Academics Benny Morris of Ben-Gurion University and Benjamin Z. Kedar of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem have produced an extraordinary paper based on a welter of archival material, exposing in disturbing detail the hitherto obfuscated dimensions of an operation by Zionist forces to use chemical and biological weapons against both invading Arab armies and local civilians during the 1948 war.

That brutal conflict created the state of Israel, and led to permanent displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, known as the “Nakba” – Arabic for disaster, catastrophe, or cataclysm.

Morris and Kedar offer a highly granular timeline of events, starting in the initial months of that year, as Britain prepared to evacuate Mandatory Palestine on May 15. In the lead up to that date, Zionist settlers were very much on the defensive, with militias “continuously” attacking their enclaves and convoys, with the support of neighboring armies, due to their joint rejection of UN Resolution 181, passed in November 1947, which proposed partitioning Palestine into separate Arab and Jewish states.

With Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Transjordan all having expressed an intention to invade Palestine when Britain left – and having been actively encouraged in this regard by British intelligence – Zionist guerrillas began mounting an offensive, not merely to neutralize Arab fighters, but capture territory, destroying houses and civilian infrastructure along the way, to prevent displaced residents from returning.

In order to augment the latter component of this effort, ensure Zionist seizure of Arab villages and towns was permanent, facilitate easier conquest of further areas, and hinder the progress of advancing Arab armies, these militias began poisoning wells with bacteria to create local epidemics of typhoid, dysentery, malaria and other diseases, in direct violation of the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which strictly prohibits “the use of bacteriological methods of warfare.”

As we shall see, the Zionists were suitably emboldened by the clandestine operation’s success that they eventually attempted to expand their poisoning campaign to invading Arab armies’ home soil.

“State of extreme distress”

The code name of the biological warfare operation, “Cast Thy Bread” was a reference to Ecclesiastes 11:1, which directs Jews to “cast thy bread upon the waters, for after many days you will find it again.”

The prospect of using biological weapons against the “enemy” had been percolating among the Zionist movement for some time, come the 1948 war. Three years earlier, immediately after the end of the war in Europe, Crimea-born Jewish partisan leader and poet Abba Kovner had, after reaching Palestine, hatched a plot to mass-poison Nazis, to avenge the Holocaust.

Kovner intended to either infect waterworks in German cities, or poison thousands of SS officers detained in Allied prisoner of war camps with a fatal disease. Having procured poison from two academics at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, he travelled to Europe to enact the plans, but was arrested by British security officials en-route, right after dumping his deadly cargo in the sea, and aborting his mission.

The former strategy resurfaced in Zionist consciousness as the prospect of a war of independence loomed, and became formalized with the creation of HEMED by Haganah, the primary Jewish paramilitary organization in Mandatory Palestine 1920 – 1948. HEMED’s three components – titled A to C – dealt with chemical and biological defense and warfare, and nuclear research.

On April 1, 1948, David Ben-Gurion, a leading figure in the Zionist movement who is regarded as the primary founder of the state of Israel, and served as its first Prime Minister, met with a senior representative of Haganah to “discuss the development of science and speeding up its application in warfare.”

Two weeks later, bacteria that would induce typhoid and dysentery among those who consumed it was distributed to Haganah operatives across Palestine. Before war even broke out on May 15, it had been used to poison water sources in Arab-held areas, the West Bank city of Jericho being the first documented instance. This was done in order to “undermine Palestinian staying power in still inhabited sites and to sow hindrances along the prospective routes of advance of invading Arab armies.”

That Zionist militants did not expect areas earmarked for Palestinians under the UN’s partition plan to remain Arab-inhabited in the event of victory in the looming war is strongly underlined by their targeting of many of these villages and towns in advance.

