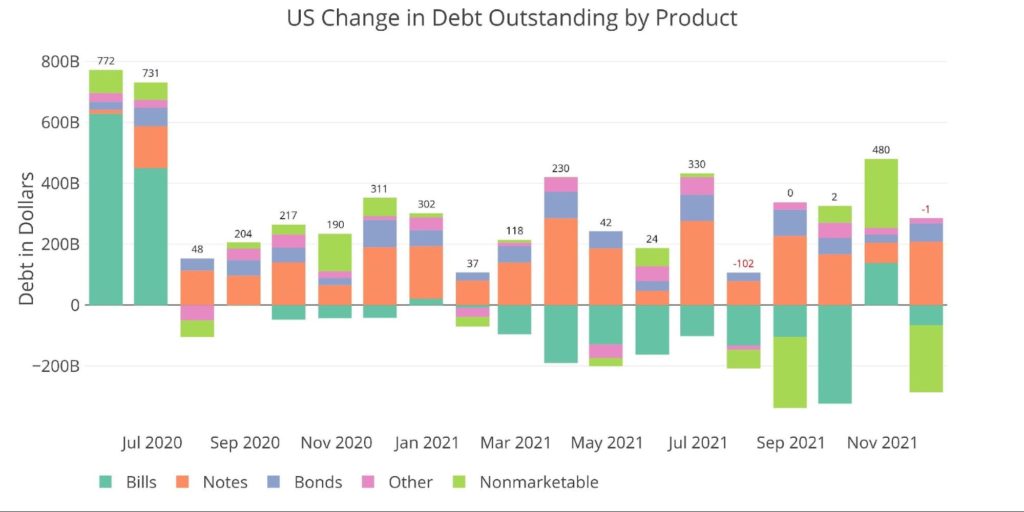

Similar to August and September, the total debt has not increased due to the current debt ceiling in place. Similar to August, the Treasury has raided public retirement accounts to continue funding government spending (light green bar below). Even so, Covid has forever shifted the landscape of US Debt.

The chart below also highlights a trend that has been in place all year: the Treasury is rapidly converting short-term Bills to medium-term Notes (shown by a reduction in the turquoise bar and increase in the orange bar). The Treasury is scrambling to extend maturities as quickly as possible because it reduces the short-term risk of higher rates. It will extend the window the Treasury has before rising rates prove catastrophic. Unfortunately, even with this strategy, the window is shrinking rapidly.

Figure: 1 Month Over Month change in Debt

The Impact of Higher Rates

The Fed has told the market, they will use their tools to fight the highest inflation in 31 years. Unfortunately, that will prove extremely difficult given the current debt levels of the US Government. Because the total debt outstanding has not changed this month, this analysis will focus on a table usually reserved for the end of the debt analysis.

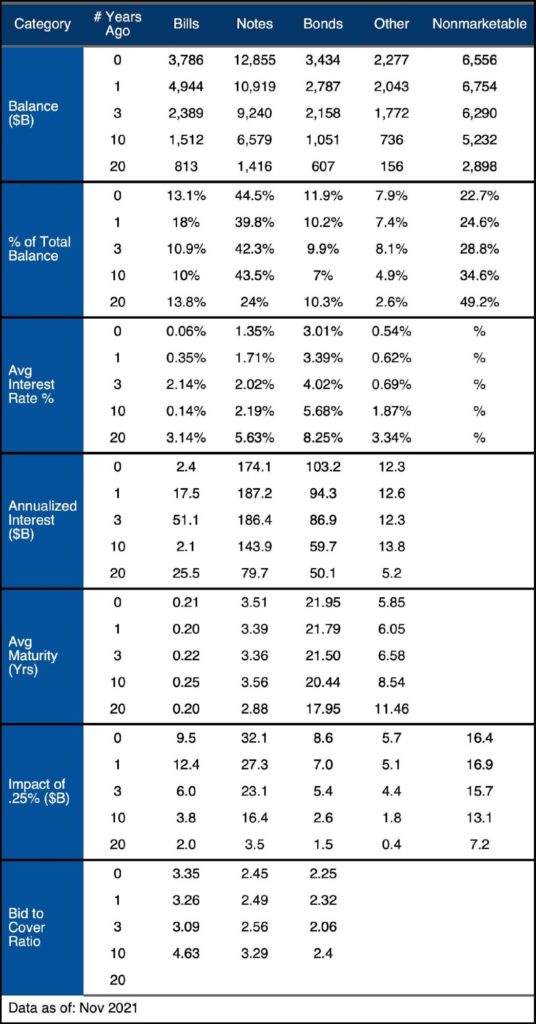

Figure: 2 Debt Details over 20 years

This table may be challenging to read, but it’s critical in understanding just how much the Fed is boxed in. Each section shows a different part of the debt (total balance, relative distribution, avg rate, etc.) and then shows how the numbers have changed over 20 years.

