Taibbi: The Death Of Humor

Authored by Matt Taibbi via TK News,

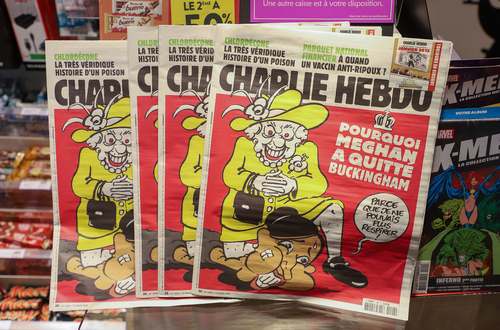

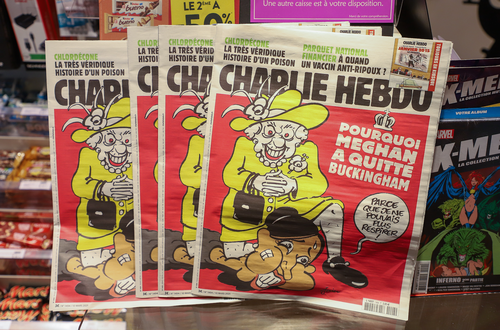

The French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo won the condemnation of the whole world again, with the cover pictured above. Reactions ranged from “abhorrent” to “hateful” to “wrong on every level,” with many offering versions of the now-mandatory observation that the magazine is not only bad now, but “has always been disgusting.”

This cover is probably an 8 or 9 on the offensiveness scale, and I laughed. It goes after everyone: Queen Elizabeth, depicted as a more deranged version of Derek Chauvin (the stubby leg hairs are a nice touch); Meghan Markle, the princess living in incomparable luxury whose victimhood has become a global pop-culture fixation; and, most of all, the inevitable chorus of outraged commentators who’ll insist they “enjoy good satire as much as the next person” but just can’t abide this particular effort that “goes too far,” it being just a coincidence that none of these people have laughed since grade school and don’t miss it.

Review of Killer Cartoons, edited by David Wallis, and White, by Bret Easton Ellis

Six years ago, after terrorists killed 10 people at Hebdo’s Paris offices in a brutal gun attack, the paper’s writers, editors, and cartoonists were initially celebrated worldwide as martyrs to the cause of free speech and democratic values. In France alone on January 11, 2015, over 3 million people marched in a show of solidarity with the victims, who’d been killed for drawing pictures of the Prophet Muhammad. Protesters also marched in defiance of those who would shoot people for drawing cartoons, especially since this particular group of killers also fatally shot four people at a kosher supermarket in an anti-Semitic attack. For about five minutes, Je Suis Charlie was a rallying cry around the world.

In an early preview of the West’s growing sympathy for eliminating heretics, cracks quickly appeared in the post-massacre defense of Charlie Hebdo. Pope Francis said that if someone “says a curse word against my mother, he can expect a punch.” Bill Donohoe, head of the American Catholic League, wrote, “Muslims are right to be angry,” and said of Hebdo editor Stephane Charbonnier, “Had he not been so narcissistic, he may still be alive.” New York Times columnist and noted humor expert David Brooks wrote an essay, “I Am Not Charlie Hebdo,” arguing that although “it’s almost always wrong to try to suppress speech,” these French miscreants should be excluded from polite society, and consigned to the “kids’ table,” along with Bill Maher and Ann Coulter.

Humor is dying all over, for obvious reasons. All comedy is subversive and authoritarianism is the fashion. Comics exist to keep us from taking ourselves too seriously, and we live in an age when people believe they have a constitutional right to be taken seriously, even if — especially if — they’re idiots, repeating thoughts they only just heard for the first time minutes ago. Because humor deflates stupid ideas, humorists are denounced in all cultures that worship stupid ideas, like Spain under the Inquisition, Afghanistan under the Taliban, or today’s United States.

During the Trump era, there was a steep decline of jokes overall, but mockery of a president who’d say things like, “My two greatest assets have been mental stability and being, like, really smart” rose to unprecedented levels. It was not only okay to laugh at Trump, it was mandatory, and the more tasteless the imagery, the better: Trump gay with Putin, Trump gay with the Klan, Trump with micropenis, Trump’s face as mosaic of 500 dicks, Trump as a blind man led by a seeing-eye dog who has the face of Benjamin Netanyahu and a Star of David hanging off his collar, Trump with a pen up his ass, Trump with tiny penis again. Pundits guffawed even more when someone threatened to sue artist Illma Gore for her “Trump’s tiny weiner” pastel, displayed at the Maddox Gallery in London. “It is my art and I stand by it,” Gore said. “Plus anyone who is afraid of a fictional penis is not scary to me.”