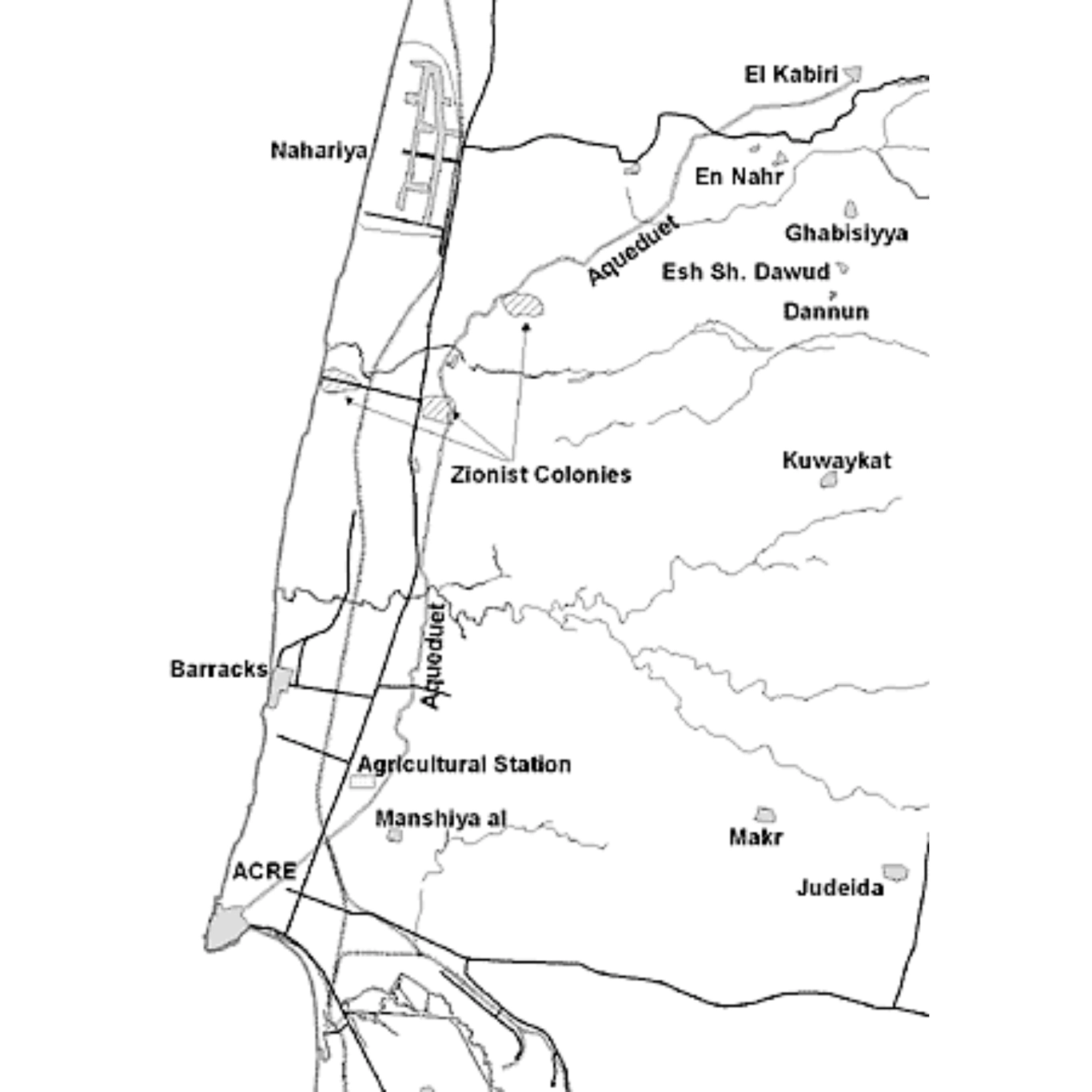

A vital aqueduct in Kabri that was the primary if not sole source of water for many nearby Palestinian settlements was poisoned on May 15. The paper’s authors call it “the most serious and potent use” of biological weapons during the entire 1948 War.

The historic northern city of Acre, designated part of a future Arab state by the UN, was one of the areas dependent on the aqueduct for water. The morale of its inhabitants is said by Morris and Kedar to have been “already shaky” at this juncture, due to Haganah’s recent conquest of the Arab parts of nearby Haifa, the region’s capital, and resultant flight of most of its population, many of whom took up residence in Acre.

Haifa’s capture by Zionists – achieved despite protection from British forces – cut off Acre not only from Haifa but neighboring Lebanon, and the prospect of Britain’s departure contributed to “plummeting” spirits among the population. The outbreak of a typhus epidemic, courtesy of Operation Cast Thy Bread, left Acre “in a state of extreme distress,” the city’s mayor reported on May 3. No one had the slightest clue that it had been deliberately created, for precisely this reason.

‘What was the point?’

Morris and Kedar assert that despite the widespread campaign of biological warfare engaged in by Zionist militias across Palestine, there were comparatively few reported casualties as a result – although dozens of Palestinians, and some British soldiers, are confirmed to have been killed – and the progress of invading Arab armies was barely halted due to disease outbreaks among soldiers.

