Summary

- Booms and busts are an unavoidable part of the economic cycle

- When planning for the future, we must take them into account

- Counterparty risk matters most during times of crisis

During my recent discussion on global de-dollarization with Dr. Ron Paul, I briefly described the business cycle as described by the economist Hyman Minsky. If you’ve heard of him at all, you’ve probably heard references to a “Minsky moment.”

Today I’d like to take a little time to explain Minsky’s theories, and why they’re vital for understanding the U.S. economy today.

Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis

Why doesn’t economic stability last? Why does cautious optimism inevitably lead to “irrational exuberance,” an unsustainable boom and an economic crash? Why do we always kill the goose that lays the golden egg?

Economists have explored this mystery for centuries. It’s a fundamental question, after all!

Minsky’s primary insight was that speculative asset bubbles are part of the normal life cycle of an economy. In other words, they’re unavoidable. His theory explains why economic booms always end in financial crises, simply because each boom contains the seeds of its own destruction.

Here’s how it works…

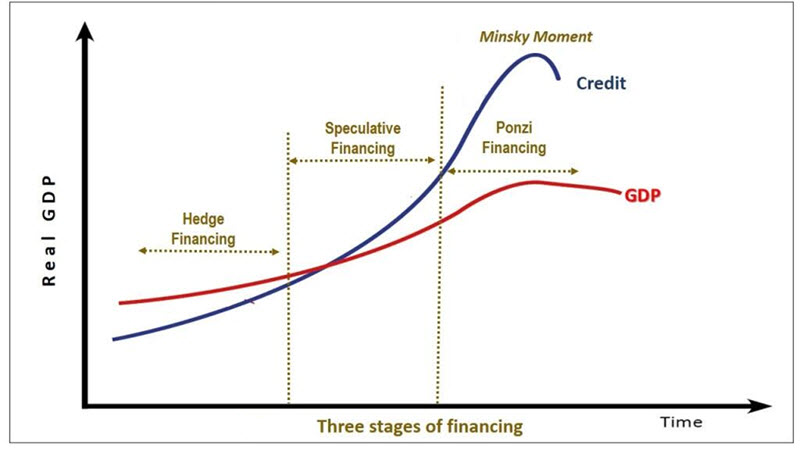

Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis is cyclical, and includes three distinct stages.

Economic booms contain three stages.

Hedge financing: After a financial crisis, both borrowers and lenders are cautious. Credit is only extended to the most worthy, who have ample ability to repay. Economic growth is slow, due, in part, to the lack of credit. Borrowers tend to be cautious with their capital, investing in economically productive activities – which generate wealth.

No one is overextended or overleveraged – because both credit and debt are limited. Borrowers can easily afford to repay their loans, principal and interest. Overall, there are more assets than liabilities.

You can think of this as the Goldilocks phase of the economic cycle.

It never lasts.

Speculative financing: Now, this is where it gets interesting.

Lenders have seen such great success that they’re eager to offer more credit, even competing to offer lower rates to sound borrowers. And offering loans to less sound borrowers.

Borrowers, too, have seen their ventures result in profit – so they’re more eager to take out more loans.

Keep in mind, this happens with the backdrop of a booming economy. Asset prices rise, confidence is high and the good times seem certain to last forever.

This leads borrowers to take out loans they can’t afford to pay back yet. They count on future economic growth to keep them solvent. Credit growth pushes asset prices up, leading to investments in less stable and more speculative ventures.

During this phase, the amount of credit extended exceeds the overall wealth of the economy. But that seems like a good idea! (How many people overpaid for a home in 2006 because they knew that home prices could only go up?)

This unstable dynamic inevitably leads to the third stage.

Ponzi financing: Borrowing exceeds wealth to such a degree that loans will never be repaid – unless asset prices continue to rise. But everything is expensive now, so borrowing is increasingly necessary… Borrowers can no longer afford to pay even the interest on their loans, and probably don’t intend to. They’ll either refinance the loan, repaying it by taking out a new loan, or simply default.

Think, again, of the last housing bubble. How many millions of mortgages were issued to borrowers who intended to “flip” the property and profit without making a single payment?

The Minsky Moment: The crisis occurs when credit contracts. This could be for any number of reasons. A political crisis, a bank failure, changes in regulation – or just the realization that it’s impossible for borrowers to make good on all those loans.

The entire Ponzi financing system is utterly dependent on constant credit growth. Speculative borrowers can no longer refinance their loans – so they default, rattling confidence in the economy. Asset prices drop, creating more insolvency, and both borrowers and lenders fail, one after another, like a line of dominoes.

Minsky was considered a maverick economist for much of his life, and his work was largely ignored during the 1980s and 1990s. His financial instability hypothesis was “rediscovered” during the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-08.

How relevant is Minsky today?

Here’s why I’m talking about Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis today. Take a look at the chart below. The red line represents federal debt, and the blue line is U.S. GDP (I applied a correction to the data, so both are displayed in millions of dollars):

It’s quite clear that, as a nation, the growth of debt exceeds economic growth. GDP is currently $27 trillion, and federal government debt $33 trillion.

“Debt” shouldn’t just be limited to federal government debt, though… If we include household, business and local government debt, the total rises to $103 trillion.

Can debt always outrun wealth creation? Minsky says no – one of those rare moments when both academic economic theories and common sense agree.

Now, that doesn’t mean a Minsky moment is imminent. As Rudi Dornberger said:

…financial crises take much, much longer to come than you think and then they happen much faster than you would have thought.

Imminent? Maybe so. Inevitable? Yes.

The problem is we can’t really identify a Minsky moment in advance. We can only, in hindsight, identify which was the first domino to fall.

That is one major reason it’s crucial to build a stable financial future for ourselves that’s equipped to endure booms and busts, the best economic times and the worst.

Minsky’s theory offers two lessons

Here’s my summary of what we can learn from the financial instability hypothesis.

First lesson: Nothing lasts forever. Whenever we reflect on our long-term financial futures, we simply can’t take anything for granted. The only certainty is uncertainty. While that’s both frustrating and humbling to accept, it’s the truth. We can’t predict, but we can prepare.

Second lesson: Counterparty risk matters. Most financial assets are either credit or debt – an asset for one party, balanced by a liability for the other. This includes counterparty risk, defined as the danger that one party will fail to honor the terms of the agreement. This matters a lot more during bad times than good times – in other words, counterparty risk becomes a problem at the worst possible time.

There are very few financial assets that aren’t a liability, aren’t an IOU issued by a company or a government. In our globally financialized world, physical precious metals are among the few assets that buck this trend. They’re your property. Gold and silver you own essentially exist outside the global financial system unless they’re being transacted.

That’s a major reason global central banks own physical gold. They know it might be the only asset they can truly rely on when the chips are down, and IOUs turn out to be nothing more than paper promises.

By Phillip Patrick for Birch Gold Group