People cheered, because of course: anyone who even threatens to hire a lawyer to denounce a drawing has already lost. Cartoonists in this sense had no better friend than Trump, who constantly tried to block unfriendly renderings, including a Nick Anderson cartoon showing him and his followers drinking bleach as a Covid-19 cure (the Trump campaign reportedly called Anderson’s drawing of MAGA hats a trademark infringement). A lot of the anti-Trump cartoons were neither creative nor funny — if “He’s gay and has a little dick!” is the best you can do with that politician, you probably need a new line of work — and were only rescued by Trump’s preposterous efforts to defend his dignity. You can’t police a person’s private instinct to laugh, and there’s nothing funnier than watching someone try, especially if that person is already a sort-of billionaire and the president.

For all that, most of the jokes of the Trump era fell flat, precisely because they were obligatory. Modern humorists are allowed to laugh at bad people: racists, sexists, conspiracy theorists, Trump, anyone but themselves or the audience. There were artists who made great humor out of Trump. “Mr. Garrison snorts amyl nitrate while raping Trump to death” stood out, while Anthony Atamaniuk’s impersonations worked because he genuinely tried to connect with the Trump in all of us, asking, “Where’s the Trump part of my psyche?” But most Trump humor was just DNC talking points in sketch form, about as funny as WWII caricatures of Tojo or Hitler.

Saturday Night Live even commemorated the release of the Mueller report and the death of the collusion theory not by making fun of themselves, or the thousands of pundits, politicians, and other public figures who spent three years insisting it was true, but by doing yet another “Shirtless Putin” skit, with mournful Putin declaring, “I am still powerful guy, even if Trump doesn’t work for me!” I defy anyone to watch this and declare it was written by a comedian, and not someone like David Brock, or an Adam Schiff intern:

Humorists once made their livings airing out society’s forbidden thoughts, back when it was understood that a) we all had them and b) the things we suppressed and made us the most anxious also tended to be the things that made us laugh the most. Which brings us to Killed Cartoons: Casualties From the War on Free Expression.

Editor David Wallis put Killed Cartoons together in 2007, not long after the controversy involving the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, which published a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed in September 2005. Wallis noted that American coverage of the controversy assiduously avoided showing the offending cartoons — I noted the same thing after the Hebdo massacre — which Pulitzer-winning cartoonist Doug Marlette insisted was tantamount to acquiescing to mob rule. This instinct is now ingrained in American journalism. On an almost daily basis, a public figure is forced to confess to various crimes against political orthodoxy, but readers are seldom told what exactly they’ve done, only that it was bad. Jay Leno is the latest to offer the Groveling Public Confession for what the New York Times only called “years of anti-Asian jokes,” without telling us what they were.

The confession was set in motion by a profile of actor and producer Gabrielle Union in Variety, in which she recounted an exchange between Leno and Simon Cowell in the offices of America’s Got Talent:

While filming a commercial interstitial in the “AGT” offices, she says the former “Tonight Show” host made a crack about a painting of Cowell and his dogs, saying the animals looked like food items at a Korean restaurant. The joke was widely perceived as perpetuating stereotypes about Asian people eating dog meat.

The Media Action Network for Asian Americans (MANAA) compiled “nine documented jokes” between 2002 and 2012 Leno made about Koreans or Chinese eating dog meat. (Koreans and Chinese do eat dog meat — there are even dog meat festivals — but whatever).

Rejected jokes weren’t hard to find even in the early 2000s because, Wallis wrote, editors “suppress compelling illustrations, editorial cartoons, and political comics out of fear — fear of angering advertisers, the publisher’s golf partners, the publisher’s wife, the local dogcatcher or the president of the United States, blacks, Asians, Hispanics, homophobes, gays, pro-choice advocates and antiabortion protesters alike, Catholics, Jews, and midwestern grannies…”

Even back in the 1990s and early 2000s, the “respectable” press often nixed cartoons precisely because they were funny. A genuine laugh to editors was a sign of trouble. Wallis tells of a cartoonist named J.P. Trostle from the Chapel Hill Herald, who in October 2001 tried to sell a cartoon in advance of a local Halloween Street party. “Unwise Halloween Costumes,” was the headline, above a picture of a boy trick-or-treating as a box of anthrax, and a couple at a keg party dressed as the Twin Towers (the man had a beanie hat with a dangling airplane). Wallis describes how Trostle showed sketches to editors and reporters hoping to build support. “The first thing they did was laugh at it,” he said. “The second thing they did was [say], ‘We are never going to run this.’”