“The apparent ineffectiveness…and problems in producing and transporting the weaponised bacteria may well have curbed enthusiasm for the campaign among Israeli defence executives. What was the point?” the pair speculates.

Such conjecture is somewhat bizarre, given so many of their findings, and private communications between Haganah operatives cited elsewhere in the paper, make abundantly clear the strategy was highly valued, and proved pivotal in the permanent capture of many Arab villages, towns, and cities.

Take for instance the aforementioned Acre. One day into the war, Zionist forces attacked the city, and delivered an ultimatum: unless inhabitants capitulated, “we will destroy you to the last man and utterly.” The next night, local notables duly signed an instrument of surrender, and three-quarters of the Arab population – 13,510 out of 17,395 – were displaced in a proverbial pen stroke.

Accordingly, the academics refer to a previously unpublished June 1948 report from Hanagah intelligence unit Shai, which attributed the speed and ease with which Acre fell into Zionist hands in part to the epidemic they had earlier unleashed. The city was far from unique in this regard – outbreaks of typhus, and “panic induced by rumours of the spread of the disease” was determined to be “an exacerbating factor in the evacuation” of several areas.

Hindsight can on occasion mislead, but it was not retrospective pattern recognition that led Zionist militants to eagerly expand the poisoning campaign as the war unfolded. Between June and August 1948, two pseudonymous Hanagah operatives exchanged a series of cables while the bitter battle for Jerusalem raged. One became increasingly angry at the lack of progress, imploring the other, “immediately stop your neglect of Jerusalem and take care to send Bread here [emphasis added].”

Then, on September 26, “an important Zionist executive” proposed to Ben-Gurion a wide-ranging blitz of “harassment by all means,” not only in target areas of Palestine, but also belligerent Arab countries. This counter-offensive was intended to reverse the Egyptian Army’s capture of UN-mandated Jewish territory, seize some or even all the West Bank for settlement, and prevent the return of displaced Palestinian to areas partially or wholly in Zionist control.

The utility of biological warfare in achieving those objectives was obvious, and cables initiating the literally toxic process were fired off from the highest levels of Hanagah to its assorted militias the same day. Cairo’s water supplies were a major stated destination. Plans to that effect were evidently being explored in advance elsewhere as well.

On September 21, a Hanagah operative hiding in Beirut reported to headquarters on possible targets for sabotage operations in Lebanon, including “bridges, railway tracks, water and electricity sources.”

Lebanon remained in the crosshairs for some time, even as the war neared its completion, and Zionist victory was all but assured. In January 1949, two months before the country and Israel signed an armistice agreement ending the war between them, Hanagah again tasked operatives with investigating “water sources [and] central reservoirs,” in Beirut, and “supplying maps of water pipelines” in major Lebanese and Syrian towns.

“It’s a trick…”

Clearly, then, there was very obviously a “point” to the poisoning program from the perspective of Ben-Gurion et al.

The connivance allowed the Zionists to efficaciously seize Palestinian territory, evicting Arabs from lands they had inhabited for centuries and deterring them from coming back, without firing a shot. Neither their victims – nor the international community – had no idea that the community-threatening epidemics seizing much of the region were man-made, rather than naturally occurring, either.

While it is clear from the paper certain individual militants were horrified by Cast Thy Bread and sought to curtail its operation, the relative lack of casualties cannot be chalked down to humanitarian concerns. Senior Zionists knew well the dire effects those infected by the bacteria suffered, not least because several of their own operatives contracted typhus themselves after accidentally drinking bottles containing it, believing the contents to be “gazoz”, a popular carbonated drink in the Middle East then and now.

Instead, Cast Thy Bread helped conceal the settlers’ long-term objectives of annexing land far in excess of that which had been proposed under the UN partition plan, including Palestinian territory and portions of neighboring Arab countries. Clandestine use of low death rate biological weapons meant a mass purge of civilians from these areas would appear to be voluntary and self-initiated, and could be secured without the need for large-scale massacres, or local residents being evicted at gunpoint en masse.

Ben-Gurion spelled out the Zionists’ true territorial ambitions in October 1937, following publication of Britain’s Peel Commission findings, which first advocated partitioning Palestine between Arabs and Jews. He supported the proposal, “because this increase in possession is of consequence not only in itself, but because through it we increase our strength, and every increase in strength helps in the possession of the land as a whole.”

