Walter Teague, the encyclopedic and strong-willed giant of the anti-war movement who passed away on March 27 from heart failure at the age of 86, was a stickler for detail. In the postscript of the final email he sent me in February—the culmination of a dozen hours of interviews I’d done with him in recent months for my upcoming book on the radical left—he called me out for having used an abbreviated form of the organization he founded in late 1964. “P.S.,” he typed, through the arthritic pain that had all but consumed the use of his right hand by the end, “the official name was U.S. Committee to Aid the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. Each element chosen for special reasons.” Precise to the end.

That precision was honed as an office clerk in the Air Force in post-war Japan. Teague had hoped to go to college but couldn’t afford it, a strange circumstance for the grandson of one of the most successful industrial designers of the mid 20th century to find himself in. Kept at a cold arm’s length by his father his entire childhood, Teague was left to make his own way in the world. Arriving in Okinawa in 1957, it didn’t take him long to realize that the life of a one-stripe Airman—barracks, mess halls and bugle calls—was not for him. He figured out that if he brought his wife over, however, his superiors would have no choice but to let him live off-base. Using nothing but construction tips from the Encyclopedia Britannica and dribs and drabs of his wife’s secretarial salary back in New York, Teague built his own typhoon-proof house, complete with a water collection system on the roof and room to park his rusty Ford convertible in the living room. Having his wife at hand came with another benefit: Leveraging her civilian status, he was soon frequenting the officers club as her guest.

Being part of an occupying, albeit friendly, force, Teague began to think about politics for the first time, noticing not only the racial and class divisions within his company but also the arrogance and imperialism of his country. His innate skepticism, which got him booted from Sunday school at age 7 for contradicting his teacher’s account of where babies come from, was stoked. “The main thing my time in the Air Force taught me was that the United States was an empire and it was lying through its teeth to everybody,” he told me.

By 1963, Teague was back in New York with two young sons and a failing marriage. Leaving his family in Brooklyn, Teague moved into a rent-controlled apartment on MacDougal Street that he inherited from his filmmaker brother and worked as a salesman for IBM. He was reading a lot and started to attend political gatherings. One night, he gave an older woman a ride home from a Fair Play for Cuba meeting and she thanked him by dropping a pile of old National Guardian issues in his lap. The Leftist paper of record was a revelation for him, but he didn’t feel that any of the existing political groups or parties was quite the right fit. And then the war started.

“What I saw in the peace movement in 1964 was that many good people were afraid to be identified with the Vietnamese too much,” he said. “And [I realized that] if you play into the fact that you can’t talk about them, that’s sort of like saying, well maybe they are gooks stabbing our boys in the back. So, I decided that what the peace movement needed was a group that supported the Vietnamese.” Thus was born the most awkwardly named political group in the history of, well, just about all political groups: The U.S. Committee to Aid the Liberation of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam.

Teague devoted the next ten years of his life to humanizing the Vietnamese people and bringing an end to America’s war against them. In addition to popularizing the use of the Viet Cong flag in antiwar marches, Teague created the biggest repository of Vietnamese literature and film this side of the Atlantic at his Chelsea loft and spent countless evenings screening movies and hawking pamphlets at the Free School and on the streets of Greenwich Village. And he enjoyed the challenge of debating passers-by even if it elicited some angry retorts. “It’s amazing,” he told the Guardian in December 1965, “but so far nobody’s been hurt.”

While Teague was fearless in his pursuit of empathy and justice for the Vietnamese, he wasn’t careless. Far from it: he always minimized risk, looking for ways to go right up to the edge of the law without crossing it (though he still managed to get arrested dozens of times). That’s why he refused to join fellow veteran Robin Palmer in stenciling Viet Cong flags on the side of mailboxes, turned down overtures from would-be bombers and outfitted his loft on West 22nd Street with a metal door and safe room. It’s also how he was able to defy HUAC’s attempts to make him testify and to come up with the idea of replacing wooden rods with cardboard tubes from the garment district so that the cops couldn’t stop him and his fellow protesters from marching with his beloved Viet Cong flag.

Teague was at most of the tent-pole events of the Sixties, leading the Revolutionary Contingent over the bridge to the Pentagon, constructing a 40-foot-tall tower out of cardboard tubes to fly Viet Cong flags at the first MOBE march in Central Park, and working the printing press in Movement City at Woodstock. He did miss attending the Democratic National Convention though, opting instead to accept an invitation to give a speech to a peace group in Japan.

