisted almost 7,000 sick and wounded people in just the first six months of fighting.

Eventually, the fight between David and Goliath ended with the latter’s victory. Employing concentration camps for the first time in history and introducing a brutal occupation regime, the British Empire finally managed to break the resistance of the Boers. In 1902, the war ended, and Britain annexed the Boer republics.

Despite the unsuccessful outcome of the war, Russian volunteers did everything in their power to help the Boers. Moreover, Russia’s support became crucial for preserving the independence of other African countries, including Ethiopia. In those distant times, Russia laid the foundation and general principles on which it continued building its policy toward African countries in the 20th and 21st centuries.