Summary

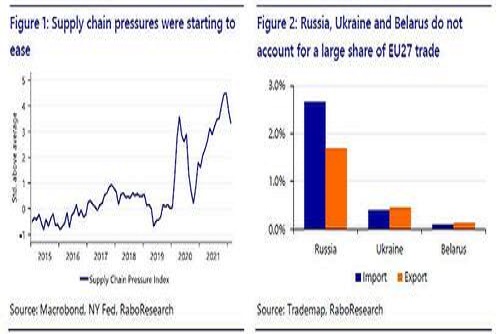

The Ukraine war has sparked another supply chain crisis, just as pandemic-related disruptions had started to ease.

- Europe depends on Russia, Ukraine and Belarus for its energy imports, but also for some chemicals, oilseeds, iron and steel, fertilizers, wood, palladium and nickel, amongst others.

- Especially the energy dependency is a vulnerability, now that Russia is demanding ruble payments for its exports. It is unlikely that Europe would be able to fully replace Russian gas in the short term, whilst most of the Russian oil and solid fossil fuels could be replaced.

- Besides energy goods, disrupted supply of pig iron and several other iron and steel products, nickel and palladium will likely have the largest impact on EU industry.

- EU supply chains could also be distorted via war-related production disruptions in third countries. The EU could face challenges in importing e.g. electronic circuits from third countries, as these require inputs such as nickel and neon gas sourced from the warzone.

- Germany and Italy are relatively vulnerable to the crisis because of their relatively large industrial sectors, strong reliance on Russian energy, and in case of Italy strong reliance on Russia and Ukraine for certain iron and steel imports and gas in its total energy mix

Will we ever catch our breath?

Just as supply chain issues caused by the pandemic were starting to ease (Figure 1), the next crisis has presented itself. The war in Ukraine is making clear that large parts of the world depend on Russia, Ukraine and Belarus for basic necessities such as food, energy and other commodities.

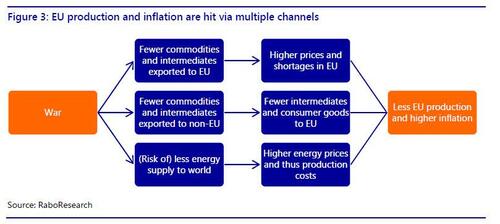

Trade with Russia, Belarus and Ukraine (referred to as the warzone in the remainder of this piece) has come close to a halt due to a wide range of sanctions, self-sanctioning (mainly by western companies), and strongly disrupted production and transport in Ukraine. Although the overall share in world trade is limited for those countries, trade disruptions can have large implications for both specific firms and industries as well as entire economies. Disruptions (both actual and feared) to imports from the warzone will hurt the EU more than less exports to the warzone. Not only because the warzone accounts for a larger share in the EU’s imports than exports (Figure 2), but especially because less imports of commodities and intermediate products can have knock-on effects on multiple production processes in the EU.

In Part I of this research note we will zoom in on the EU’s direct and indirect dependence on non-food commodities and goods imported from the warzone. We will assess which EU industry subsectors are most vulnerable for the disruptions caused by the war. In Part II we compare the vulnerability of the largest Eurozone countries.

The revival of supply chain disruptions

On top of oil and gas, Russia, Belarus and Ukraine are producers of a number of key commodities that are used in everyday items or in the production thereof– such as pig iron, palladium and neon. Next to commodities, certain industries also depend on these countries for intermediate products. A striking example is the dependence of several German car factories on certain car parts produced in Ukraine. This has already led to the closure of several German car factories.

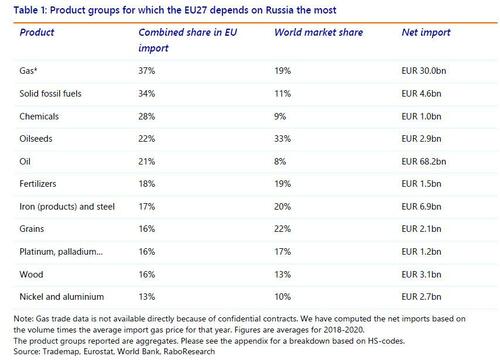

We can split up the effects on supply chains into first order and second order effects. First order effects are caused by a reduction in direct trade between the warzone and the European Union. There are two types of second order effects. The first is less trade between the warzone and third countries that results in fewer supply of products to the EU from those third countries. The second

is less EU production of intermediate goods due to higher energy prices -or even shortages- as a result of the war and, consequently, less production of downstream goods for which these intermediates serve as inputs (Figure 3).