It was the same thing when Bob Englehardt tried to test the statute of limitations on Holocaust humor. “Schindler’s Other List” was just a piece of paper with the words Eggs, Milk, Coffee, Bread on it — obviously funny, but killed by the Hartford Courant in 1993. There are many other stories involving ideas that were just a little too much like laughing at real things for newspaper editors even a generation ago, like Christ carrying an electric chair up a hill, the Pope ascending to heaven in a plexiglass-covered chariot, or another Pope (Popes are funny) holding a staff in the shape of a coat hanger.

Killed Cartoons is a history of a time when editors and cartoonists alike were trying to toe the line between what people found funny in private, and what was considered acceptable fodder for public ridicule. We’re way past that now, when we’re not supposed to have unwholesome thoughts either in public or in private. In fact, the whole concept of private thoughts has become infamous. Why does anyone need private opinions, in a society where the right opinions on every question are known, and should be safe to say publicly?

“A cultural low point of 2015,” wrote Bret Easton Ellis in White, “was the effort by at least two hundred members of PEN America, a leading literary organization to which most writers belong, to not present the survivors of the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris with a newly established Freedom of Expression Courage Award.”

Ellis, whose 2019 book attracted even more public disgust than Charlie Hebdo’s latest cover, went on to blast the writers who decided honoring Hebdo would be “valorizing selectively offensive material.” The award was ultimately given, because there were more PEN members who believed the magazine deserved the award, but, Ellis wrote:

There were still two hundred who were offended and felt Charlie Hebdo went “too far” in its satire, which suggested there was a limited number of targets that humorists and satirists were allowed to pursue.

It made sense that Ellis would be upset about Americans disowning Charlie Hebdo. He’s famous for producing maybe the last unashamedly tasteless work of satire to win critical acclaim in this country. American Psycho was successful in part because so many of the people who found it so entertaining didn’t realize they were being stabbed or chainsawed in its pages. That book was about what happens when a society governed by openly insane values requires its citizens to wear a mask of normalcy. The deeper you try to bury the contradictions, the worse the sickness gets, and the book argued we were very sick already by the late eighties and early nineties.

In White, Ellis describes the Wall Street bros he tried to study for American Psycho. They were straight white dudes who traveled in packs and probably grew up bullying anyone who was different using words like “faggot,” but now, as the cadet-corps leaders of “youthful ‘80s Reagan-era excess,” they appropriated “the standard hallmarks of gay male culture” rather than talk about who they really were:

During my initial research I’d been frustrated by their evasions about what exactly they did for the companies where they worked — information I felt was necessary, but finally realized really wasn’t. I was surprised instead by their desire to show off their crazy materialistic lifestyles: the hip, outrageously priced restaurants they could get reservations at, the cool Hamptons summer rentals and, especially, their expensive haircuts and tanning regimens and gym memberships and grooming routines.

American Psycho was a book that many people loved, so long as they were certain it described someone else, a monster. In fact, what made the humor work, and elevated it above a compendium of snide put-downs of Wall Street jerks, was that it described an inner monologue familiar to most of us.

In a country that worshipped the Nike image of the fit, informed, socially-concerned go-getter, but really judged us by our skill in crushing neighbors as capitalist competitors and fleecing the public as dupes — without question, Pierce and Pierce would eventually have been a leading marketer of mortgage-backed securities — the book’s serial killer hero Patrick Bateman was an utterly typical exemplar of the American species. The realization of his ordinariness, of society’s lack of interest or surprise at his murderous inner life, was central to the protagonist’s horrific punchline epiphany.

Ellis talks about how things in this country haven’t changed since American Psycho, but are “more exaggerated, more accepted.” Would the more heavily-surveilled America we live in now “prevent [Bateman] from getting away with the murders he at least tells the reader he’s committed…?” He’d at least have to work harder at his disguise. Would he “haunt social media as a troll using fake avatars… have a Twitter account bragging about his accomplishments”? Ellis notes that “during Patrick’s 80’s reign, he still had the ability to hide, a possibility that simply doesn’t exist in our fully exhibitionist society.”

In American Psycho, Bateman is a monster in private, and everything else is mask, from his spearmint facial scrub to his fake tan to his interminable conversations about business card fonts and rehearsed opinions on everything from feeding the homeless and achieving world peace.

In 2021, we’re all mask, and it shines through in White that what drives Ellis batty is that modern Americans not only believe the phony opinions they get from memorizing the latest sacred texts of the Times bestseller list (a fashion obsession no different from the Zegna suits worshipped by the American Psycho bros), but require that everyone else believe them too.

The penalties for deviance were once mostly self-imposed, by people who feared losing a little social status — “I want to fit in,” Bateman explained — but any person who wants to earn a living now must recite The Pieties, or else. Even someone like James Gunn, director of The Guardians of the Galaxy, someone who made over a billion dollars for his employers, could be fired for tweeting jokes like “Three Men and a Baby They Had Sex With #unromantic movies” and “The Hardy Boys and The Mystery of What It Feels Like When Uncle Bernie Fists Me #SadChildrensBooks.” Gunn’s idea for an alternate ending to The Giving Tree — “the tree grows back and gives the kid a blowjob” — seemed funny to me until I learned that a serious movement was really underway to “rethink” the book.

Author Shel Silverstein mainly just hated happy endings, but now stands accused of having created a model for abusive relationships in the story of a tree that keeps giving apples to a kid, who keeps taking them. “You don’t have to give until it hurts” chided one New York Times columnist, to child readers and, I guess, trees.

In a genuinely comic development, Gunn was re-hired, mainly because his initial firing was the result of a conservative prank. Right-wing provocateurs like Mike Cernovich and Jack Posobiec correctly guessed Hollywood could be conned into firing even a major rainmaker over nonsense. When Gunn was rehabilitated, the press cast him as a martyr to the cause of anti-Trumpism, targeted by right-wing fiends who “combed through Gunn’s social media history after Gunn’s criticism of President Donald Trump.” Meanwhile, one of the film’s stars, Chris Pratt, is still fighting off his own controversy, which literally started with a joke — which Hollywood Chris should be fired, a Tweeter asked — and morphed into a serious “backlash” in which Forbes explained that Pratt’s decision to not attend a virtual fundraiser for Joe Biden “has led to the belief that Pratt is secretly a Trump supporter.”

White came out two years ago, in April of 2019, and was reviewed savagely. Critics from Vox to NPR to the Guardian agreed White was the work of a bitter has-been sexist and misogynist whose “rambling mess of cultural commentary and self-aggrandizement” might never have been published if, Bookforum’s Andrea Long Chu suggested, “Ellis’s millennial boyfriend had simply shown the famous man how to use the mute feature on Twitter.” Virtually every review was a Mad Libs exercise in rearranging words like old, whiny, rich, petty, aggrieved, and boring (reviewers universally agreed the book was boring).

Every review focused on the politics of the book, describing as a tirade against cancel culture, left censorship, “snowflakes,” and “hysterics” who can’t take criticism. Ellis’s invocation of the term “Generation Wuss” to describe millennials, who do not come off well either in the book or in the interviews he gave after its release, figures in almost every review by younger writers, who of course gave back in kind. In a format that’s by now standard when criticizing almost any brand of transgressing celebrity, from Pratt to Ellen DeGeneres to Kirstie Alley, reviewers made a point of reminding us that not only is Ellis terrible now, but that on some level he’s always been terrible, even when we thought he was good. Bookforum even managed to wing J.D. Salinger in the crossfire.

“Like The Catcher in the Rye before it and Fight Club after it,” the site wrote, “American Psycho is a book designed to convince comfortable white men that they are, in fact, ‘outsiders and monsters and freaks.’” (That the book was about the opposite — a world where “no one can tell anyone else apart” and even ax-murdering Patrick Bateman ultimately learns he’s just a face in the crowd — is irrelevant). The strongest sentiment in all the reviews was a desire that Ellis just shut the fuck up. “One longs to tell him what the Rolling Stones told Trump: Please stop,” wrote Chu. NPR got more to the point. “Most of us carry around an invisible rosary of resentments to fiddle with in petty moments,” wrote Annalisa Quinn. “Most of us also know to keep these grudges private.”

The actual dictum isn’t just to keep unwelcome thoughts private, but to not have them at all. But people can’t control what they find funny. In Killed Cartoons, an African-American cartoonist describes bringing a cartoon depicting him sharing a giant bag of crack with prostitutes to an editor. “Why do you have to say that?” the editor asked. What’s the message? “It’s funny!” he replied. “It’s a giant bag of crack!” The panel ended up rejected, for fear of offending the paper’s “large white liberal readership.”

The new movement thinks it’s stamping out harmful jokes about disadvantaged groups, but truly cruel or bigoted material tends not to win real laughs. There are exceptions — people thought Eddie Murphy’s “faggots will kick your ass” jokes were funny once — but what people mostly laugh at are things that are true, which is the problem with telling people you can’t think or laugh about funny things even in private. People will either go mad, or else they’ll start laughing at you, which is why we’re already seeing something I never thought I would in my lifetime — the humor business drifting into the arms of conservatives. Humor is about saying the unsayable, and most of the comics who insist on still doing it are either denounced as reactionaries, like Charlie Hebdo or Joe Rogan or even Dave Chappelle, or else they were openly conservative to begin with. The Babylon Bee is marketed as something from one of my childhood nightmares (“Your trusted source for Christian news satire”), and the fact that it’s now exponentially more likely to be funny than Stephen Colbert feels like a sign of the End-Times.

