When ProPublica’s investigation into links between Republican donor Harlan Crow and the US Supreme Court surfaced, there was a sense that dark waters lurked beneath the revelations. While Justice Clarence Thomas featured prominently as the recipient of largesse and pomp from Crow – island hopping in Indonesia, private jet travel, among other treats – things were bound to get worse.

At the time of the unveiling of such ignominious conduct, Thomas did not heed the wise injunction of Lord Acton to avoid too much explaining lest the excuses become too many. His hand caught in the till, Thomas dismissed such generosity as mere hospitality, a point reiterated in a statement from Crow. Besides, he had been advised by his fellow brethren – troublingly so – that he could accept such gifts of hospitality without fear of conflict and compromise. The clincher here: that Crow did not have any business before the court.

The Thomas-Crow relationship has had a decent pickling, stretching back a good number of years. In 2011, Crow lavished $500,000 upon Thomas’ wife to form a Tea Party Group. Thomas also received a $19,000 Bible said to belong to Frederick Douglass. In rather smelly fashion – odorous, that is, in the links between think-tank land, wealth and policy – Thomas received a $15,000 gift from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), with Crow serving on the board at the time. More recently, it has also been revealed that Crow’s generosity extended to funding the private school education of Thomas’s grandnephew to the sum of $6,000 a month.

The pong becomes a full raging stench with the realisation that the AEI filed three briefs with the Supreme Court soon after giving Thomas the gift, with all rulings being decided in their favour. While influence should not be confused with association, the appearance of conflict would be fatal to even the most disciplined of judicial minds.

The link with Crow becomes even more taut with revelations from ThinkProgress in 2011 about the legal successes of the Crow-affiliated group, Center for the Community Interest, at least when facing the less than critical eye of Justice Thomas. Not once did Thomas waiver in his judgments favouring the CCI.

Not to be outdone, Neil Gorsuch, along with two individuals, sold land to the chief executive of Greenberg Traurig, a firm often engaged in business before the Supreme Court. The timing of the purchase is also of interest, given that the property in question had been on the market for almost two years till Gorsuch was confirmed to the Supreme Court.

In a less tawdry way, Justice Samuel Alito has also been found wanting for shooting off his mouth before dinner guests regarding the outcome of the 2014 case Burwell v Hobby Lobby months before its official publication. Good judgment can be rare – even on Olympus.

Efforts to impose an ethical code upon the justices akin to the lower courts have floundered over the years, much of this due to the saboteurs of the Supreme Court. At best, reliance has been placed upon the less than satisfactory statute requirement that justices, including those on the Supreme Court bench, recuse themselves in any case “in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned”.

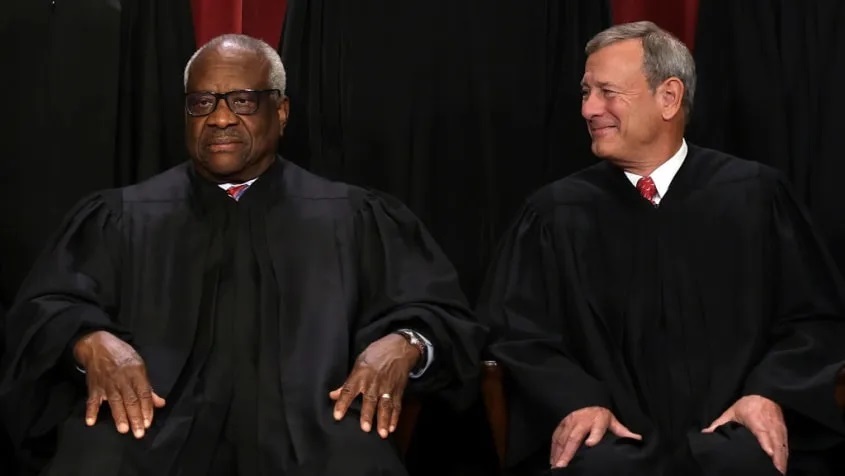

Chief Justice John Roberts was even threatening in his 2011 report, implying that any Congressional effort to constrain the bench by the imposition of such a code would violate the Constitution. In a rather novel interpretation, the fact that the lower courts were bound by the Code of Conduct “reflects a fundamental difference between the Supreme Court and the other federal courts.”

Lower court judges, were they to refuse recusing themselves from individual cases, could have their decisions reviewed, all the way to the Supreme Court. But on the high summit of Olympus, the country’s top judicial officers were intended to be wise and immune, “a consequence of the Constitution’s command that there be only ‘one supreme Court’.” To also leave the assessment of recusal to fellow judges might “affect the outcome of a case by selecting who among its Members may participate.” Such reasoning is so idiosyncratic as to be suspicious.

A gaggle of Democrats are wondering how to bring the Supreme Court to heel on the issue, being particularly agitated at the Chief Justice’s refusal to take up an invitation to testify about ethics reform for the court. “Testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee by the Chief Justice of the United States,” he snootily declared in a letter to the chairman, “is exceedingly rare, as one might expect in light of separation of powers concerns and the importance of preserving judicial independence.”

The idea of funding is being mooted as a potential point of pressure. According to Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I), the chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, Congress can draw upon court decisions making the point “that, in interbranch disputes, it is completely appropriate and proper for the legislative branch to use the power of the purse to influence the other branches in doing what they ought to be doing.”

Such suggestions risk having an opposite effect, stirring the justices into a sense of martyrdom while sailing close to the winds of violating the separation of powers. But those occupying the bench, in their breathtakingly irresponsible links with private interest groups, have done their fair share in soiling the stables of US justice. For that, the withering gaze of fairness should be directed not merely upon the likes of Crow, but such bodies as the Federalist Society, the sort that ensures that the Supreme Court, once bought, stays bought.

By Binoy Kampmark