By Andrew Korybko

The bloc’s dual purpose in jointly thwarting shared unconventional threats and pioneering comprehensive connectivity opportunities across the supercontinent enables it to function as the core of multipolarity in the 21st century.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s (SCO) heads of state summit in the Tajik capital of Dushanbe in mid-September celebrated the bloc’s twentieth-year anniversary. Originally known as the Shanghai Five, it brought together China and its four neighboring former Soviet Republics in order to resolve their outstanding border differences at the time. The successful completion of this process as well as Uzbekistan’s eventual inclusion in the group led to it being rebranded as the SCO and expanding its purpose.

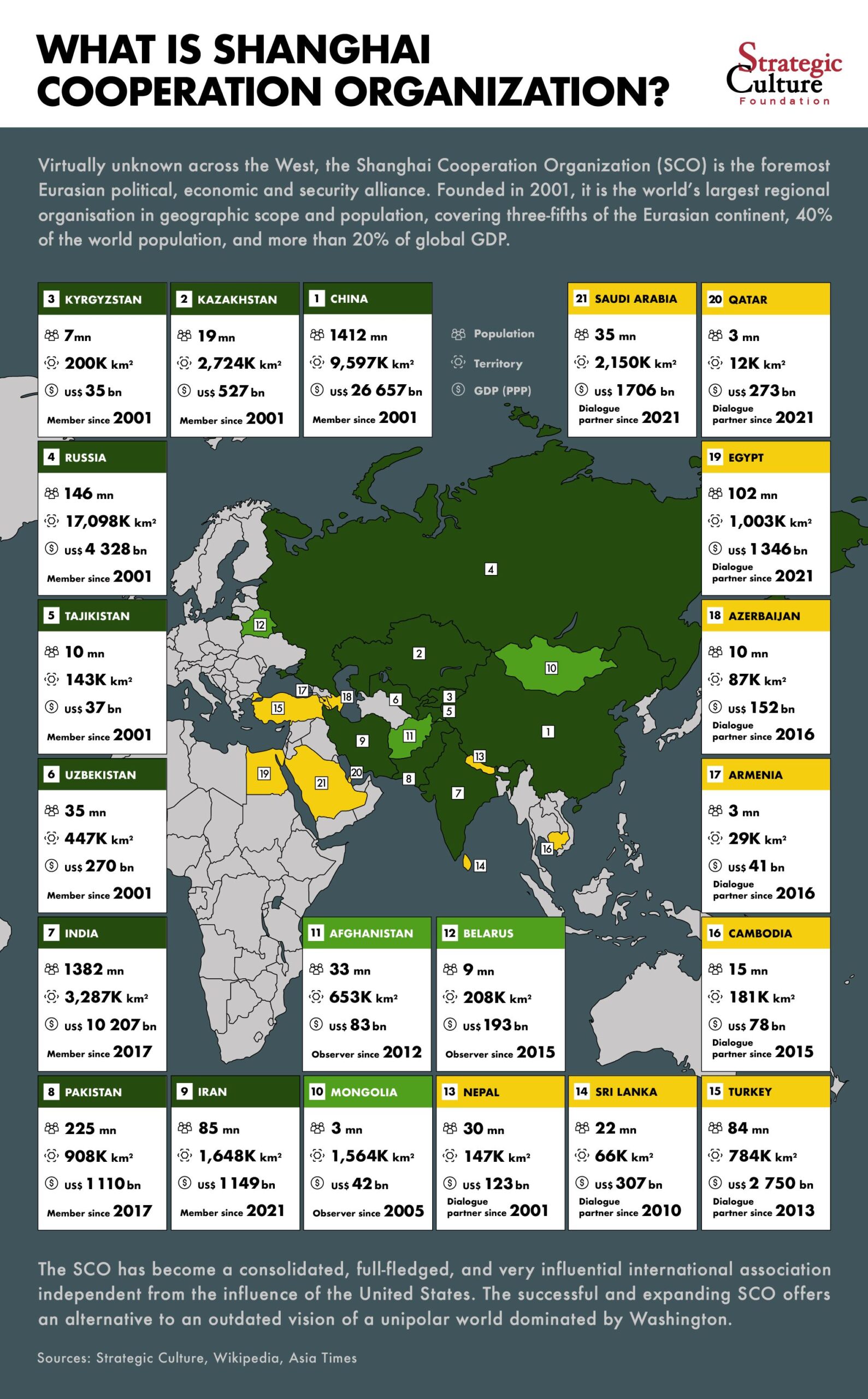

The SCO Charter emphasizes its members’ interests in jointly containing the three shared threats of separatism, terrorism, and extremism. The bloc has since expanded to include India, Iran, and Pakistan as formal members. Afghanistan, Belarus, and Mongolia are observers while Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Turkey are dialogue partners. The SCO is an inclusive organization that will continue to expand into the future since its goals align with those of all other peace-loving states endangered by such unconventional threats.

The SCO Charter emphasizes its members’ interests in jointly containing the three shared threats of separatism, terrorism, and extremism. The bloc has since expanded to include India, Iran, and Pakistan as formal members. Afghanistan, Belarus, and Mongolia are observers while Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Turkey are dialogue partners. The SCO is an inclusive organization that will continue to expand into the future since its goals align with those of all other peace-loving states endangered by such unconventional threats.

There’s more to the SCO than just its focus on ensuring hard security since the bloc has recently sought to promote comprehensive connectivity between its members. Many SCO members are also part of Beijing’s Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) and/or Moscow’s Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) so there’s a strong overlap of integration goals between them. For these reasons, they’re also cooperating on expanding commercial and financial linkages, which will bolster its members’ soft security by promoting their socio-economic stability.

Chinese President Xi Jinping endorsed this vision while addressing the summit by video. He urged the SCO countries to continue opening up and cooperating to facilitate each other’s development and vitalization. This will enable them to create a community of shared future for sustainably ensuring peace and common prosperity throughout the world. The Chinese leader observed how the bloc has already contributed in both theory and practice when it comes to building a new type of international relations.