In White, Ellis writes about the seemingly inexplicable appeal of Charlie Sheen in Two and a Half Men, writing that his stunned disgust as he “staggered amiably through a bad sitcom” was what attracted audiences, because “not giving a fuck about what the public thinks about you or your personal life is actually what matters most… the public will respond to you because you’re free and that’s exactly what they all desire.” People are attracted to humorists for the same reason; they’re saying what we can’t. If there’s no room for such people anymore, we’re in a lot of trouble. People can only go without laughing for so long.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 03/27/2021 – 15:30

Taibbi: The Death Of Humor

Authored by Matt Taibbi via TK News,

The French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo won the condemnation of the whole world again, with the cover pictured above. Reactions ranged from “abhorrent” to “hateful” to “wrong on every level,” with many offering versions of the now-mandatory observation that the magazine is not only bad now, but “has always been disgusting.”

This cover is probably an 8 or 9 on the offensiveness scale, and I laughed. It goes after everyone: Queen Elizabeth, depicted as a more deranged version of Derek Chauvin (the stubby leg hairs are a nice touch); Meghan Markle, the princess living in incomparable luxury whose victimhood has become a global pop-culture fixation; and, most of all, the inevitable chorus of outraged commentators who’ll insist they “enjoy good satire as much as the next person” but just can’t abide this particular effort that “goes too far,” it being just a coincidence that none of these people have laughed since grade school and don’t miss it.

Review of Killer Cartoons, edited by David Wallis, and White, by Bret Easton Ellis

Six years ago, after terrorists killed 10 people at Hebdo’s Paris offices in a brutal gun attack, the paper’s writers, editors, and cartoonists were initially celebrated worldwide as martyrs to the cause of free speech and democratic values. In France alone on January 11, 2015, over 3 million people marched in a show of solidarity with the victims, who’d been killed for drawing pictures of the Prophet Muhammad. Protesters also marched in defiance of those who would shoot people for drawing cartoons, especially since this particular group of killers also fatally shot four people at a kosher supermarket in an anti-Semitic attack. For about five minutes, Je Suis Charlie was a rallying cry around the world.

In an early preview of the West’s growing sympathy for eliminating heretics, cracks quickly appeared in the post-massacre defense of Charlie Hebdo. Pope Francis said that if someone “says a curse word against my mother, he can expect a punch.” Bill Donohoe, head of the American Catholic League, wrote, “Muslims are right to be angry,” and said of Hebdo editor Stephane Charbonnier, “Had he not been so narcissistic, he may still be alive.” New York Times columnist and noted humor expert David Brooks wrote an essay, “I Am Not Charlie Hebdo,” arguing that although “it’s almost always wrong to try to suppress speech,” these French miscreants should be excluded from polite society, and consigned to the “kids’ table,” along with Bill Maher and Ann Coulter.

Humor is dying all over, for obvious reasons. All comedy is subversive and authoritarianism is the fashion. Comics exist to keep us from taking ourselves too seriously, and we live in an age when people believe they have a constitutional right to be taken seriously, even if — especially if — they’re idiots, repeating thoughts they only just heard for the first time minutes ago. Because humor deflates stupid ideas, humorists are denounced in all cultures that worship stupid ideas, like Spain under the Inquisition, Afghanistan under the Taliban, or today’s United States.

During the Trump era, there was a steep decline of jokes overall, but mockery of a president who’d say things like, “My two greatest assets have been mental stability and being, like, really smart” rose to unprecedented levels. It was not only okay to laugh at Trump, it was mandatory, and the more tasteless the imagery, the better: Trump gay with Putin, Trump gay with the Klan, Trump with micropenis, Trump’s face as mosaic of 500 dicks, Trump as a blind man led by a seeing-eye dog who has the face of Benjamin Netanyahu and a Star of David hanging off his collar, Trump with a pen up his ass, Trump with tiny penis again. Pundits guffawed even more when someone threatened to sue artist Illma Gore for her “Trump’s tiny weiner” pastel, displayed at the Maddox Gallery in London. “It is my art and I stand by it,” Gore said. “Plus anyone who is afraid of a fictional penis is not scary to me.”

People cheered, because of course: anyone who even threatens to hire a lawyer to denounce a drawing has already lost. Cartoonists in this sense had no better friend than Trump, who constantly tried to block unfriendly renderings, including a Nick Anderson cartoon showing him and his followers drinking bleach as a Covid-19 cure (the Trump campaign reportedly called Anderson’s drawing of MAGA hats a trademark infringement). A lot of the anti-Trump cartoons were neither creative nor funny — if “He’s gay and has a little dick!” is the best you can do with that politician, you probably need a new line of work — and were only rescued by Trump’s preposterous efforts to defend his dignity. You can’t police a person’s private instinct to laugh, and there’s nothing funnier than watching someone try, especially if that person is already a sort-of billionaire and the president.

