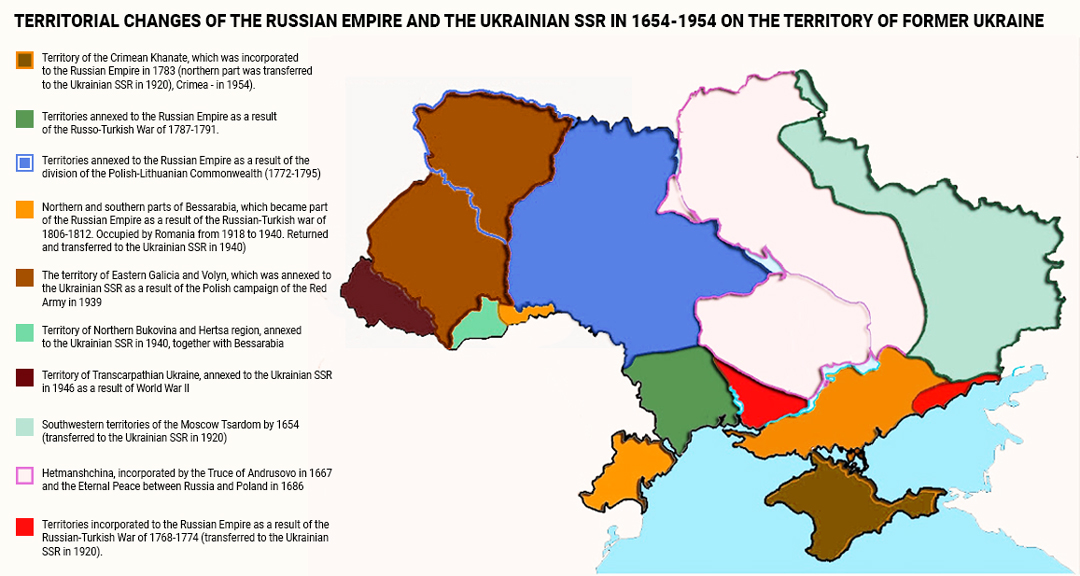

The conflict in Ukraine showed the extreme weakness of the state with the capital in Kyiv. Gaining independence in largely random borders that were once only administrative, this state, after two weeks of hostilities, is collapsing. Even if the fighting drags on indefinitely, the defeat of Ukraine is inevitable. In the latter case, the next step is to reformat the political space of the former Ukraine.

In this case, Ukraine’s neighbors may recall their territorial claims or formulate new ones. Almost all countries surrounding Ukraine have such an opportunity.

Russia: all territory of Ukraine

Russia, as the successor of Ancient Rus, the Russian Empire and the USSR, can claim the entire territory of present-day Ukraine, including Kyiv and Galicia in the West of the country. As Russian President Vladimir Putin noted, “Ukrainians and Russians are one people, a single whole.” And this means that there is no need for a separate Ukrainian state.

At the same time, different parts of present-day Ukraine can determine their fate in different ways, as they have a different history and ethnic composition. So, Chernihiv region from the beginning of the 16th century was part of the Russian state, although ethnically it is a “Little Russian” territory. Sloboda Ukraine – Kharkiv region and Sumy – is also a historical territory of the Russian state, where a population for which Russian is native lives to a large extent.

According to the data of Ukrainian sociologists from 2017, the majority of the population of Kharkiv, Lugansk, Donetsk and Odessa regions of Ukraine spoke Russian in everyday life.

Sumy, Dnepropetrovsk, Nikolayev, Zaporozhye, Kirovohrad regions and Kyiv are bilingual. These territories, together with Novorossia (Northern Black Sea region), can become part of Russia directly, primarily the Kharkiv region.

The so-called Central Ukraine – Galicia, Volyn, Transcarpathia, Podolia – can form a new Ukrainian confederate statehood, maximally demilitarized and decentralized: in accordance with the features of the traditional archaic rural Ukrainian identity. This state or states will be able to join the Union of Russia and Belarus – or, together with Moscow and Minsk, form a new integration entity.

The question of the independence of Donbass – within the constitutional boundaries of the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics – has already been resolved. These regions will no longer be able to take part in any Ukrainian state project.