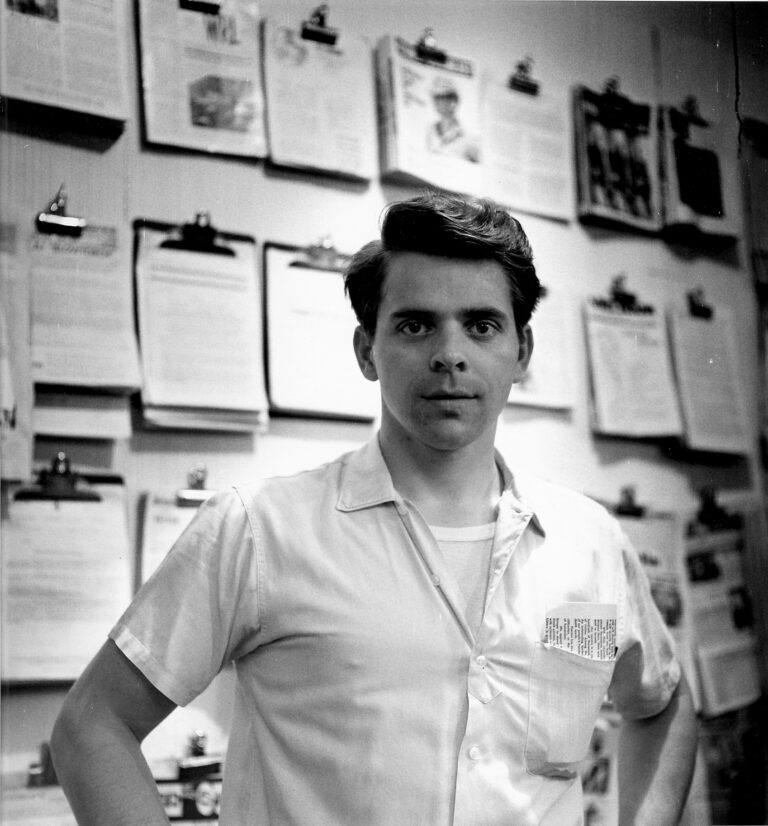

With his boyish good looks, patrician voice and short hair, he was hard to dismiss (or, for those with two x chromosomes, hard to miss), even when he was taking the most radical of positions. “Very charismatic, articulate as hell,” is how Brent Sharman, who worked side-by-side with Teague in the early 70s at the Washington Square Methodist Church, described him. “He was a strong man, a hard worker and exuded energy and discipline.” Teague wasn’t good at everything though. “Teague couldn’t dance for shit,” Sharman recalls. When someone pointed that out to him, Teague responded, “Well, I’m not going to dance until the war is over.”

When the war finally ended in 1975, though, he didn’t feel much like dancing: that same year his eldest son was killed in a car accident at the age of 16. Soon after, Teague moved to Washington D.C, where he became a therapist and ended up marrying the love of his life, a Cambodian woman who’d survived five years in the Pol Pot’s killing fields, Soc Sinan. The house they bought in 1987 and lived in together until Sinan died of Hepatitis in 2010 was as much an archive as a home. The entire ground floor was piled high with binders, boxes and clip boards full of correspondences, political pamphlets, photographs and surveillance files—a collection that became increasingly difficult to manage in the later years of Teague’s life.

Walter knew he was dying and, not believing in God or an afterlife, was unsentimental about nature running its course. Given his intellect and his work ethic, the physical limitations he faced and the crimp they put into his plans to write an autobiography were no doubt frustrating, but he was rather matter of fact about it and in the end I think he felt like he’d had a good run. Neither a pacifist nor a strict revolutionary, Walter Dorwin Teague III was a realist with a critical, exacting mind who sought to convince the world around him of what seemed obvious and just.

One of the last anecdotes Walter related to me took place at a protest put on by a Yippie splinter group called the Crazies. When two of the group’s leaders stripped naked and ran down the aisle to deliver a raw pig’s head to whichever Liberal politician was on the dais that day, an older woman began whacking one of them with her umbrella. Walter leapt up and, without the need of amplification, bellowed, “Some of you people are more upset by nakedness than by napalm!” At that point, a large group of nuns started applauding. Walter had pinpointed the hypocrisy in the room and called it out. A good day at the office.