Such honesty is vanishingly rare. Obscuring at all times the genocidal character of Zionism, which underpins and is absolutely fundamental to the colonial ideology, has been of the utmost importance to all its adherents ever since its inception. It is an ever-increasingly difficult facade to maintain, as the days of employing covert techniques to purge Israel and the territories it illegally occupies of Arabs are largely over. Instead, the slow-burn annihilation of Palestinians is conducted overwhelmingly in broad daylight.

As former British Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn and his supporters found out to their immense personal, professional and political cost, the primary means by which Israel shields its systematic ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from public scrutiny and condemnation today is via bogus accusations of anti-Semitism against detractors. Shulamit Aloni, former Israeli Education Minister and winner of the Israel Prize, explained to Democracy Now! in 2002:

It’s a trick, we always use it. When from Europe somebody is criticizing Israel, then we bring up the Holocaust. When in [the U.S.] people are criticizing Israel, then they are anti-Semitic…It’s very easy to blame people who criticize certain acts of the Israeli government as anti-Semitic, and to bring up the Holocaust, and the suffering of the Jewish people, and that is to justify everything we do to the Palestinians.”

The material collated by Morris and Kedar suggests this is a long-established “trick”. On May 27, 1948, Egypt’s Minister of Foreign Affairs sent a cable to the UN Secretary General, revealing that the previous day his country’s soldiers had captured two “Zionist agents” who were attempting to contaminate springs “from which the Egyptian troops at Gaza draw their water supply,” and had “dropped typhoid and dysentery germs into the wells lying to the east of that town.”

The cable, intercepted by Hanagan, was read out at a UN Security Council meeting later that day by Syria’s representative. In response, Major Aubrey Eban, designated representative of the Jewish Agency for Palestine (Israel had not yet been internationally recognized and was not a member state at that time), offered a vicious riposte.

He charged that the Egyptian and Syrian governments had “chosen to associate themselves with the most depraved tradition of medieval anti-Semitic incitement – the charge that Jews had poisoned Christian wells.”

“The Security Council, we are convinced, will not wish to become a tribunal for recitations from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion offered from the words of Dr. Goebbels. We hope that the Security Council will be interested not in this contemptible incitement, but in the reality of [Arab] bombs and shells falling on Jerusalem and Tel Aviv at this moment,” he added furiously.

Such an intervention may account for why, after initial press interest in the two diplomats’ caustic war of words, Cast Thy Bread remained successfully buried for almost seven-and-a-half decades subsequently, despite opaque references to the monstrous machination appearing in several autobiographies of Zionist leaders and militants from the time, and a 2003 academic article.

Indeed, the operation was so secret that even Israeli government censors were apparently unaware of its existence, so allowed numerous highly incriminating papers referencing the operation’s codename to pass by them unexpurgated, straight into the publicly accessible archives of the Israeli Occupation Forces.

Reinforcing the significance of Operation Cast Thy Bread, and the eager Zionist embrace of its grisly constituent techniques, HEMED’s biological warfare division became the formally civilian Institute for Biological Research in Nes Ziona, a town in central Israel, after the 1948 War ended. Its first director was former Haganah officer Alexander Keynan, who was intimately involved in the planning and execution of “Bread”.

Little is known about the extent or nature of Israeli biological weapons research or development today. The Institute for Biological Research has remained largely hidden from public view ever since launch, not least due to extensive security measures blocking outsider access. British investigative journalist Gordon Thomas has described a site over which no aircraft are allowed to fly, and scientists toil in laboratories deep underground creating “bottled agents of death.”

Nonetheless, it may be significant that modern Israel is one of very, very few countries in the world that is neither a signatory to the 1975 Biological Weapons Convention nor the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention. Could another “Cast Thy Bread” be in the literal and proverbial pipeline? At the very least, we have no reason to think it won’t be. If such a campaign was to be waged now, it would likely escape public detection even more effectively than last time.

A striking aspect of Palestinian writing about the 1948 War, identified by Morris and Kedar, is an almost total lack of reference to epidemic outbreaks at the time at all. Surviving victims of the Nakba today who contracted typhoid at the time, or had friends and relatives who did, now face the renewed indignity of learning, 74 years after the fact, they were deliberately poisoned.

Kit Klarenberg is an investigative journalist and MintPresss News contributor exploring the role of intelligence services in shaping politics and perceptions.