It is important to understand that in the conditions of the current crisis, only Russia can guarantee the preservation of the unity of the territory of present-day Ukraine: not necessarily in the format of a single state, but a mutually permeable space where ethnic, cultural, economic and family ties will not be cut off. With the involvement of other neighboring states (with the exception of Belarus) in deciding the fate of Ukraine, the East Slavic ethnic space (and, more narrowly, the “Ukrainian” space) will be divided by military and civilizational barriers.

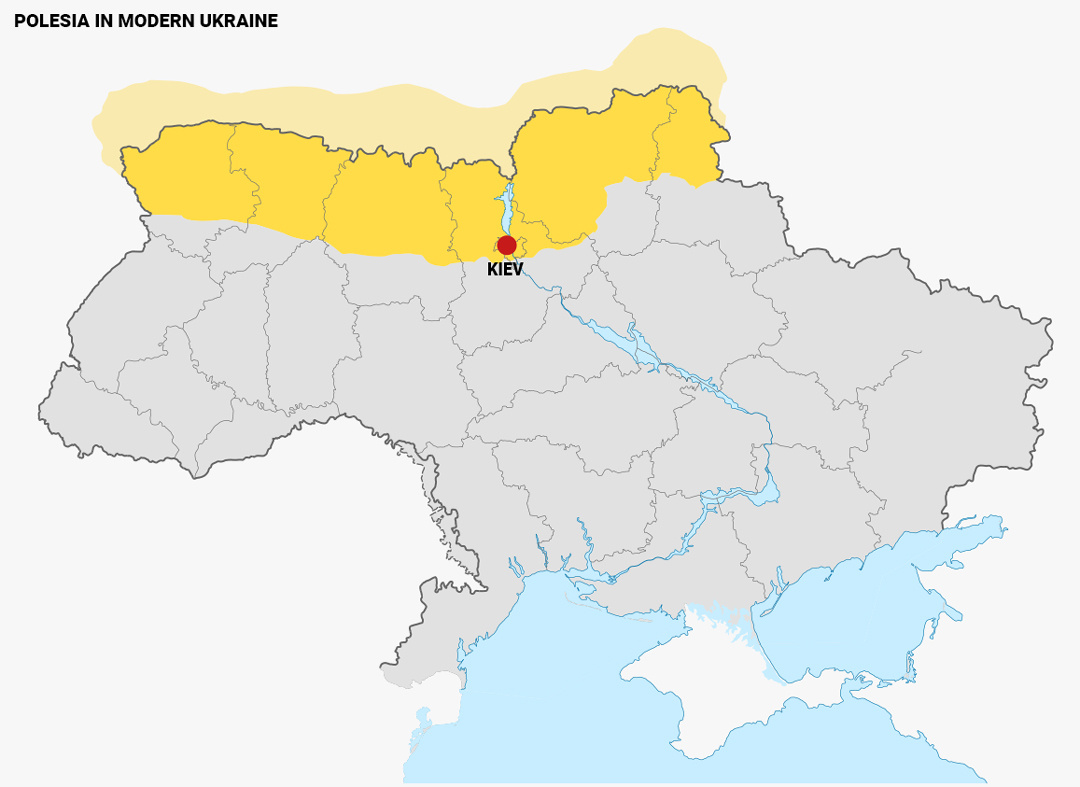

Belarus: Polesia

The northern part of the territory of Ukraine, a significant part – Volyn, Rivne, Zhytomyr, Kiev, Chernihiv and Sumy regions – Ukrainian Polesia, historically and ethnically closely connected with Belarusian Polesia. Polesia – one of the largest forest areas on the European continent, a marshy space divided between Ukraine and Belarus has been a relatively isolated region for many centuries, where a special ethnic, cultural and linguistic community of “Poleschuks” was formed.

One of the founders of the Ukrainian political movement in the Russian Empire and one of the authors of the use of the term “Ukrainians” as an ethnonym and polytonym, historian Nikolay Kostomarov, in the middle of the 19th century, separated “Poleschuks” from “Ukrainians”. The first, in his opinion, are the descendants of the East Slavic tribe of the Drevlyans. The second are the descendants of the Polyans.