President Xi is correct. What’s so special about the SCO is that it represents a new form of partnership in the emerging multipolar world order. Instead of being directed against any third parties and having an internal hierarchy like the US-led NATO and Quad for instance, it has no state-level opponents and its members are equal to one another. This bloc therefore embodies the principle of mutually beneficial (win-win) relations as opposed to the outdated notion of zero-sum ones that are always advanced at someone else’s expense.

Nowadays the greatest challenge for the SCO comes from post-war Afghanistan after the Taliban’s swift return to power there last month following the West’s chaotic withdrawal from the country. The SCO could contribute to Afghanistan’s soft security through the provisioning of socio-economic support to stave off its impending humanitarian crisis. Keep with the spirit of the SCO’s recent connectivity vision, its members could also seek to incorporate Taliban-led Afghanistan into their respective plans.

The SCO hasn’t ever faced a challenge quite like post-war Afghanistan before, but the bloc is expected to handle everything very efficiently. It’ll take time to see results, but some of its members like China, Pakistan, and Russia are already leading the way to help stabilize their shared partner. Through its focus on advancing complementary hard and soft security goals while respecting everyone’s sovereignty, the SCO will succeed where NATO failed in Afghanistan.

These goals could most directly be advanced through a combination of three means. First, the SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) could facilitate the sharing of relevant intelligence on drug, human-trafficking, and terrorist groups between the bloc’s members. Second, the SCO-Afghanistan Contact Group could play a greater role in managing Kabul’s ties with the organization and pioneering relevant socio-economic solutions such as the provisioning of much-needed humanitarian aid to those who most urgently need it.

Third, the SCO can cooperate with the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which is a mutual defense pact comprised of former Soviet Republics. There’s a close membership overlap within both platforms. All these countries are concerned about the risk of Afghan-emanating security threats, especially neighboring Tajikistan which participates in both platforms. These structures could therefore coordinate their relevant policies in order to avoid redundancies and thus enhance their overall effectiveness.

Altogether, it’s clear that the SCO is Eurasia’s most effective security organization and the only one capable of stabilizing Afghanistan, which others have unilaterally attempted to do for decades but have always failed. The bloc’s dual purpose in jointly thwarting shared unconventional threats and pioneering comprehensive connectivity opportunities across the supercontinent enables it to function as the core of multipolarity in the 21st century. President Xi was therefore correct in praising the SCO’s multifaceted contributions to the world.