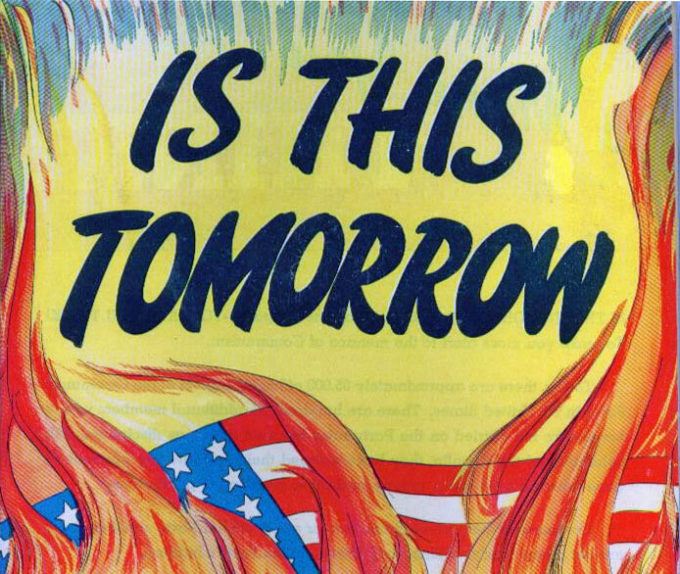

Washington is talking itself into war again. The signs are unmistakable.

Admirals are warning of China’s preparations to invade Taiwan and defense hawks on the Hill point to Taiwan as simply the first step in China’s long-term strategic bid for global military hegemony. Nervous European allies see a Russian troop concentration in Eastern Ukraine as evidence for an impending Russian invasion and the Biden administration responds by saying that America’s support for Ukraine is “ironclad.”

When U.S. politicians and senior military leaders invoke the threat of war, Americans must treat their comments seriously. With this in mind, it’s important to understand what did and what did not happen 80 years ago.

From 1920 until the outbreak of war with Imperial Japan, the Navy’s Pacific Fleet practiced fighting the Imperial Japanese Navy on an annual basis. These exercises informed extensive, detailed war plans that were developed in the 1930s.

Normally, after concluding the exercises, the fleet returned to its bases on the West Coast. In 1940, however, the fleet was ordered to remain at Pearl Harbor. Admiral James Richardson, commander-in-chief, U.S. Fleet, regarded the decision with grave concern.

Admiral Harold Stark, chief of naval operations, explained the decision to his subordinate commanders in a letter dated May 27, 1940, in which he said, “You are there because of the deterrent effect which it is thought your presence may have on the Japs going into the East Indies.”

On June 17, 1940, Marshall convened a meeting with Army planners to specifically examine the worst-case scenario: a Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Marshall knew the Philippines could not be defended for long without reinforcement against a determined Japanese attack. If the fleet were destroyed in Pearl Harbor, an operation to relieve the beleaguered American garrison in the Philippines would be impossible. As they often do, policy decisions in Washington outpaced U.S. military preparations.

On July 26, 1941 FDR issued an executive order freezing Japanese assets in the U.S. and halting all trade with Japan. Army and Navy strategic planners understood Japan’s strategic dilemma: Either Tokyo meets FDR’s conditions for lifting the oil embargo—the complete evacuation of Japanese forces from China—or Tokyo secures oil, rubber and other critical war materials by striking south to conquer the resource-rich Dutch East Indies.

Retaining the fleet in Hawaii did nothing to deter Japan. The war plans developed in the 1930s were shelved. Neither the U.S. armed forces nor the resources to implement the plans existed in December 1941.

After Pearl Harbor, 30,000 U.S. Soldiers tasked to relieve the American garrison in the Philippines were diverted to Australia. The U.S. Navy could fight its way across 8,000 miles of ocean and deliver them safely. The humiliating surrender of American forces on Corregidor followed in May 1942.

Is now the time for President Biden to take inflexible policy positions on Eastern Ukraine or Taiwan from which it is extremely difficult to retreat? Resorting to the use of military power against continental opponents like China or Russia—nations that fight in their own “near abroad”—demands the persistent employment of powerful U.S. and allied ground, air, and naval forces. America’s armed forces today are no more ready for this mission than were our forces in December 1941.

Moreover, the great powers that once stood between Washington and its opponents in 1941 no longer exist. With few exceptions, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is a collection of U.S. military protectorates that bring modest capability to a U.S.-led fight. Germany is an economic superpower, but a military pygmy.

To date, only Japan has rebuilt a fraction of its former military power, but the notion that Japan would join the U.S. in a war against China or Russia is fanciful. In nearly all but Washington’s eyes, China is not Imperial Japan and Russia is not the Soviet Union. If anything, everyone in Asia wants to do business with China, not fight a destructive regional war.

For the moment, Washington and its NATO allies are discovering that the most dangerous threat is not a handful of Russian soldiers in green uniforms without insignias, nor is it a coordinated cyber-attack: It is a high-end conventional offensive launched by Russian ground forces from Russian soil that could prove impossible to halt.

Will Moscow’s patience with Ukrainian attacks on Russian-held territory in the Donbass finally end? The answer is unclear.

It is known that all of the nuclear armed submarines in Russia’s Pacific fleet recently put to sea on high alert. Moscow’s move does not indicate a readiness to employ nuclear weapons. Rather, the action is a signal to Washington that if U.S. and allied forces should falter in a future collision with Russian forces in the Black Sea or Eastern Ukraine, Moscow possesses a secure second-strike nuclear weapons capability that the U.S. armed forces cannot defeat.

Pearl Harbor is a grim reminder that threats without the ability to carry them out do not constitute deterrence. The thought is certainly worthy of President Biden’s consideration.

*

Douglas Macgregor, Col. (ret.) is a senior fellow with The American Conservative, the former advisor to the Secretary of Defense in the Trump administration, a decorated combat veteran, and the author of five books.

The original source of this article is The American Conservative