Pakistan’s political, economic, and international uncertainties are all converging at the date of this prospective trip, the outcome of whether (not to mention whether or not it takes place) will disproportionately shape perceptions about its strategic trajectory following former Prime Minister Khan’s ouster.

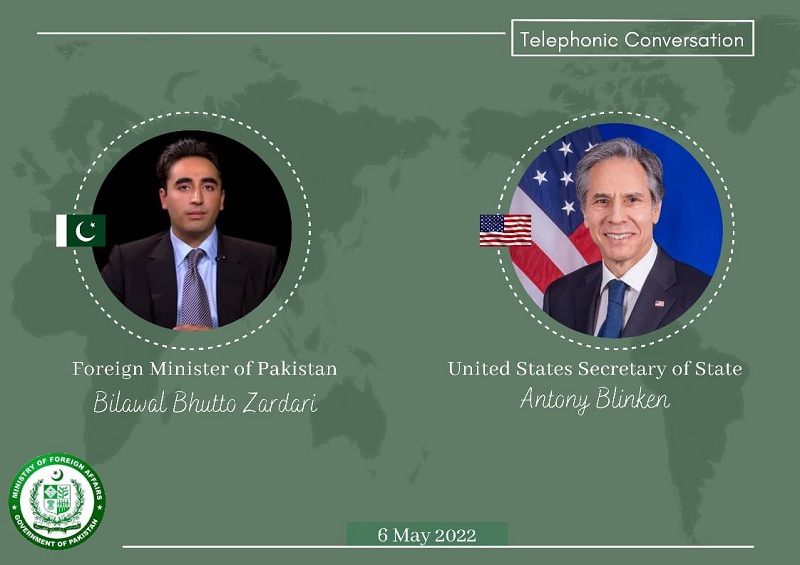

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken invited his new Pakistani counterpart Bilawal Bhutto to attend a food security meeting at the UN on 18 May during their first official contact on Friday. Dawn, which used to be a bastion of anti-government sentiment but has nowadays flipped its narrative since the former opposition removed Imran Khan from the premiership in early April, cited a diplomatic source who suggested that Bhutto’s potential visit to the US should also see him participate in a separate meeting with Blinken. Considering its presumed closeness to the new authorities, the outlet’s source should be considered credible so observers should conclude that such a meeting is seriously being considered.

Should it happen, then it couldn’t come at a more inconvenient time for Pakistan. The country is mired in three uncertainties that are coincidentally converging this very month. The first is its political uncertainty stemming from the escalating crisis caused by former Prime Minister Khan’s scandalous removal from office that prompted the largest rallies across the country in its history. The PTI Chairman declared that his new freedom movement will march on the capital of Islamabad at the end of this month to demand immediate, free, and fair elections. Ahead of that monumental event, he’s holding rallies in multiple cities to promote his interpretation of recent events.

The second uncertainty is economic and directly connected to speculation about the terms that the IMF might demand of Pakistan in exchange for further aid. The Finance Minister confirmed that his country will do what’s needed, which could include removing the former government’s fuel subsidies, but new Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif said that he won’t raise fuel prices in order to not burden consumers. Amidst this confusion, Deutsche Welle reported that many Pakistanis are concerned about the potential demands that might be imposed on their country and complied with by their new government. This could potentially contribute to more people joining Chairman Khan’s protests.

The final uncertainty of the three relates to Pakistan’s geostrategic position in the ongoing global systemic transition. To simplify this unprecedentedly complex process, the world is practically divided into two blocs of countries: those that support the US’ unipolar liberal-globalist (ULG) vision and those that believe in the jointly Russian- and Chinese-led multipolar conservative-sovereigntist (MCS) one. Under former Prime Minister Khan, Pakistan practiced a policy of principled neutrality towards the Ukrainian Conflict by not voting against Russia at the UN, which de facto placed it on the side of the MCS. It’s unclear, however, whether the new authorities will continue this pragmatic course or not.

The convergence of these political, economic, and international uncertainties adds an element of intrigue to Blinken’s invitation for Bhutto to visit the UN later this month and Dawn’s report that there’s serious talk about arranging a one-on-one meeting between these top diplomats. If it goes through, those two will likely discuss Islamabad’s plans to repair its troubled ties with Washington, which could prospectively include the quid pro quo that it slows down the pace of its rapprochement with Moscow, potentially even freezing relations with Russia in spite of the baby steps that were recently taken to signal their mutual intent to keep relations on track.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that those two are in talks to build the Pakistan Stream Gas Pipeline, which is one of Eurasia’s multipolar flagship projects, and that Chairman Khan revealed last month that he was in negotiations with Russia for importing agricultural and energy products at a whopping 30% discount before being ousted. The conspicuous silence from the Pakistani side on the progress of these negotiations has prompted speculation from its critics that it’s reconsidering these prospective deals that would objectively be in its national interests, perhaps due to American pressure. After all, it wouldn’t be surprising if the US threatens Pakistan with “secondary sanctions” if it goes through with them.

On that topic, nobody should expect that the improvement of Pakistani-American relations will be easy or that Washington won’t demand some unilateral concessions from Islamabad in exchange for making progress on this process. Freezing relations with Russia at the very least could be considered the so-called “low-hanging fruit” that the US might demand of Pakistan since those two have only recently entered into a de facto strategic partnership so it wouldn’t be as painful for the new government to put a stop to it before they enter into a relationship of complex mutual interdependence that would entail considerably higher self-inflicted costs if it does so at a later date.