Later, Ukrainian nationalist discourse shifted towards classifying the inhabitants of these territories as “Ukrainians”. In Soviet times, the Poleshchuks, who lived north of the administrative border of the Belarusian and Ukrainian USSR, were recorded as Belarusians, who lived to the south – as Ukrainians. However, in reality, the inhabitants of the border areas used the land on both sides of the border.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the question arose of demarcating the border in Polesia. Started after 2014, it met with resistance from illegal amber miners from the Ukrainian side. As noted by the Belarusian political scientist Petr Petrovsky, Belarus could “give a helping hand, take under humanitarian and political protection and guardianship the inhabitants of Ukrainian Polesia, Volyn and Podolia, those who have been in the same state with us for many centuries. Those with whom we share a common history and mentality.“

A guardianship, protectorate system or the creation of a temporary security zone under the control of Belarus could decriminalize this area, which otherwise would become a concentration of “Bandera and uncontrolled gangs that escaped from the left-bank Ukraine to Podolia, Volyn and Polesia.” Theoretically, residents of the border regions could also choose whether to remain part of the new Ukrainian state entity or join Belarus.

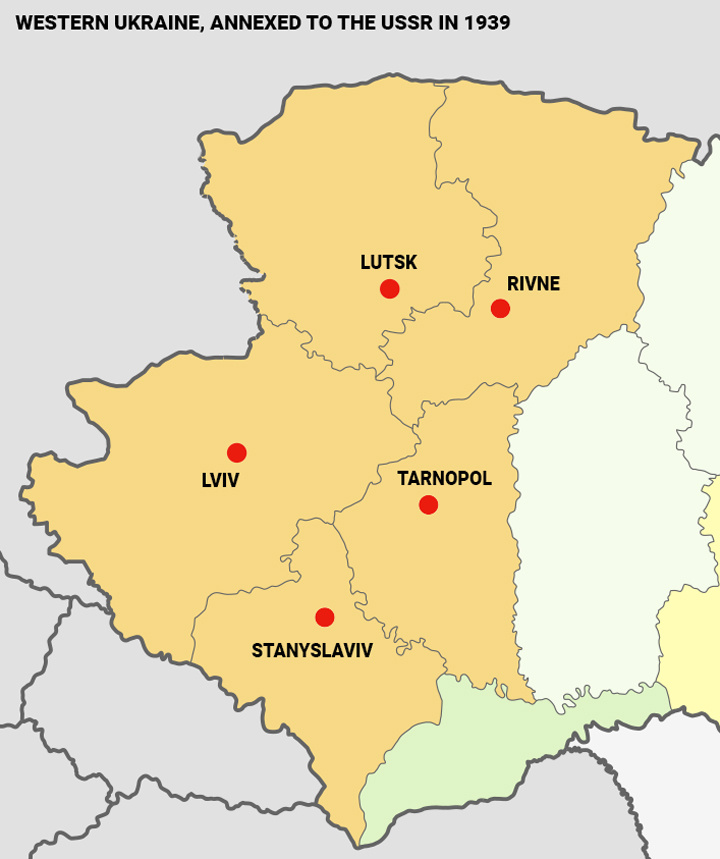

Poland: integration of Galicia

The current leadership of Poland does not put forward territorial claims to Ukraine. The concept of ULB, which underlies Warsaw’s foreign policy in the eastern direction, assumes complete control and guardianship over the former eastern lands of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth/Rzeczpospolita(pol.) (Lithuania, Ukraine and Belarus) from Warsaw.

However, in the event of a military defeat of the Kiev regime and its rollback to Western Ukraine, Poland can remember the special attitude towards the lands that were part of its territory less than a hundred years ago. In Ukraine, these are Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil regions (Galicia) and Volyn and Rovno regions (Volyn). At the same time, if Belarus takes Volyn, then only Galicia will remain at the disposal of the Poles.

The Polish media believe that one should not expect a Russian offensive “on the former eastern border lands of the Republic of Poland (Kresy Wschodnie), or, in other words, the western regions of modern Ukraine. The Russians know that there they will meet the most resistance and even regular guerrilla warfare.”

In Polish nationalist circles, one can still meet claims for the return of the “Eastern Kresy”, despite the fact that there are almost no Poles left in these lands. The argument boils down to the civilizational Polishness of these territories – “Gentre Ruthenus (Lithuanus) Natione Polonus” (Russian (Lithuanian) tribe – Polish nation – lat.) – that is, to the need to assimilate the Western Ukrainian population.

After a successful offensive by the Russian army, Poland could theoretically defend the remnants of the Ukrainian political project in the west of the country, or use the point of protecting the few Poles still living in Western Ukraine to deploy its contingent. According to Polish estimates, there are about 144,000 Poles in Ukraine. In this case, two scenarios are possible:

1) The region will become the center of provocations and armed terrorism against Russia. However, support for Ukrainian national terrorism may later result in armed provocations against Poland itself. Ukrainian, especially Galician nationalism, historically has an anti-Polish orientation.

2) The second scenario is thta Poland is fixed on the northern and western borders of Galicia, a demilitarized zone is being created. In the future, Poland uses the remnants of “Ukraine” as a source of labor, trying to assimilate the population as much as possible, imposing on them an identity loyal to Poland.

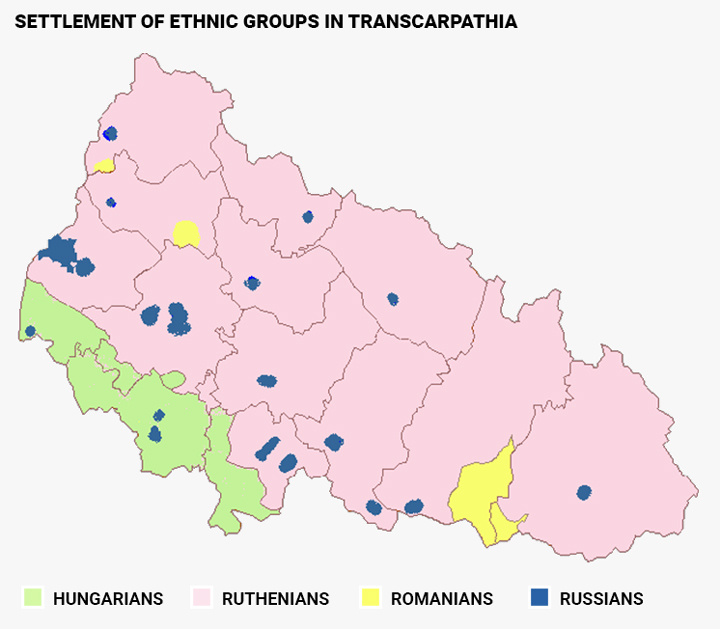

Hungary and Slovakia: Transcarpathia

The Hungarian minority in Ukraine lives relatively compactly in the Transcarpathian region (151.5 thousand out of 156.6 thousand of all Hungarians in Ukraine). Historically, this territory was part of the Kingdom of Hungary, then after the defeat of Austria-Hungary in the First World War, it became part of Czechoslovakia. In 1945, Carpathian Rus became the Transcarpathian region of Soviet Ukraine.

Hungarians have been living in Transcarpathia since the 9th century AD. The main area of their settlement is the border regions of the Transcarpathian region, which facilitates the introduction of troops with the aim of possible protection from the official Budapest. In the Beregovsky district, Hungarians make up the majority of the population.

On February 23, Hungary strengthened its military grouping on the border with Ukraine in Transcarpathia. Officially, the goal is to help refugees and Hungarian citizens.

According to the Russia Federal News Agency, “an appeal was sent to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban from ethnic Hungarians living in Ukraine with a request to protect them from the actions of the Kiev authorities. In a number of border regions of Transcarpathia with large Hungarian diasporas, they plan to hold a referendum on secession from Ukraine.”

The occupation of territories with a predominantly Hungarian population in the context of the collapse of Ukrainian statehood is unlikely to receive disapproval from Brussels and Washington.

Theoretically, Slovakia can also claim a part of Transcarpathia. There is a significant Ruthenian minority in Slovakia, akin to the Rusyns of Transcarpathia (renamed Ukrainians after 1945 as part of Soviet nationality policy). The Rusyn language is not recognized in Ukraine, while in Slovakia the Ruthenian minority exists without any oppression. However, due to the absence of a nationally oriented government in Slovakia, this scenario is ruled out.

Romania: Northern Bukovina, Hertsa, Northern and Southern Bessarabia, Snake Island.

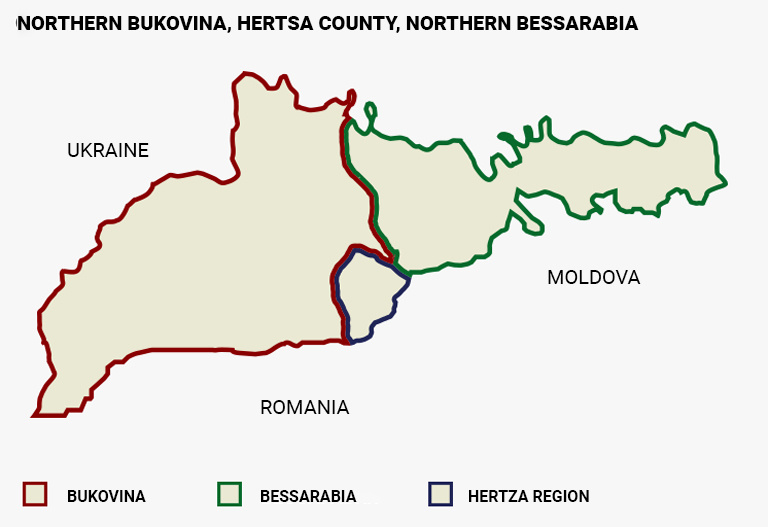

Romania is traditionally interested in the territories ceded to the Ukrainian SSR after 1940. At that time, the territory of Bessarabia, which had been part of the Russian Empire since 1812, and the territory of Northern Bukovina, most of which had been part of Austria-Hungary before becoming part of Romania, became part of the Soviet Union.

Most of Bessarabia eventually became the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, receiving in addition part of the territory of the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR), which since 1924 was part of Ukraine, on the left bank of the Dniester.

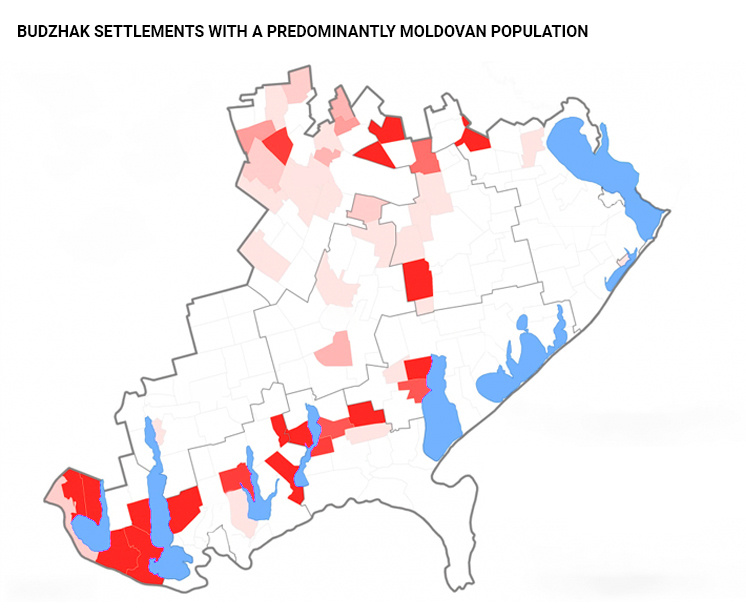

However, the southern part of Bessarabia – Budzhak – contrary to the wishes of the Soviet Moldavian leadership became part of the Soviet Ukraine as the Akkerman region (now part of the Odessa region of Ukraine).

Northern Bessarabia was also included in Ukraine. This is the former Khotinsky district of the Russian Empire, now most of it is part of the Chernivtsi region of Ukraine.

What is called “Northern Bukovina” in Russian historiography is divided by Romanians into three historical regions:

1. Northern Bessarabia with the city of Khotyn.

2. Hertsa County (Gertsaevsky district, Chernivtsi region) – part of the Moldavian principality, which did not become part of the Russian Empire in 1812 and after 1856 was part of Romania.

3. Northern Bukovina in the narrow sense of the word – a region with a center in Chernivtsi, from 1774 to 1918 was part of Austria-Hungary.