The second to last section may be the most important: “Impact of .25% ($B)”. This section shows how much interest payments would increase for each quarter-point rise in rates. This section must also be contextualized with the section above that shows Avg Maturity (yrs). This represents the time it would take for a rate increase to work through the debt.

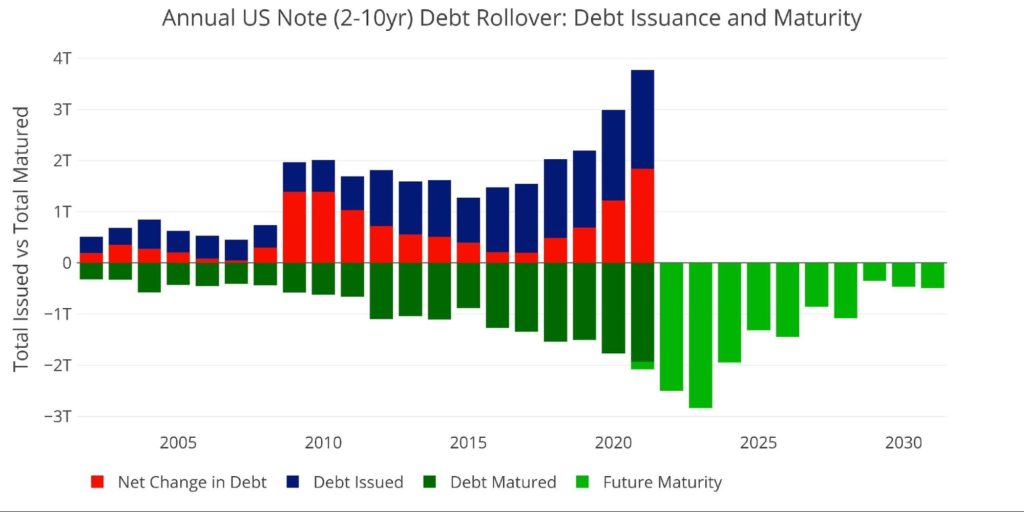

For example, the chart below shows the maturity schedule for all Notes outstanding (bright green bars).

Figure: 3 Treasury Note Rollover

As shown above, even though there is $12.8T in Notes outstanding, “only” $2.5T comes due in 2022, $2.8T in 2023, and $1.9T in 2024. This represents half of the total Notes outstanding. A rate increase of .25% on $12.8T is $32B a year. Simple math says rates rising by 1% would increase interest by $128B. However, not all of that will happen right away. Furthermore, the composition of maturing debt must be considered.

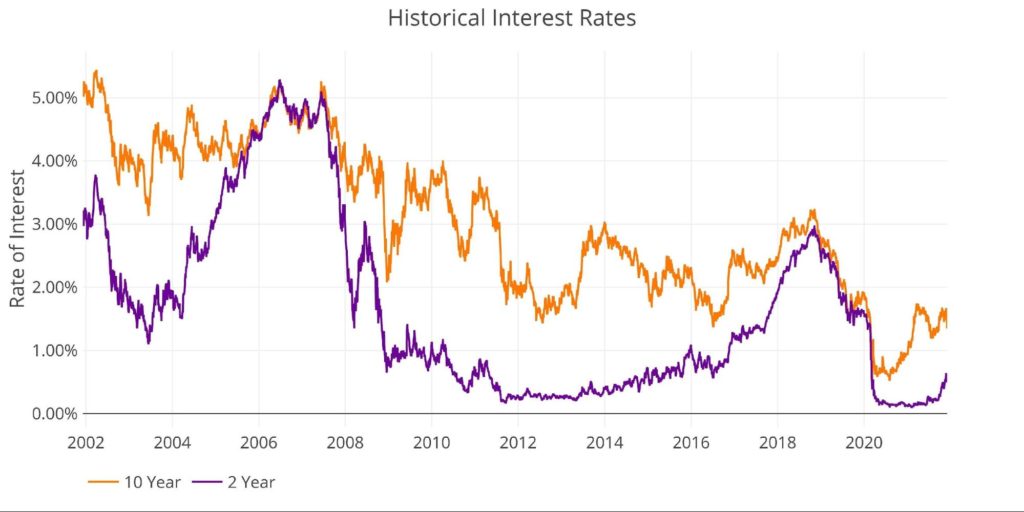

The average interest rate is 1.35%, but that could still mean higher interest rate debt is maturing in the next three years. Specifically, 10-year notes issued between 2012-2014 when rates ranged between 1.6%-3%. 2-year rates are also much lower compared to 2 years ago (see chart below). This relief in 2-year debt is about to fade as Covid enters year 3.

Figure: 4 Interest Rates

One other consideration is the Fed owns $6T of all US Debt outstanding, concentrated in the 1-5 year maturities. All coupon payments made by the Treasury are returned to the Treasury. Anything held by the Fed is an interest-free loan.