Part I: EU dependence on goods from the warzone

We start our analysis by looking for products for which the EU27 depends heavily on Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. We then omit those products that can easily be imported from other parts of the world and those which do not play a vital economic role. For example, Germany is quite dependent on Russia for raw fur skins, but it is safe to say that Germans and the German economy will survive without fur coats.

Table 1 lists the most exposed vital economic goods based on these principles, with a minimum net import volume of EUR1bn. In the table we have aggregated certain product lines that came out on top in this analysis, to prevent getting lost in too much detail. Note that the row ‘chemicals’, for example, does not encompass all chemicals, yet only those that fulfil the above criteria. A list of the specifics for each product group can be found in the appendix. Apart from food products, the EU extensively depends on the warzone for several energy goods, chemicals, fertilizers, and metals – such as iron, nickel and palladium. And apart from, perhaps, chemicals, it seems rather difficult for the EU to find alternative suppliers for these goods and will likely at least cause price rises.

Below we will elaborate on usages and the consequences of reduced availability of the non-agri products listed in table 1 and where necessary, on specific products within those product groups. We also give some indication on the relative ease or difficulty to substitute these products.

All in all, we find that many sectors are likely to face disruptions to the supply of inputs and/or higher prices thereof. Most vulnerable seem to be production of basic metals and fabricated metal products. Other sectors that will certainly be impacted as well are construction, machinery and equipment, and transport equipment.

EU dependence on Russian energy

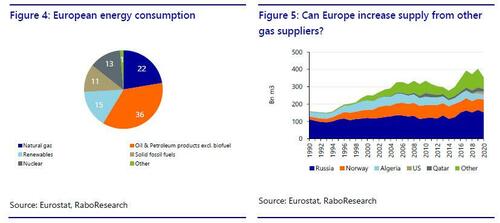

The most obvious link with Russia is on the part of energy commodities. The EU relies on Russia for 21% of its oil imports, 37% of its gas imports and roughly 45% of its solid fossil fuels imports. Energy imports are not yet subject to outright sanctions in the EU and are still flowing, but the possibility of sanctions is talk of the town. In any case, fear of reputational damage and of accidently breaching sanctions has already led to some reduction of Russian oil imports in the EU. Meanwhile, Russia is demanding ruble payments for its exports, which the EU is currently refusing to pay. For the time being, Gazprombank will help European companies to convert their euro payments to rubles, but it is still possible that gas deliverance will be weaponized. Finally, the EU has presented a plan to cut back on Russian energy dependence over the coming year(s). In other words, it is useful to dive into the EU’s dependence on Russian energy, to grasp if we could do without. Not surprisingly it appears that it won’t be easy to get rid of Russian energy altogether and it would certainly lead to a shock effect in the short run if energy trade with Russia came to a sudden standstill. It would lead to energy shortages, possibly requiring rationing of energy consumption for the industry, leading to a substantial drop in industrial production. Special thanks to our energy strategist, Ryan Fitzmaurice, for providing us with the much needed background on energy markets.

Gas

It is unlikely that Europe could replace Russian gas with alternative gas in the short run.

The most obvious way to cope with a halt of Russian gas imports, would be to replace Russian gas with non-Russian gas imports. Yet as we have already explained in a recent research note, there probably isn’t enough available gas to, suddenly, replace Russian supply. Moreover, switching to different gas suppliers also faces technical constraints. Much of Europe’s gas is supplied through pipelines in Central- and Eastern-Europe from the east to the west, which are not suitable for sending gas the other way around -at least not on a short notice.