For all that, most of the jokes of the Trump era fell flat, precisely because they were obligatory. Modern humorists are allowed to laugh at bad people: racists, sexists, conspiracy theorists, Trump, anyone but themselves or the audience. There were artists who made great humor out of Trump. “Mr. Garrison snorts amyl nitrate while raping Trump to death” stood out, while Anthony Atamaniuk’s impersonations worked because he genuinely tried to connect with the Trump in all of us, asking, “Where’s the Trump part of my psyche?” But most Trump humor was just DNC talking points in sketch form, about as funny as WWII caricatures of Tojo or Hitler.

Saturday Night Live even commemorated the release of the Mueller report and the death of the collusion theory not by making fun of themselves, or the thousands of pundits, politicians, and other public figures who spent three years insisting it was true, but by doing yet another “Shirtless Putin” skit, with mournful Putin declaring, “I am still powerful guy, even if Trump doesn’t work for me!” I defy anyone to watch this and declare it was written by a comedian, and not someone like David Brock, or an Adam Schiff intern:

Humorists once made their livings airing out society’s forbidden thoughts, back when it was understood that a) we all had them and b) the things we suppressed and made us the most anxious also tended to be the things that made us laugh the most. Which brings us to Killed Cartoons: Casualties From the War on Free Expression.

Editor David Wallis put Killed Cartoons together in 2007, not long after the controversy involving the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, which published a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed in September 2005. Wallis noted that American coverage of the controversy assiduously avoided showing the offending cartoons — I noted the same thing after the Hebdo massacre — which Pulitzer-winning cartoonist Doug Marlette insisted was tantamount to acquiescing to mob rule. This instinct is now ingrained in American journalism. On an almost daily basis, a public figure is forced to confess to various crimes against political orthodoxy, but readers are seldom told what exactly they’ve done, only that it was bad. Jay Leno is the latest to offer the Groveling Public Confession for what the New York Times only called “years of anti-Asian jokes,” without telling us what they were.

The confession was set in motion by a profile of actor and producer Gabrielle Union in Variety, in which she recounted an exchange between Leno and Simon Cowell in the offices of America’s Got Talent:

While filming a commercial interstitial in the “AGT” offices, she says the former “Tonight Show” host made a crack about a painting of Cowell and his dogs, saying the animals looked like food items at a Korean restaurant. The joke was widely perceived as perpetuating stereotypes about Asian people eating dog meat.

The Media Action Network for Asian Americans (MANAA) compiled “nine documented jokes” between 2002 and 2012 Leno made about Koreans or Chinese eating dog meat. (Koreans and Chinese do eat dog meat — there are even dog meat festivals — but whatever).

Rejected jokes weren’t hard to find even in the early 2000s because, Wallis wrote, editors “suppress compelling illustrations, editorial cartoons, and political comics out of fear — fear of angering advertisers, the publisher’s golf partners, the publisher’s wife, the local dogcatcher or the president of the United States, blacks, Asians, Hispanics, homophobes, gays, pro-choice advocates and antiabortion protesters alike, Catholics, Jews, and midwestern grannies…”

Even back in the 1990s and early 2000s, the “respectable” press often nixed cartoons precisely because they were funny. A genuine laugh to editors was a sign of trouble. Wallis tells of a cartoonist named J.P. Trostle from the Chapel Hill Herald, who in October 2001 tried to sell a cartoon in advance of a local Halloween Street party. “Unwise Halloween Costumes,” was the headline, above a picture of a boy trick-or-treating as a box of anthrax, and a couple at a keg party dressed as the Twin Towers (the man had a beanie hat with a dangling airplane). Wallis describes how Trostle showed sketches to editors and reporters hoping to build support. “The first thing they did was laugh at it,” he said. “The second thing they did was [say], ‘We are never going to run this.’”

It was the same thing when Bob Englehardt tried to test the statute of limitations on Holocaust humor. “Schindler’s Other List” was just a piece of paper with the words Eggs, Milk, Coffee, Bread on it — obviously funny, but killed by the Hartford Courant in 1993. There are many other stories involving ideas that were just a little too much like laughing at real things for newspaper editors even a generation ago, like Christ carrying an electric chair up a hill, the Pope ascending to heaven in a plexiglass-covered chariot, or another Pope (Popes are funny) holding a staff in the shape of a coat hanger.

Killed Cartoons is a history of a time when editors and cartoonists alike were trying to toe the line between what people found funny in private, and what was considered acceptable fodder for public ridicule. We’re way past that now, when we’re not supposed to have unwholesome thoughts either in public or in private. In fact, the whole concept of private thoughts has become infamous. Why does anyone need private opinions, in a society where the right opinions on every question are known, and should be safe to say publicly?

“A cultural low point of 2015,” wrote Bret Easton Ellis in White, “was the effort by at least two hundred members of PEN America, a leading literary organization to which most writers belong, to not present the survivors of the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris with a newly established Freedom of Expression Courage Award.”

Ellis, whose 2019 book attracted even more public disgust than Charlie Hebdo’s latest cover, went on to blast the writers who decided honoring Hebdo would be “valorizing selectively offensive material.” The award was ultimately given, because there were more PEN members who believed the magazine deserved the award, but, Ellis wrote:

There were still two hundred who were offended and felt Charlie Hebdo went “too far” in its satire, which suggested there was a limited number of targets that humorists and satirists were allowed to pursue.

It made sense that Ellis would be upset about Americans disowning Charlie Hebdo. He’s famous for producing maybe the last unashamedly tasteless work of satire to win critical acclaim in this country. American Psycho was successful in part because so many of the people who found it so entertaining didn’t realize they were being stabbed or chainsawed in its pages. That book was about what happens when a society governed by openly insane values requires its citizens to wear a mask of normalcy. The deeper you try to bury the contradictions, the worse the sickness gets, and the book argued we were very sick already by the late eighties and early nineties.

In White, Ellis describes the Wall Street bros he tried to study for American Psycho. They were straight white dudes who traveled in packs and probably grew up bullying anyone who was different using words like “faggot,” but now, as the cadet-corps leaders of “youthful ‘80s Reagan-era excess,” they appropriated “the standard hallmarks of gay male culture” rather than talk about who they really were:

During my initial research I’d been frustrated by their evasions about what exactly they did for the companies where they worked — information I felt was necessary, but finally realized really wasn’t. I was surprised instead by their desire to show off their crazy materialistic lifestyles: the hip, outrageously priced restaurants they could get reservations at, the cool Hamptons summer rentals and, especially, their expensive haircuts and tanning regimens and gym memberships and grooming routines.

American Psycho was a book that many people loved, so long as they were certain it described someone else, a monster. In fact, what made the humor work, and elevated it above a compendium of snide put-downs of Wall Street jerks, was that it described an inner monologue familiar to most of us.

In a country that worshipped the Nike image of the fit, informed, socially-concerned go-getter, but really judged us by our skill in crushing neighbors as capitalist competitors and fleecing the public as dupes — without question, Pierce and Pierce would eventually have been a leading marketer of mortgage-backed securities — the book’s serial killer hero Patrick Bateman was an utterly typical exemplar of the American species. The realization of his ordinariness, of society’s lack of interest or surprise at his murderous inner life, was central to the protagonist’s horrific punchline epiphany.

Ellis talks about how things in this country haven’t changed since American Psycho, but are “more exaggerated, more accepted.” Would the more heavily-surveilled America we live in now “prevent [Bateman] from getting away with the murders he at least tells the reader he’s committed…?” He’d at least have to work harder at his disguise. Would he “haunt social media as a troll using fake avatars… have a Twitter account bragging about his accomplishments”? Ellis notes that “during Patrick’s 80’s reign, he still had the ability to hide, a possibility that simply doesn’t exist in our fully exhibitionist society.”

In American Psycho, Bateman is a monster in private, and everything else is mask, from his spearmint facial scrub to his fake tan to his interminable conversations about business card fonts and rehearsed opinions on everything from feeding the homeless and achieving world peace.

In 2021, we’re all mask, and it shines through in White that what drives Ellis batty is that modern Americans not only believe the phony opinions they get from memorizing the latest sacred texts of the Times bestseller list (a fashion obsession no different from the Zegna suits worshipped by the American Psycho bros), but require that everyone else believe them too.

The penalties for deviance were once mostly self-imposed, by people who feared losing a little social status — “I want to fit in,” Bateman explained — but any person who wants to earn a living now must recite The Pieties, or else. Even someone like James Gunn, director of The Guardians of the Galaxy, someone who made over a billion dollars for his employers, could be fired for tweeting jokes like “Three Men and a Baby They Had Sex With #unromantic movies” and “The Hardy Boys and The Mystery of What It Feels Like When Uncle Bernie Fists Me #SadChildrensBooks.” Gunn’s idea for an alternate ending to The Giving Tree — “the tree grows back and gives the kid a blowjob” — seemed funny to me until I learned that a serious movement was really underway to “rethink” the book.

Author Shel Silverstein mainly just hated happy endings, but now stands accused of having created a model for abusive relationships in the story of a tree that keeps giving apples to a kid, who keeps taking them. “You don’t have to give until it hurts” chided one New York Times columnist, to child readers and, I guess, trees.

In a genuinely comic development, Gunn was re-hired, mainly because his initial firing was the result of a conservative prank. Right-wing provocateurs like Mike Cernovich and Jack Posobiec correctly guessed Hollywood could be conned into firing even a major rainmaker over nonsense. When Gunn was rehabilitated, the press cast him as a martyr to the cause of anti-Trumpism, targeted by right-wing fiends who “combed through Gunn’s social media history after Gunn’s criticism of President Donald Trump.” Meanwhile, one of the film’s stars, Chris Pratt, is still fighting off his own controversy, which literally started with a joke — which Hollywood Chris should be fired, a Tweeter asked — and morphed into a serious “backlash” in which Forbes explained that Pratt’s decision to not attend a virtual fundraiser for Joe Biden “has led to the belief that Pratt is secretly a Trump supporter.”

White came out two years ago, in April of 2019, and was reviewed savagely. Critics from Vox to NPR to the Guardian agreed White was the work of a bitter has-been sexist and misogynist whose “rambling mess of cultural commentary and self-aggrandizement” might never have been published if, Bookforum’s Andrea Long Chu suggested, “Ellis’s millennial boyfriend had simply shown the famous man how to use the mute feature on Twitter.” Virtually every review was a Mad Libs exercise in rearranging words like old, whiny, rich, petty, aggrieved, and boring (reviewers universally agreed the book was boring).

Every review focused on the politics of the book, describing as a tirade against cancel culture, left censorship, “snowflakes,” and “hysterics” who can’t take criticism. Ellis’s invocation of the term “Generation Wuss” to describe millennials, who do not come off well either in the book or in the interviews he gave after its release, figures in almost every review by younger writers, who of course gave back in kind. In a format that’s by now standard when criticizing almost any brand of transgressing celebrity, from Pratt to Ellen DeGeneres to Kirstie Alley, reviewers made a point of reminding us that not only is Ellis terrible now, but that on some level he’s always been terrible, even when we thought he was good. Bookforum even managed to wing J.D. Salinger in the crossfire.

“Like The Catcher in the Rye before it and Fight Club after it,” the site wrote, “American Psycho is a book designed to convince comfortable white men that they are, in fact, ‘outsiders and monsters and freaks.’” (That the book was about the opposite — a world where “no one can tell anyone else apart” and even ax-murdering Patrick Bateman ultimately learns he’s just a face in the crowd — is irrelevant). The strongest sentiment in all the reviews was a desire that Ellis just shut the fuck up. “One longs to tell him what the Rolling Stones told Trump: Please stop,” wrote Chu. NPR got more to the point. “Most of us carry around an invisible rosary of resentments to fiddle with in petty moments,” wrote Annalisa Quinn. “Most of us also know to keep these grudges private.”

The actual dictum isn’t just to keep unwelcome thoughts private, but to not have them at all. But people can’t control what they find funny. In Killed Cartoons, an African-American cartoonist describes bringing a cartoon depicting him sharing a giant bag of crack with prostitutes to an editor. “Why do you have to say that?” the editor asked. What’s the message? “It’s funny!” he replied. “It’s a giant bag of crack!” The panel ended up rejected, for fear of offending the paper’s “large white liberal readership.”

The new movement thinks it’s stamping out harmful jokes about disadvantaged groups, but truly cruel or bigoted material tends not to win real laughs. There are exceptions — people thought Eddie Murphy’s “faggots will kick your ass” jokes were funny once — but what people mostly laugh at are things that are true, which is the problem with telling people you can’t think or laugh about funny things even in private. People will either go mad, or else they’ll start laughing at you, which is why we’re already seeing something I never thought I would in my lifetime — the humor business drifting into the arms of conservatives. Humor is about saying the unsayable, and most of the comics who insist on still doing it are either denounced as reactionaries, like Charlie Hebdo or Joe Rogan or even Dave Chappelle, or else they were openly conservative to begin with. The Babylon Bee is marketed as something from one of my childhood nightmares (“Your trusted source for Christian news satire”), and the fact that it’s now exponentially more likely to be funny than Stephen Colbert feels like a sign of the End-Times.

In White, Ellis writes about the seemingly inexplicable appeal of Charlie Sheen in Two and a Half Men, writing that his stunned disgust as he “staggered amiably through a bad sitcom” was what attracted audiences, because “not giving a fuck about what the public thinks about you or your personal life is actually what matters most… the public will respond to you because you’re free and that’s exactly what they all desire.” People are attracted to humorists for the same reason; they’re saying what we can’t. If there’s no room for such people anymore, we’re in a lot of trouble. People can only go without laughing for so long.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 03/27/2021 – 15:30

Read More