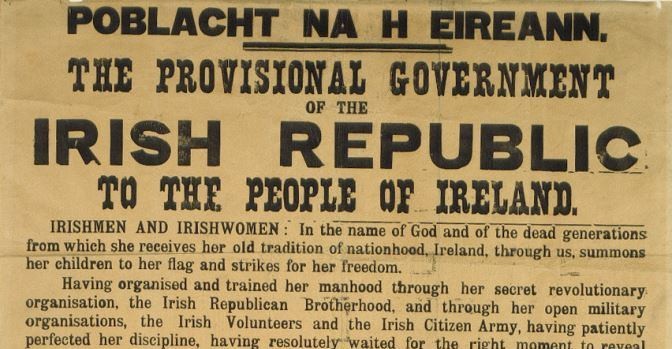

First published on March 30 2016 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 1916 Irish Uprising.

Text and analysis by renowned Irish artist Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin

This Easter we commemorate the 107th anniversary of the heroic Easter uprising of 1916.

It has been one hundred and seven years since the heroic Easter uprising of the IRB (Irish Republican Brotherhood) and the ICA (Irish Citizen Army) against the might of the British Empire in 1916.

The planning of the 2016 commemoration was thrust into the hands of the conservative Fine Gael/Labour government who would have been at least a bit uneasy about the potential for increasing the political support base for the more politically radical Sinn Féin. However, the problem of artistic representation of the events was at least partially resolved by the well-worn techniques used by successive conservative Irish governments over the years since the Easter Rising: mythologisation, diversion and counternarrative.

The fact that there is still no major monument representing the leaders of the 1916 rebellion in a realist or social realist style (unlike the sculptures of the constitutional nationalists Parnell and O’Connell that top and tail O’Connell St in the centre of Dublin city) is not just indicative of the passing of time and the change in artistic trends.

Social realism as an international movement arose out of a concern for the working class and the poor, and criticism of the social structures that kept them there. As an artistic style, social realism rejected conservative academic convention and the individualism and emotion of Romanticism. It became the chosen style of artists, writers, photographers, filmmakers and composers who wished to document and highlight the harsh realities of contemporary life.

In the context of 1916, artistic representation presented a political dilemma for elites. How do you portray events that essentially forged current political independence yet potentially could also destroy that power if the masses decided to bring its ideals to full fruition? The answer was to proceed tactically. Mythologisation allows for representation to be distanced from the actual events, diversion focuses attention on less important aspects of the events and counternarrative sets up alternative, less threatening or even completely oppositional views of the same events.

Mythologisation

It took until 1935 before a public monument to 1916 was unveiled. A bronze statue, The Death of Cuchulain, was at the centre of a public event which included a military parade, bands playing and trumpets from the rooftops. According toSighle Bhreathnach-Lynch in History Ireland:

Christian ideals, legend and revolutionary nationalism come together in the best known and most artistic of all 1916 monuments, the statue of Cu Chulainn [sculptor Oliver Shepherd] in the General Post Office, Dublin, headquarters of the Rising. It depicts the legendary hero of ancient Ireland bravely meeting death, having tied himself to a stone pillar to fight his foes to the last. Although originally modelled as an exhibition piece in 1914, before the Rising had taken place, it was subsequently deemed to be the most suitable symbol of the event partly because the Cú Chulainn legend was perceived by Patrick Pearse as embodying ‘a true type of Gaelic nationality, full as it is of youthful life and vigour and hope’. The religious feeling invoked by its similarity to the Pieta theme in the pose of the figure also coincided with Pearse’s own ideology which fused Christian ideals with revolutionary nationalism.

The linking of ‘Christian ideals with revolutionary nationalism’ was also apparent in the design of the Garden of Remembrance at the former Rotunda Gardens in Parnell Square, a Georgian square at the northern end of O’Connell Street. The Garden of Remembrance was opened in 1966 on the fiftieth anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising by the then President Éamon de Valera. The garden ‘is in the form of a sunken cruciform water-feature. Its focal point is a statue of the Children of Lir by Oisín Kelly, symbolising rebirth and resurrection, added in 1971.’ According to the myth, The Children of Lir were turned into swans by their jealous stepmother:

As swans, the children had to spend 300 years on Lough Derravaragh (a lake near their father’s castle), 300 years in the Sea of Moyle, and 300 years on the waters of Irrus Domnann Erris near to Inishglora Island (Inis Gluaire). To end the spell, they would have to be blessed by a monk. While the children were swans, Saint Patrick converted Ireland to Christianity.

