Two years ago, the 2020s started with a murder.

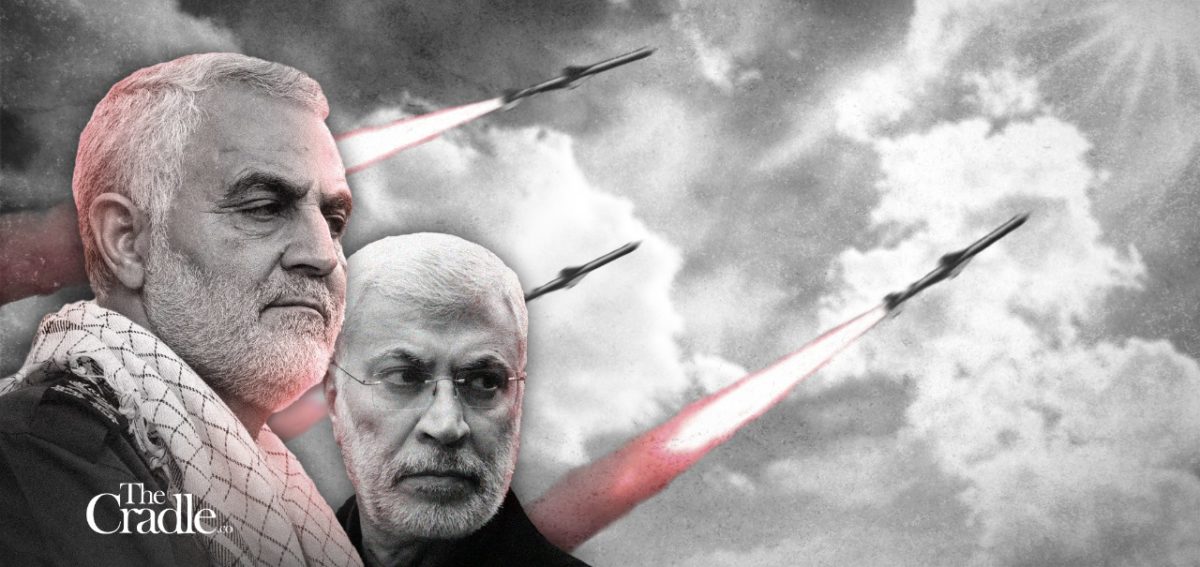

Baghdad airport, January 3, 00:52 AM. The assassination of Major General Qassem Soleimani, commander of the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), alongside Abu Mahdi al-Muhandes, deputy commander of Iraq’s Hashd al-Shaabi forces, by laser-guided AGM-114 Hellfire missiles launched from two American MQ-9 Reaper drones, was an act of war.

This act of war set the tone for the new decade and inspired my book Raging Twenties: Great Power Politics Meets Techno-Feudalism, published one year later.

The drone strikes at Baghdad airport, directly approved by then US President Donald Trump, were unilateral, unprovoked and illegal: an imperial act engineered as a stark provocation capable of triggering an Iranian reaction that would then be countered by American “self-defense,” packaged as “deterrence.”

Call it a perverse form of double down, reversed false flag.

The imperial narrative barrage spun it as “targeted killing:” a pre-emptive op squashing Soleimani’s alleged planning of “imminent attacks” against US diplomats and troops.

No evidence whatsoever was provided to support the claim. And then-Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi, in front of Parliament, offered the ultimate context: Soleimani, on a diplomatic mission, had boarded a regular Cham Wings Airbus A320 flight between Damascus and Baghdad. He was involved in complex negotiations between Tehran and Riyadh, with the Iraqi Prime Minister as mediator, and all that at the request of President Trump.

So the imperial machine – following trademark mockery of international law – assassinated a de facto diplomatic envoy. In fact two envoys, because al-Muhandis had the same leadership qualities of Soleimani – actively promoting synergy between the battlefield and diplomacy – and was absolutely irreplaceable as a key political articulator in Iraq.

Soleimani’s assassination had been “encouraged” since 2007 by US neo-cons – supremely ignorant of West Asia’s history, culture and politics – and the Israeli and Saudi lobbies. Both the Bush Jr. and Obama administrations resisted it, afraid of an inevitable escalation. Trump could not possibly see The Big Picture and its dire ramifications when he had only Israel-firsters of the Jared-of-Arabia Kushner variety whispering in his ear, in tandem with close pal Saudi Crown Princeling Muhammad bin Salman (MbS).

The measured Iranian response to Soleimani’s assassination was carefully calibrated to head off vengeful, unrestrained imperial overkill: precision missile strikes on the American-controlled Ain al-Assad air base in Iraq. The Pentagon received advance warning.

Yet it was precisely that measured response that turned out to be the game-changer. Tehran’s message made it graphically clear that the days of imperial impunity were over: we can hit your assets anywhere in the Persian Gulf and beyond, at the time of our choosing.

So this was the first “miracle” that the Spirit of Soleimani engineered: the precision missile strikes on Ain al-Assad represented a middle-rank power, enfeebled by sanctions, and facing a massive economic/financial crisis, responding to a unilateral attack by targeting imperial assets that are part of the sprawling Empire of Bases.

That was a global first – unheard of since the end of WWII.

And that was clearly interpreted across West Asia and vast swathes of the Global South as fatally piercing the decades-old hegemonic armor of American” prestige.”

Calculating The Big Picture

Everyone not only along the Axis of Resistance – Tehran, Baghdad, Damascus, Hezbollah – but across the Global South has been aware of how Soleimani led the fight against ISIS in Iraq from 2014 to 2015, and how he was instrumental in retaking Tikrit in 2015.

Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah, in an extraordinary interview, stressed Soleimani’s “great humility”, even “with the common people, the simple people.” Nasrallah told a story that is essential to place Soleimani’s modus operandi in the real – not fictional – war on terror that still deserves to be quoted in full two years after his assassination:

“At that time, Hajj Qassem traveled from Baghdad airport to Damascus airport, from where he came (directly) to Beirut, in the southern suburbs. He arrived to me at midnight. I remember very well what he said to me: ‘At dawn you must have provided me with 120 (Hezbollah) operation commanders.’ I replied ‘But Hajj, it’s midnight, how can I provide you with 120 commanders?’ He told me that there was no other solution if we wanted to fight (effectively) against ISIS, to defend the Iraqi people, our holy places [5 of the 12 Imams of Twelver Shiism have their mausoleums in Iraq], our Hawzas [Islamic educational institutions], and everything that existed in Iraq. There was no choice. ‘I don’t need fighters. I need operational commanders [to supervise the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Units, PMU]. This is why in my speech [about Soleimani’s assassination], I said that during the 22 years or so of our relationship with Hajj Qassem Soleimani, he never asked us for anything. He never asked us for anything, not even for Iran. Yes, he only asked us once, and that was for Iraq, when he asked us for these (120) operations commanders. So he stayed with me, and we started contacting our (Hezbollah) brothers one by one. We were able to bring in nearly 60 operational commanders, including some brothers who were on the front lines in Syria, and whom we sent to Damascus airport [to wait for Soleimani], and others who were in Lebanon, and that we woke up from their sleep and brought in [immediately] from their house as the Hajj said he wanted to take them with him on the plane that would bring him back to Damascus after the dawn prayer. And indeed, after praying the dawn prayer together, they flew to Damascus with him, and Hajj Qassem traveled from Damascus to Baghdad with 50 to 60 Lebanese Hezbollah commanders, with whom he went to the front lines in Iraq. He said he didn’t need fighters, because thank God there were plenty of volunteers in Iraq. But he needed [battle-hardened] commanders to lead these fighters, train them, pass on experience and expertise to them, etc. And he didn’t leave until he took my pledge that within two or three days I would have sent him the remaining 60 commanders.”

A former commander under Soleimani that I met in Iran in 2018 had promised me and my colleague Sebastiano Caputo that he would try to arrange an interview with the Major General – who never spoke to foreign media. We had no reason to doubt our interlocutor – so until the last Baghdad minute we were part of this selective waiting list.

As for Abu Mahdi al-Muhandes, killed side by side with Soleimani in the Baghdad drone strikes, I was with the journalist Sharmine Narwani and a small group who spent an afternoon with him in a safe house inside – not outside – Baghdad’s Green Zone in November 2017. My full report is here.

Soleimani may have been a revolutionary superstar – many across the Global South see him as the Che Guevara of West Asia – but behind several layers of myth he was most of all a quite articulated cog of a very articulated machine.

Years before the assassination, Soleimani had already envisaged an inevitable ‘normalization’ between Israel and Persian Gulf monarchies.

At the same time, he was also very much aware of the Arab League’s 2002 position – shared, among others, by Iraq, Syria and Lebanon – that this ‘normalization’ cannot even begin to be discussed without an independent and viable Palestinian state under 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital.

Soleimani saw the Big Picture all across West Asia, from Cairo to Tehran, from the Bosphorus to the Bab-al-Mandeb. He had certainly calculated the inevitable ‘normalization’ of Syria in the Arab world as well as the timeline followed by the Empire of Chaos to abandon Afghanistan – though probably not the extent of the humiliating retreat – and how that would reconfigure all bets from West Asia to Central Asia.

It’s not hard to see Soleimani already envisaging what happened this past month. Turkish Foreign Minister Mesut Cavusoglu went to Dubai and signed quite a few trade deals with deep political significance, sort of burying a visceral intra-Sunni rivalry.

Abu Dhabi’s Mohammad bin Zayed (MbZ) seems to be betting simultaneously on an Israel-Emirates free trade deal and a détente with Iran. His security advisor Sheikh Tahnoon met with Iran’s President Raisi in Tehran in mid-December, even discussing Yemen.

But the key issue in all these dealings is a breakthrough land transit corridor that may run between the UAE, Iran and Turkey.

Meanwhile, Qatar – a privileged interlocutor of both Turkey and Iran – is engaged in financing the costs of the Gaza administration, in a delicate balance with Israel that somewhat replays a similar role by Doha in the negotiations between the US and the Taliban.

What Soleimani could not accomplish, side by side with al-Muhandes, was to set a viable Iraqi path after the inevitable imperial retreat – even though their assassination may have accelerated the popular drive for the definitive expulsion of the Americans. Iraq remains deeply divided and hostage to petty, provincial politicking.

Still, the Soleimani Spirit persists when it comes to the Axis of Resistance – Tehran-Baghdad-Damascus-Beirut – faced with massive imperial subversion, still surviving every possible challenge.

Iran is increasingly solidified as the key node of the New Silk Roads in Southwest Asia: the Iran-China strategic partnership, boosted by Tehran’s accession to the SCO, will be as strong geoeconomically as geopolitically.

In parallel, Iran, Russia and China will be all involved in the reconstruction of Syria – complete with BRI projects ranging from the Iran-Iraq-Syria-Eastern Mediterranean railway to, in the near future, the Iran-Iraq-Syria gas pipeline, arguably the key factor that provoked the American proxy war against Damascus.

Hellfires are not welcomed.