It is also unlikely that LNG imports will fill the gap in the short run. Apart from a lack of availability -certainly in the short run-, some EU countries lack the infrastructure needed to import LNG. LNG needs to be converted to a gas state in LNG terminals before it can be transported through a network of pipelines. Germany, for example, does not have any LNG terminals and neither do landlocked countries such as Czech Republic.

Were it to come to gas shortages, switching to alternative fuels, like coal, is potentially necessary to avoid an energy shortage in the winter. But it goes without saying that increasing coal consumption is not in line with Europe’s green ambitions.

A full report on Europe’s gas dependency can be found here.

Oil

Replacing oil could be somewhat easier than replacing gas, although it would come at a higher cost. Even though some oil is transported via pipelines, it can also be transported via ship or railway, without the need to liquify it first (as is the case with gas). This means that, if Europe can get its hands on oil of a similar grade, Russian oil that is transported through pipelines in central and eastern Europe, could be replaced, albeit at a higher price. Europe would have to compete with countries that currently rely on those types of oil, potentially pushing those countries, such as India or China, to importing the (cheaper) oil from Russia.

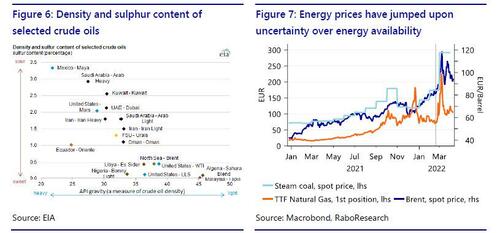

That is a big if however. Oil can differ strongly depending on its origin. Usually different oils are characterized by their sulphur content and density. Ural oil is a medium sour crude oil (figure 6). The closest replacement crudes are from Saudi Arabia, Iran and Oman. In addition, the medium sweet barrels from the North Sea, West Africa and the United states would also be suitable alternatives, with less need to desulfurize the crude (a process that is very natural gas intensive). Refineries are usually tailored to a specific kind of oil, but could switch their operations to accommodate other types of oil in a relatively short period of time, but testing and blending of the new crudes are required to ensure smooth operations.

Solid fossil fuels

Friday 8 April, the EU announced a ban on Russian solid fossil fuel imports from August. While this has induced the price for coal to increase and can hurt specific factories, in our view, the omittance of Russian coal won’t be a major problem on a macro scale.

The EU also gets about one-third of its imported solid fossil fuels -mainly coal- from Russia. At first sight, this seems to imply the EU is rather dependent on Russia for this part of its energy consumption too. But the figure overstates the importance of Russian coal imports for the EU. First, coal is not as important to most European countries as gas or oil. On average, solid fossil fuels -mostly coal- are good for 11% of total EU energy consumption (Figure 4). Second, while a couple of countries, especially in the eastern part of Europe, still rely on coal for a significant part of their energy consumption (Figure 9), most of these countries are either pretty self-reliant or mainly import their coal from countries other than Russia. Major consumer Poland for example, produces around 98% of its coal consumption domestically. Moreover, although clearly in contradiction with the green ambitions of the European Union, the EU could decide to produce more coal if push comes to shove.

Halted EU production due risen energy prices

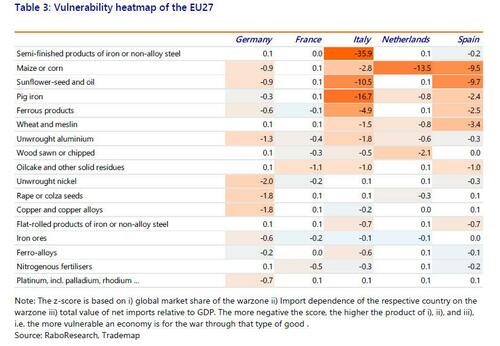

As mentioned, gas and oil imports are not yet subject to outright sanctions in the EU. Yet energy prices have jumped (Figure 7) upon uncertainty over the future of Russian energy imports in the EU, a ban on Russian oil in the US, and a voluntary drop in purchases of especially Russian oil by European buyers, amongst other things -data on the coal price is from before the announcement of the ban on Russian coal imports. Despite a drop since their war-peak, energy prices are still higher than at the start of the year and just prior to the start of the war. These higher energy prices, in turn, have led to production cuts of energy intensive products in the EU such as aluminium, zinc, steel, ceramics, concrete, bricks, glass, asphalt, paper and fertilizers – especially large gas consumers had also already taken a hit from surging prices last year. This will not only hamper the production of these specific products, but also frustrate downstream production for which these goods serve as inputs.

The disruptions will certainly hit the construction sector, a sector that was already dealing with lengthy delivery times for several inputs. Furthermore, higher input prices will likely hit margins of construction companies and project developers, raise consumer prices of construction projects, and lead to delays and cancelations of projects.

Other sectors that will see the costs of their non-energy inputs rise are for example machinery and equipment, consumer appliances, and transportation due to less steel and aluminium production. Meanwhile, less production of paper -or higher prices- will be felt across many sectors that need packaging material. And finally, lower fertilizer production in the EU adds to less supply from the warzone countries (see below), impacting especially the agricultural sector.

EU dependence on chemicals, fertilizers and wood imports

Apart from energy commodities, the EU quite extensively depends on the warzone for certain chemicals, fertilizers, certain types of wood, rubber and several types of metal.

Chemicals include carbon (black) which is used, to strengthen rubber in tires for example, and ammonia which is mostly used to produce fertilizers. Combining the former with the EU’s dependence on Russia for the ‘end product’ rubber (12% import market share), there could be an impact on the car sector. That said, based on world market shares it should not be too difficult to shift to other suppliers if importers are ready to pay a somewhat higher price. Limited availability of fertilizers due to lower imports from the warzone and less production in the EU poses a challenge for agriculture and hence ultimately the food sector. Meanwhile, Russia is the world’s largest exporter of lumber and is an important supplier of different types of wood for the EU’s construction sector and fuel wood. Although we do not expect any shortages here, due to the wide availability of wood from other parts of Europe, we do expect higher prices.

EU dependence on metal imports

Table 1 also shows a large dependence on the warzone for different metals with in some cases limited diversification possibilities. Should the prices of products mentioned below rise, delivery times are likely to lengthen as it usually takes time to find alternative suppliers. In some cases actual shortages could arise -although it is difficult to get a grip on the timing thereof due to missing details on the size of stocks.

Most vulnerable in this respect are sectors making use of iron and steel, nickel, palladium and aluminium: basic metals and fabricated metal products, machinery and equipment, transportation, computer and electronic products, and construction.

Iron and steel

To illustrate, more than 50% of EU imports of pig iron -used to make steel-, ferrous ore products, semi-finished iron and non-alloy steel products, and waste from iron and steel production comes from the warzone. Especially for pig iron and waste there are few alternatives as the warzone has a world export market share of respectively 63% and 52%. But also for the ferrous and semi-finished products diversification will be difficult, given the world market share of 30% and 40%. Fewer steel imports from the warzone adds to pressure in the market from less production in the EU itself due to the risen energy prices. Iron and steel have a broad range of destinations. They not only end up in the basic and fabricated metal industry, but also construction, production of machinery, equipment (that obviously includes ‘military’) and automotive.

Nickel and aluminium

Another important metal with availability at risk is nickel. Nickel is essential for rechargeable batteries, medical devices, automotive, and electrical and electronic equipment. It is also used in construction and to make stainless steel. The EU gets 90% of its nickel mattes’ imports from the warzone and 20% of its unwrought nickel. Russia is in the top three of global exporters of nickel -playing musical chairs with the US and Canada- and has a global export market share of 15%. Moreover, it’s a very tight market, especially due to nickel being required in rechargeable batteries, with ever growing demand due to the world’s push for electrification. Hence it is likely to be challenging -at best- to replace nickel imports from Russia and will for sure induce higher costs. With regards to aluminium, Russia is the steady number 2 exporter in the world, with a market share of 10%. Some 12% of EU imports of unwrought aluminium is sourced from Russia. Fewer aluminium imports from Russia adds to pressure in the market from less production in the EU itself due to the risen energy prices. Aluminium has a broad range of applications and is used for, for example, wires and cables in electrical equipment, in construction, transportation, machinery and equipment and electronic products, e.g. consumer appliances.

Palladium and platinum

The final metal we will highlight is the rare metal palladium. EU import dependence on Russia is 27%, with Russia having a world export market share of 23%. Palladium is a by-product of nickel and platinum mining, amongst others, and hence it is tough to ramp up production. In other words, the EU is both very dependent on Russia and it won’t be easy to get a grip on alternative supplies -at least not at favourable costs. Importantly, palladium is used as a catalytic converter in cars: in both gas engine cars to reduce the emission of polluting gasses and as a catalyst in hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. It is also used in multilayer ceramic capacitors and hard disks, which in turn can be found in laptops and phones for example. Other uses of palladium are in sensors, chips, surgical instruments and dentistry. For most applications there are alternatives such as platinum, although opinions on the quality of substitutes differ. Currently, the EU gets 9% of its platinum imports from Russia, and the latter’s world export market share is 7%. Yet, if palladium is being replaced by e.g. platinum, clearly the price of the latter would likely explode as well -unless the world’s largest platinum producer South Africa more or less doubles its platinum production.

To sum it all up

So, in short, the EU -and also the world- depends heavily on Russia, Ukraine and Belarus for several key inputs to its industrial sector. Among those commodities are gas, oil, iron and steel products, nickel, palladium, several chemicals and aluminium. Combined, the products in table 1 only account for some 1% of EU GDP. Yet their value alone does not give the full picture of their importance to lengthy industrial value chains -and food security as far as the agri-related commodities are concerned.

Gas and oil are still flowing, but a sudden stop in Russian gas imports would clearly have significant ramifications for the entire industrial sector. Risen energy prices have already curtailed EU production of energy intensive products. Meanwhile, halted or limited inflows of the non-energy commodities certainly has an impact on the price of these products and lengthens delivery times, which will be felt by multiple industrial subsectors.

Topping the list of most exposed sectors are basic metals and fabricated metal products. Thereafter we find construction, chemicals, coke and refined petroleum products, wood and paper, machinery and equipment, and transport equipment with more or less the same impact score. Whereas risen energy prices have a higher impact on some, commodity shortages and higher prices of non-energy goods are more problematic for others.

Second order effects via non-EU countries

Apart from vulnerabilities due to direct trade links between the EU and the warzone, the EU will likely also be impacted via trade with third countries. In this respect, vulnerable product groups are motorcycles, electronic circuits, batteries and electronics and electrical machines.

To get a feeling for second order effects that run via non-EU countries, we adopt a two-step approach. First, we look at the product categories for which the European Union is not self-sufficient. Unfortunately, it is hard to find any consumption data on this level of detail, so we look at the average ratio of imports to exports over the last couple of years. Second, we filter the data to exclude product groups with a trading volume smaller than EUR 1bn. Third, we have excluded the goods that already popped up in the analysis of direct trade links between the EU27 and Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.

The second step is to look at whether these products -are likely to- consist of inputs coming from the warzone and/or include inputs which have experienced large price rises due to the war. Due to the globally intertwined supply chains and data gaps in this respect we have to resort to proxies in some cases. We start by listing products for which the warzone countries have a significant world market share. The larger their combined market share, the larger the chance that producers depend on the warzone countries. And even if producers don’t rely on the warzone themselves, they are likely to be confronted with price increases if manufacturers in other countries start looking for alternatives for their inputs from the warzone. For products where the warzone countries have a combined world market share above 10%, we check whether these products are commonly used in the production process of the goods in table 2.

We also have to take into account whether the dependency relies on goods and commodities from Russia or Ukraine. China, for example, has not yet joined the west in imposing sanctions on Russia, and thus for now Russian goods will continue to flow to China. For Ukraine it is different, however, given that production has (partially) come to a standstill.

Some of the product groups listed in table 2 are vulnerable due to the current sanctions or the production fallout in the warzone. This mainly holds for motorcycles, electronic circuits, batteries and electronics and electrical machines.

Motorcycles

Motorcycles production is dependent on long, optimized supply chains and is therefore vulnerable to any disruption whatsoever. Moreover, most new motorcycles are packed with chips (see below) and other electronics (which were already in short supply before the war started!) and are built using steel, aluminium, plastics and rubber. Russia is a global player when it comes to steel and aluminium production, but China as well. Japan depends on imports when it comes to aluminium and articles thereof, yet has a major steel industry itself.

Electronic circuits and diodes

(Electronic) circuits and diodes are mostly made of purified silicon. Silicon is the second most abundant element on earth after oxygen, so silicon is not the constraint for circuits. The production process also requires an inert gas, for which neon, krypton and xenon gases are often used- in fact, these gases are said to be essential for the semiconductor manufacturing industry. With some 70% of world supply, Ukraine is the world’s largest producer of the required purified form of neon gas. It also supplies respectively 40% and 30% of global demand for krypton gas and xenon gas. Two major Ukrainian producers of purified neon gas in Odessa and Mariupol have already halted production. Meanwhile, Russia is a major player when it comes to the production of the crude version of neon gas, given that the latter is a by-product of the steel industry. China, with its large steel industry, is another major player in both the crude and refined production, although it would need to increase its activities to be able to fulfil domestic demand and it is uncertain at what pace it could expand production -China currently also imports neon gas from Ukraine. At the start of the invasion, stocks at major semiconductor manufacturers worldwide were estimated to be enough for some 6 months of chip production.

Batteries

Batteries are currently in high demand since they pay a vital role in the energy transition. Batteries are mostly made from steel and nickel. We have already touched upon the former above. Especially the latter could prove to be an issue. Nickel is currently in a really tight spot, given that Russia supplies roughly 18% of the worldwide nickel exports and high demand due to the world’s push for electric vehicles. Whilst buying nickel from Russia could be an issue for Japan, for now it is unlikely to be an issue for China, however. Other materials used in batteries, such as zinc, manganese, and graphite are mainly produced in China, whilst again others such as cobalt are produced in Congo, but are directly controlled by China.

Electronics and electrical machines

Electronics and electrical machines will likely be impacted indirectly through a crunch of the already tight market for electronic circuits. Additionally, some of the appliances make use of rechargeable batteries, which in turn are affected by shortages and/or higher prices in nickel markets. Other inputs for these type of products with tighter world supply are aluminium, palladium and steel. But, again, for the time being China -which is the EU’s major supplier of electronics and electrical machines-, need not to be harshly impacted as it is still refraining from sanctioning Russia and is one of the largest global aluminium and steel producers itself.

To conclude, the EU might be confronted with lengthened delivery times or higher prices of some final goods imports from third countries, such as motorcycles and electrical machines. Yet also intermediate imports from third countries such as chips and batteries could become more difficult to get by. This, in turn, could hamper EU production of transport equipment, machinery, and electronic products and electrical equipment.

Conclusion part I

Even though the imports from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus only make up a small share of the total imports and exports of the European Union, it is clear that the war in Ukraine is wreaking havoc in supply chains. The most obvious impact is from higher energy prices, and maybe, if sanctions escalate, an outright energy shortage. Sanctions on gas imports are the most likely catalyst for such a crisis, whilst oil and coal imports are easier to replace.

As we will show in the second part of this publication, Germany and Italy are worst suited to deal with such a crisis because of their relatively large industrial sector and heavy reliance on Russian energy, gas in particular. France and Spain on the other hand, are better equipped to deal with such a crisis, although it needs to be said that no country will be left unscathed.

But it’s not just energy that is posing a serious threat to supply chains. As we have shown in the report, there are plenty of other materials and products, such as nickel, palladium, iron, wood and neon (and agri-commodities of course!), that threaten supply chain disruptions in some industries, especially in the short run as it takes time to find supply elsewhere. Some supply chains will be directly impacted through their dependence on Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, whilst others may be impacted indirectly, through second order effects.

Part II: Which member state is the most vulnerable?

In the second part of this publication, we compare the exposure of the five largest EU economies to distortions caused by the war. We find that the German economy is most exposed, followed by the Italian economy.

Direct trade linkages between member states and the warzone

Just looking at the macro picture for the EU27 might understate some of the problems in specific member states. Since, even if there is a surplus in timber in Poland for example, that doesn’t necessarily mean that that surplus can be exported to Spain easily if the infrastructure isn’t there. Additionally, it would be naïve to assume it can be done at a similar price and ease. As such it is useful to zoom in on member states to see for what goods they rely on the warzone the most.

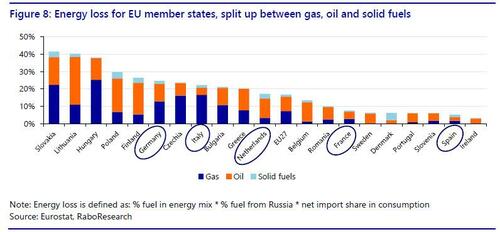

To compare member states we adopt a similar methodology as we did to create table 1 for the EU 27, but use z-scores to compare the relative vulnerability for the five biggest economies in the EU. Table 3 presents the relative vulnerabilities related to non-energy products for which at least one of the five large member states strongly depends on the warzone, via direct trade linkages. Given the importance of energy security we will dedicate a separate section to the reliance on Russian energy. The products in table 3 are ranked based on the combined z-scores of the member states for that product group.

Semi-finished products of iron or non-alloy steel top the list, due to Italy’s strong links with the warzone in this respect. Maize, sunflower-seed and oil, and pig iron are other products that stand out.

Out of the five largest member states, Italy seems most exposed to the war through direct trade linkages with the warzone. It relies heavily on the warzone for pig iron and semi-finished products of iron or non-alloy steel. Some 84% of its imports of the former come from the warzone and 77% of the latter. Italy also gets 82% of its ferrous products imports from the warzone, yet the (net) trade value of this category is substantially smaller. Finally, its dependence on warzone sunflower seeds and oil stands out.

Spain is relatively dependent on the warzone for agri-commodities, like maize and sunflower seeds. Respectively, some 32% and 66% of Spain’s imports of these products comes from the warzone at relatively large net-volumes. It also substantially relies on the warzone for pig iron and ferrous products.

The Netherlands is especially dependent on the warzone for ‘maize or corn’. Roughly half of Dutch maize/corn imports are from the warzone. This could severely impact the price and availability of animal fodder, as is evident from the fact that Dutch farmers have already begun to hoard animal fodder.

For Germany, the biggest vulnerabilities (next to energy) are unwrought nickel and copper, metals that are vital to German industry. Roughly 45% of Germany’s nickel imports and 24% of its copper imports come from the warzone.

France seems least vulnerable to the war-induced supply crunch. Yet it is exposed to a halt in oilcake imports; oilcake can be used as fodder and fertilizer.

Energy dependence of member states on Russia

In order to gauge the vulnerability of European countries to a potential collapse in Russian energy exports, we have gathered data on the consumption, trade and domestic production of oil, gas and solid fossil fuels. Based on this data, we can compute the share of energy consumption for which alternative sources would need to be found if imports of Russian energy come to a halt.

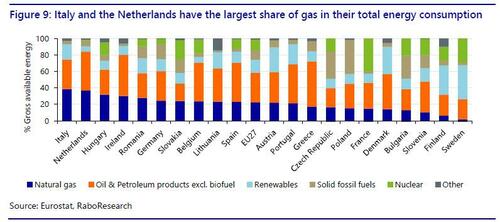

Looking at figure 8 it is evident that especially countries in Eastern and Central Europe are set to lose in case of an energy boycott. These countries have been able to acquire Russian fossil fuels for attractive prices in the past decades, partially because of the large network of pipelines that run through Eastern and Central Europe. This has given them no incentive to diversify their energy mix or decrease the reliance on Russia. Yet also, Finland, Germany, Italy and Greece get more than 20% of their energy consumption out of Russia, while in the Netherlands it is only slightly less.

Meanwhile, Scandinavian countries rely on Norway for gas and oil imports, whilst they simultaneously have relatively large shares of renewable energy; the Iberian Peninsula relies on Algeria for gas and France but also Belgium are relatively large producers and users of nuclear heat (Figure 9).

As we have argued before in the section on Europe’s energy dependence, replacing all of these fossil fuels will not be easy. Replacing Russian oil and solid fossil fuels may be possible, albeit at a higher price, but replacing Russian gas will not be as easy. Simply supplying more LNG, if this is even possible, will not do the trick in the short run. Whilst some countries, such as Spain, the Netherlands and Italy, have the terminals to convert LNG to regular gas, landlocked countries such as Czechia, but also Germany do not. Currently, the infrastructure is lacking to transport freshly converted gas to those countries and hence those countries are even more vulnerable to a stop in Russian gas imports than others -which explains Germany’s most outspoken resistance to banning such imports. For the full report on Europe’s gas dependency, we refer to this publication.

Importantly, this analysis is primarily focussed on the availability of energy, but even if we don’t get to the point where energy availability is an acute issue, high energy prices impact all countries, whether they are dependent on Russia or not. Especially member states with a large share of gas in their energy consumption such as Italy and the Netherlands have seen their energy bills rise substantially -already last year. Relatively large coal consumers also seem to have a cost disadvantage compared to those consuming more oil. If current prices would be sustained until the end of the year, gas, coal and oil bills would on average be about, 9, 4 and 1.7 times larger this year than in 2019, respectively. Compared to last year, bills would increase less, but still be 1.6 times larger in case of gas and oil and 2.5 times in case of coal.

How about the sectoral composition?

Next to the vulnerability related to certain key commodities and (intermediate) products, the economic impact of the war in Ukraine is also determined by the economic composition of a country. Basically every sector in an economy is impacted by the higher energy prices, but some are more than others3. Additionally, some sectors rely heavily on commodities that are currently in tight supply and are unable to transfer some of the higher commodity prices to consumer prices.

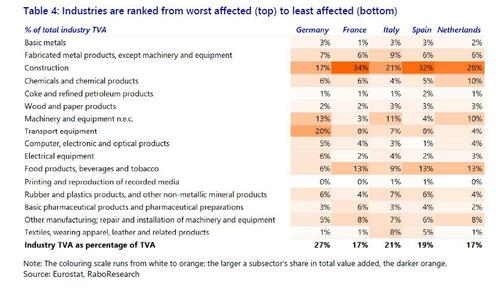

Most service sectors are left relatively unscathed, whilst the industrial sector is feeling the pinch. Based on the energy intensity, exposure to commodities for which prices have risen, and exposure to commodities that are in short supply, we have ranked industrial subsectors from most to least likely to be impacted (Table 4).

It needs to be said that while it is clear that basic metals and fabricated metal products rank at the top and textiles at the bottom, there is a broader ‘middle’ group with more or less the same impact score. In table 4 this group ranges from construction to electrical equipment. Whereas risen energy prices have a higher impact on some, commodity shortages and higher prices of non-energy goods are more problematic for others. If we combine the ranking with the relative size of the industrial subsector per country, we can compare the relative vulnerability for the industries of the five biggest Eurozone member states.

Based on their composition, industries in Germany and the Netherlands seem most vulnerable, but the differences are small. The fact that Germany has a relatively large transport and machinery sector for example, is compensated for by the fact that the German food industry is relatively small.

Conclusion part II

The economic fallout of the Ukraine war is felt by the entire EU, with higher volatility in commodity markets, lengthened delivery times and higher prices for a range of commodities. Highly intertwined supply chains make it difficult to isolate the exact economic impact of the war on different member states, but we explored a method to grasp the relative vulnerabilities of the five largest EU member states.

According to our analysis the German economy is most at risk to face headwinds caused by the war due to the composition and size of its industrial sector, and its dependence on Russian energy. Next in line is Italy. Italy’s industrial composition seems slightly more favorable, but it is relatively large as well. Furthermore, Italian industry extensively depends on Ukraine and Russia for certain industrial steel inputs and energy. Finally, Italy is a large gas consumer, and hence relatively more impacted by the increase in energy prices so far.

By Maartjie Wijffelaars and Erik-Jan van Harn of Rabobank

Read More