It is interesting to note that the original design was to include ‘busts of prominent patriots in niches’ but while the proposal was approved ‘the project was deferred’ [p. 158].

The connection with Christian ideals also acted as anantidote to any left wing or secularist tendencies in the political movement which had long strived to avoid sectarian divisions:

For the IRB, Irish nationality had nothing to do with religion and nationality superseded all sectarian divisions. The question was Ireland against England, not Catholic against Protestant. It was defined not by blood or faith, but by commitment to this world view. In fact, several of the most prominent republicans of the early 20th century – notably Bulmer Hobson and Ernest Blythe, were Ulster Protestants.

This is particularly true of the ICA (Irish Citizen Army) which was set up in Dublin for the defence of worker’s demonstrations from the police. Seán O’Casey, the dramatist and socialist, was a member and wrote its constitution, ‘stating the Army’s principles as follows: “the ownership of Ireland, moral and material, is vested of right in the people of Ireland” and to “sink all difference of birth, property and creed under the common name of the Irish people”.’

The Christian emphasis has also been shown in the choice of Easter in March (a moveable feast) for the days of the 2016 commemoration rather than on 24–29 April, the actual dates for the Rising in 1916.

Diversion

Moving from sculpture to filmmaking, RTÉ (the national broadcaster) showed a five-part 1916 commemorative drama, Rebellion, set during the days surrounding the Easter Rising. There was much criticism of the minor roles played by the leaders of the Rising with the main emphasis on fictional characters instead. As one commentator noted:

Colin Teevan [the writer] made the ambitious choice to have the fictional characters as the main dramatic drivers, while the Rising’s familiar protagonists operate on the sidelines. […] Brian McCardie, with the Edinburgh burr of James Connolly, makes one dramatic entrance; Countess Markievicz (Camille O’Sullivan) gets just a single, hammy scene.

Another commentator wrote:

1: Key Characters Were Not Brought Convincingly To Life. One of the pivotal scenes in the final episode was the execution by firing squad of James Connolly. Yet the socialist leader had been thinly-sketched and viewers will have greeted his death with a shrug. We never really knew him – why did we care that he was gone? And did RTE have to slap a Six Nation countdown in the corner as he was sent to his maker? Historians will also surely quibble with the portrayal of De Valera as fascist sociopath.

Éamon Ó Cúiv (a Fianna Fáil member of parliament) described the portrayal of his grandfather Éamonn De Valera, one of the leaders, as an “embarrassment”:

There is no basis at all for the representation of Éamonn de Valera or of the common perception of him at the time on the programme Rebellion. It was entirely made up and it’s an embarrassment to RTÉ to spend public money – and they spent a lot of it – on this type of programme and not give a truthful portrayal of real, historical people – including Markievicz, Pearse and de Valera.

Counternarrative

Most controversial of all in this centenary commemoration was the choice of Henry Grattan, Daniel O’Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell and John Redmond for four large portrait banners which Dublin City Council hung to the front of the Bank of Ireland on College Green for the duration of the Easter Rising commemoration period. While three of these constitutional nationalists come from different times, John Redmond had encouraged thousands of Irishmen to join the British Army and fight in the Great War. He ‘lateracknowledged that the Rising was a shattering blow to his lifelong policy of constitutional action. It equally helped fuel republican sentiment, particularly when General Maxwell executed the leaders of the Rising, treating them as traitors in wartime.’

The presence of Redmond on such a prominent banner drew the ire of an activist group called Misneach who stated that they ‘drew over Redmond’s face last night in a protest against “revisionist propaganda”. The group said it painted the figure 35,000 on the banner to represent the number of Irish people estimated to have died during World War I.’

Changing times

Such actions against the counternarrative and the popularity of the commemorations show that the consciousness of the 1916 ideals are alive and well in the general populace. A similar consciousness among cultural creators in Ireland, dealing directly with the many social, economic and political problems in Ireland today will go a long way towards reaching those ideals.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist who has exhibited widely around Ireland. His work consists of paintings based on cityscapes of Dublin, Irish history and geopolitical themes (http://gaelart.net/). His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country at http://gaelart.blogspot.ie/

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG)