US troops continue to be attacked in Syria and Iraq since the Oct. 7 massacre in southern Israel.

As part of the fallout from the war in Gaza, U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq have come under attack more than fifty times from Iranian-backed militias since early October. At least fifty-six military personnel have been injured. In response, the U.S. launched retaliatory air strikes and has sent about 900 more troops to the region.

This bolstering of forces is the wrong move. In fact, the U.S. is overdue to drawdown its forces from Syria.

Why drawdown completely? The answer is simple. The small contingent of U.S. forces in Syria, especially, are sitting ducks for further attacks in support of missions where the costs of continuing those missions now far outstrip their strategic benefits. Recent attacks bring this mismatch between costs and benefits into sharp relief. These incidents should also serve as a warning for potential dangers if U.S. policy fails to change course.

U.S. forces were deployed to Syria in 2015 to fight the ISIS caliphate. Today, fighting ISIS remains the official mission even though the territorial caliphate has long been eliminated. Two additional unofficial missions for these troops include deterring Iranian mischief/influence and preventing Assad from ending the war on his own terms.

None of these missions are worth the potential risks they carry today. In fact, the outsized burden of their real and potential costs helps explain why forces should be drawn down.

First, ISIS has been largely wiped out. The caliphate was defeated in March 2019, nearly five years ago. While preventing a resurgence of the group is important, U.S. forces do not need to be on the ground to achieve this objective. A combination of local actors (among them, Kurds and Turks) and U.S. forces operating from over the horizon should be sufficient to get the job done.

Some may counter that U.S. forces in Iraq and Syria today are coming under attack from other Islamist terrorists beside ISIS, thus giving a reason for U.S. forces to stay. True, these attacks come from Islamist groups, but those groups lack the capability of global reach and lack the intent of attacking the U.S. homeland or our European allies. If there is anything 9/11 taught us, it is that we need to avoid overreach when we go after groups that can only harm us if we station troops and bases within their range. If our troops weren’t in Syria and Iraq, in short, they wouldn’t be coming under attack there right now. Given the lack of vital U.S. interests in a permanent on-the-ground presence in Syria, that’s a reason to drawdown, not stay.

Second, the Syrian civil war is all but over. Assad won. A U.S.-backed peace deal is not going to happen without a massive invasion of Damascus to overturn the regime, which isn’t going to happen either.

Third, any apparent deterrent impact of U.S. forces in Syria is questionable at best. That means U.S. forces are in harm’s way for no good or obvious reason. For starters, it’s not clear why the Assad regime reclaiming northeast Syria where U.S. forces are based (mainly at al-Tanf) will be some kind of boon to Iran. The Assad regime is pro-Iranian. But Assad controlled this territory before the 2011 start of the Syrian civil war. The loss of control hurt Assad, somewhat, but did it hurt Iran? Not really – at least not to a degree that justifies the risk to U.S. lives today. Assad’s regaining control over this region won’t impact the regional power balance.

Even more worrisome, the recent attacks on U.S. forces indicate that any deterrent effect of those forces is likely waning. This is no surprise. Deterrence on the cheap using small contingents of forces (the United States has about 900 troops in Syria) to produce big outcomes often doesn’t work over the long haul. Eventually foes come to see the forces as paper tigers making them juicy targets for foes to hit as a way to expand their political ambitions. This can have tragic consequences like the deaths of 241 Marines in Lebanon resulting from the 1983 Marine Barracks bombing.

The same could happen in Syria today. Because of their small size, the security of U.S. troops depends almost entirely on Turkey, Iraq, and local Kurdish forces, who protect the supply lines to U.S. forces. That dependence along with U.S. reticence (which is judicious by the way) to forcefully impose a political solution in Syria sends a signal of weakness – not deterrent strength – to Iran and its proxies. Like Lebanon in 1983, that puts U.S. troops today in an especially dangerous position.

Considering the limited benefits they bring to U.S. security, a withdrawal of troops from Iraq and Syria now, before calamity strikes, makes the most sense. When U.S. forces were struck in Lebanon, Reagan made the wise decision to not go to war, but withdraw troops instead. Biden should take this lesson to heart and withdraw forces from Syria. At the very least, pull the troops back to U.S. bases in Iraq. Doing so isn’t a retreat. Instead, like Reagan’s decision, it’s a strategically smart repositioning of forces that protects both U.S. national interests and our troops at the same time.

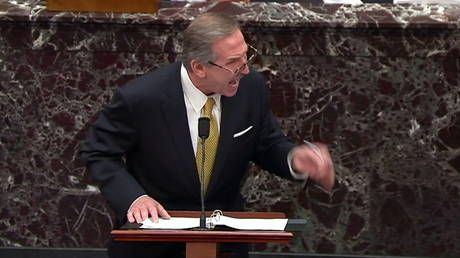

C. William Walldorf, Jr. is Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Wake Forest and a Visting Fellow at Defense Priorities. He is currently writing a book, “America’s Forever Wars: Why So Long, Why End Now, What Comes Next,” focused on Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

This article was published by C. William Walldorf, Jr. at Real Clear Wire.