With this context, the math gets more complex.

Bills

The Fed owns $1.1T in Treasury Bills or $29% of total outstanding. This means the Treasury would owe $6.5B per year for each quarter-point rise instead of $9.5B. Unlike Notes, the maturity for all Bills happens within a 12-month period, the vast majority of which occurs within 6 months. Thus a 1% rise translates to $26B within a few months.

Notes

The Fed owns $3.1T of $12.8T outstanding (25%), two-thirds of which is in the 1-5 year bucket. Assuming that all debt rollover increases by the same amount, a 1% increase will end up costing the Treasury just under $100B. Over half of that will be realized by year 3 with the remainder being a factor over the following 7 years. After the first year of higher rates, interest payments will climb by $20B followed by an additional $23B per year after 24 months (adjusted for interest-free Fed holdings).

Bonds

Bonds are a different story. Most of the bonds maturing will be refinanced at much lower rates. Interest rates would need to rise to above 6% for bonds to start increasing the burden for the Treasury. For now, they are benefiting from rolling over debt that has been locked in for 20+ years.

For simplicity, these can net against “Other”

Visualizing the problem

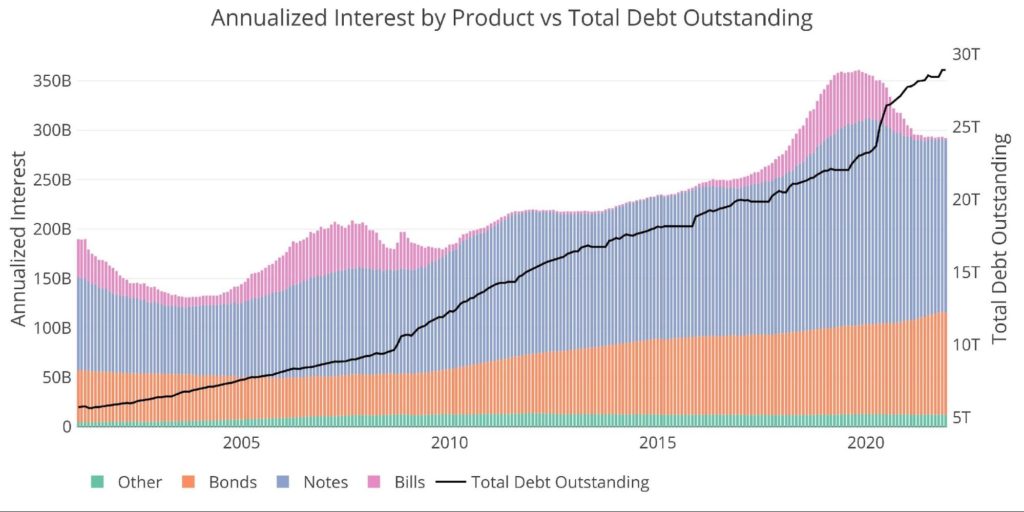

The chart below says it all. The last Fed hike took an annualized interest above $350B from $250B very quickly. When Covid hit and rates dropped, the interest on Bills collapsed and Notes interest drifted downwards. Bonds and Other barely budged in the short time rates had increased.

Note: the order and colors have reversed to better visualize the impact of Bills and Notes.

Figure: 5 Annualized Interest by Product

Rates only reached 2.5% during the last rate hike cycle. Since rates dropped, the black bar shows total debt increasing from $23T to $29T. The problem has grown by 25% in two years! With the Treasury desperate to raise the debt ceiling and keep the debt binge going, $30T will be in the rearview mirror shortly.

If the last slow and methodical hike cycle created a $100B increase in 2.5 years, what happens if the Fed has to get aggressive to bring inflation down? The time frame shrinks and rates go higher. Catastrophic!

Conclusion

A 1% rate increase would result in higher debt servicing costs by about $45B in 12 months, increasing to $85B by year 3 (assuming the Fed doesn’t shrink its balance sheet). This means a 5% increase in rates, which is still below the current inflation rate, would cause debt payments to increase by $225B within year one and $425B by year 3! This would more than double the cost of the debt.

Furthermore, compared to just three years ago, the implied debt cost of rising rates is up 50%. Compared to 20 years ago it is up 4x in Bills and 8x in Notes. Anyone who justifies the current irresponsible behavior with the excuse “it hasn’t been a problem so far” does not understand how dramatically the landscape has changed.

So, does the Fed have the tools to fight higher inflation? Sure. But there is no way to use those tools without destroying the Federal budget deficit, much less the rest of the economy. Don’t forget that higher rates would create a massive recession due to all the debt elsewhere in the economy. Plunging tax revenue and increased fiscal spending would exacerbate the issue dramatically.

The Fed can talk all they want, but all they can do is pray inflation comes back down. They sure can’t fight it!

Data Source: https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/mspd.htm