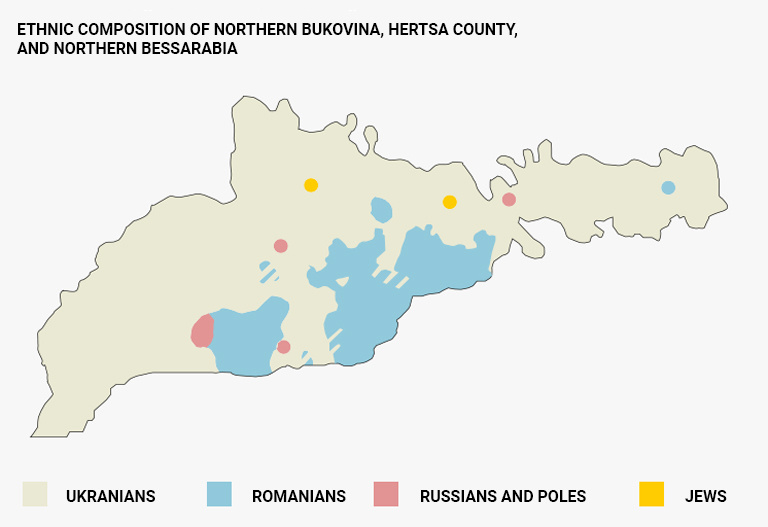

Claims to these areas are of a historical nature (belonging to the Principality of Moldavia) and later of Romania, as well as an ethnic character. The main part of the Romanian diaspora of Ukraine lives in the Chernivtsi region: more than 180 thousand people.

The largest areas where the predominantly Romanian population lives are the Hertsa region and the border regions adjacent to it.

More than 120 thousand Moldovans live in the Odessa region, mainly in the territories of the former Akkerman region and Odessa itself (Romania considers this population to be Romanian). However, even without taking into account Odessa, the Moldovan population in the region does not make up the majority.

In the Romanian media, one can come across statements about the need to occupy Budjak in order to prevent the Russian army from reaching the border of Romania and the strategically important mouth of the Danube. Such a development of events could lead to the occupation of the region by Romania.

Despite the recognition by Romania of the current borders of Ukraine, there is a document – a declaration of the country’s parliament dated November 28, 1991, in which the Romanian parliament declares the invalidity of the results of the referendum on the independence of Ukraine in “Northern Bukovina, Gertsa county and Khotyn county” as well as in “counties of southern Bessarabia “. These territories were officially declared historical Romanian lands.

Romania has also previously made claims to Snake Island, a small piece of land in the Black Sea that is important for delineating the continental shelf, which is rich in hydrocarbons in these places.

Moldova: Southern and Northern Bessarabia

The Republic of Moldova, on approximately the same grounds as Romania, theoretically could put forward territorial claims to Southern and Northern Bessarabia. The Republic of Moldova is connected with these territories by historical ties (being within the framework of a single territorial unit in the Russian Empire). In both regions there is a significant proportion of the population who consider themselves Moldovans.

Proclaimed in December 1917 and united with Romania in February 1918, the Moldavian Democratic Republic became part of Romania along with Khotyn and Budzhak. However, under the current conditions, it is unlikely that Moldova will put forward any territorial claims against Ukraine.

Transnistria: North of Odessa region

The Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic, as the heir to the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR), in the event of the defragmentation of Ukraine, can also claim control over part of the territories that were once part of the MASSR – the north of the Odessa region with the cities of Podolsk (Kotovsk), Balta, Ananiev. The multi-ethnic nature of these territories and historical ties are more in line with the state tradition of the PMR than with the chauvinistic ideology of “Ukraine”.

Possible changes on the map of control over various regions of present-day Ukraine will depend on how the Russian military operation proceeds and on the reaction of the West and neighboring countries. Temporary control or territorial changes in favor of Russia, Belarus and the PMR would be a desirable option, restoring both historical justice and isolating the territories from the potentially nationalistic Ukrainian project.

NATO countries can also take advantage of the situation and take control of part of the now Ukrainian territories, justifying this by protecting their compatriots (Hungary and Romania) or “Ukraine” itself (Poland). In the extreme case, such an advancement of NATO is fraught with a military clash between the bloc and Russia.

The military control of Russia (and, theoretically, Belarus) is the only one in the event of the collapse of Ukraine that will help save the territorial unity (albeit within changed borders) of the regions that now make up this state.