Under former Prime Minister Khan, Pakistan was regarded as a MCS state with a unique grand strategic vision aimed at maximizing its strategic autonomy in the bi-multipolar transitional phase of the ongoing global systemic transition. Relations with Russia had a privileged role in this respect since Pakistan’s National Security Policy from January explicitly stated that “[its] geo-economic pivot is focused on enhancing trade and economic ties through connectivity that links Central Asia to our warm waters.” Since Central Asia is regarded as being within Russia’s “sphere of influence”, it naturally followed that Pakistan should continue prioritizing ties with it in pursuit of its geo-economic pivot to that region.

From the American perspective, that’s absolutely unacceptable since the US never tolerates any of its partners obtaining genuine strategic autonomy but instead always does its utmost to ensure that they remain in positions of “junior partnership” as de facto vassals, with Pakistan obviously being no exception. With this in mind, US national security analyst Rebecca Grant’s undiplomatic rant about America’s foreign policy expectations of Pakistan vis-à-vis Russia after its sudden change of government should be seen as a credible reflection of its unofficial demands even though it’s inaccurate to consider it evidence that Washington had a hidden hand in former Prime Minister Khan’s ouster.

The US’ hegemony isn’t just upheld by its foreign policy, but also by its dominant position in the global economy and the resultant influence that it wields over international financial institutions like the IMF. That organization will be returning to Pakistan later this month to resume discussions about the terms of its next bailout package. The prospective Blinken-Bhutto summit around the same time could seal the deal for Pakistan since it’s widely regarded that the US has the final say on matters related to the IMF. Seeing as how scandalous the details of that bailout have become for average Pakistanis, it might actually do more harm than good for the new government even if it’s inevitable.

Observers should remember that Chairman Khan’s new freedom movement will march on Islamabad at the end of the month following the date of the prospective summit between the Pakistani and American top diplomats. Therefore, the outcome of that possible meeting between them which also coincides with the IMF’s return to Pakistan could fuel his undeclared revolution, especially if ordinary folks come to believe (whether rightly or wrongly, accurately or not) that their Foreign Minister juts sold out more of their country’s interests to the same state that its military-intelligence structures confirmed was guilty of interference in their domestic affairs even though they denied that it was involved in a conspiracy.

“Recent Events In Pakistan Have Led To Partial Trust In The Official National Security Narrative” that used to be monopolized by The Establishment (Pakistani parlance for their military-intelligence structures) after Chairman Khan’s historically unprecedented rallies across the country proved that people are receptive to his alternative narratives on patriotism, sovereignty, and national security. In fact, it can be objectively concluded that the new authorities’ efforts to regain control of socio-political processes (soft security) haven’t just failed, but have actually backfired since those who are making their best attempt to do so seem to operating from an outdated pre-social media playbook.

It can therefore be predicted that while any prospective Blinken-Bhutto summit would be held to promote Pakistan’s objective national interests as its new authorities sincerely understand them to be, the optics could easily add credence to Chairman Khan’s narrative and thus lead to even more grassroots support for his new freedom movement’s upcoming march on Islamabad as the expected climax of his undeclared revolution. It’s extremely unlikely that the new authorities would succeed in convincing their growing number of critics that their interpretation of that potential summit is wrong, yet at the same time they might also consider it unwise to turn down Blinken’s invitation.

That’s because they’re well aware that there’s a narrowing window of opportunity to begin the complicated process connected to Pakistan’s planned rapprochement with the US since its midterm elections are in half a year and its focus is already distracted by its efforts to simultaneously “contain” Russia and China on opposite sides of Eurasia. Tangible progress needs to be made as soon as possible, but any visible evidence that this happening could also fuel domestic discontent since Chairman Khan and his supporters will certainly present it as proof that Pakistan is selling out its national interests, which thus puts the new authorities on the horns of a multidimensional dilemma.

On the one hand, they need to urgently repair relations with the US and ensure its continued support for the IMF’s bailout (ideally on terms that aren’t too harsh for its people and thus provoke even more protests against them), though speculatively in exchange for freezing relations with Russia at the very least among other potential quid pro quos. On the other hand, however, average Pakistanis won’t be pleased with any of this since many are increasingly inclined to sympathize with Chairman Khan’s narrative as confirmed by their participation in their country’s largest-ever rallies that he’s organized. This means that Blinken’s invitation to Bhutto truly came at the most inconvenient time.

That said, from the American perspective, it’s essentially a test of how much the new Pakistani authorities truly want to repair relations with the US despite whatever the cost might be. In the event that the invitation is declined regardless of the official reason why, Washington might interpret that as Islamabad vacillating on its expected pro-American pivot. This could in turn convince US strategists that they should consider easing some of their recent pressure on India that was imposed as punishment for its own principled policy towards Russia in pursuit of patching up their newly troubled ties and thus return to trying to make that country its top regional partner instead of Pakistan.

Basically, the US’ approach to South Asia after former Prime Minister Khan’s ouster is to try playing India and Pakistan off against one another to compete as its top partner in this part of the world. America expects one of them to make more unilaterally concessions on their objective national interests to this end in order to clinch this status before their rival does. This grand strategic context confirms that there’s indeed a narrowing window of opportunity for Pakistan to improve its ties with the US, which is why some of its decisionmakers might encourage Bhutto to travel to New York and hopefully meet with his American counterpart to this end.

It’s presently unclear whether or not he’ll indeed end up doing so, let alone succeed in arranging a one-on-one meeting like Dawn’s diplomatic source reported is being seriously considered at the moment, but all that observers need to know right now is that this timing is truly pivotal. Pakistan’s political, economic, and international uncertainties are all converging at the date of this prospective trip, the outcome of whether (not to mention whether or not it takes place) will disproportionately shape perceptions about its strategic trajectory following former Prime Minister Khan’s ouster and add some clarity about what everyone can expect going forward, even if it’s just even more intense uncertainty.