New Delhi’s pitch to host COP33 in 2028 is instrumental in giving the world’s most populous country leverage in the international fight to save the planet

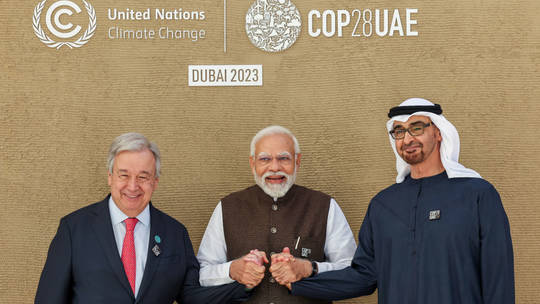

Addressing the first day of the Conference of Parties (COP) in Dubai on 1 December, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that his country could host the conference (COP33) in 2028.

The surprise announcement echoed one he made eight years ago, when India teamed up with France to introduce the International Solar Alliance (ISA) on the first day of the COP meeting in Paris. Expectations then were that India would be intransigent at the negotiations, forcing a stalemate at a time when the world was desperately seeking a blueprint to fend off the growing threat of climate change.

In fact, India’s proactive stance paved the way for a historic climate deal wherein member countries committed to cut emissions by 2030 and submit to a review at this year’s meeting in Dubai. It was a defining moment for Indian climate diplomacy, which until then had been perceived as a compulsive naysayer which continued to insist that developed nations had to bear the responsibility for the legacy of carbon emissions.

Accordingly, India backed a deal which compelled individual member nations to adhere to differing sets of commitments. The updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), approved in 2022, aims to reduce emissions intensity by 45% by 2030.

It is not that India has abandoned its stance. In fact, PM Modi alluded to it in his pitch when he said at the COP meeting in Dubai that “India has set an example for the world to have a perfect balance between ecology and economy. Despite India having 17 percent of the world’s population, our share in global carbon emissions is less than four percent.” India reinvented its approach to climate policy and went from being part of the problem to part of the solution.

It was able to do so by aligning its domestic objectives, in this case green growth, with its international commitments, thereby eliminating friction in the national political discourse.

At the same time, by creating the ISA, India emerged as the co-owner of an international institution in the climate-adjacent space. While the recalibration of its climate ‘persona’ provided India with flexibility, the creation of institutions like the ISA has allowed it the freedom to negotiate on different platforms and on specific subjects. The ISA has focused on garnering investment and technology for solar installations in the global South.

As a result, India has gone from being a reluctant player to emerging as a key global forse in battling climate change. The pitch to host COP33 is therefore a continuation of this strategy and indicates the maturing of India in global climate politics.

COP Tactics

First off, by offering to host the COP summit in 2028, India is reiterating that it is not going to walk back the commitments made at Paris and the promise to go net zero by 2070.

India is also reinforcing its newly acquired diplomatic agility by establishing co-leadership positions in multilateral and minilateral frameworks. The idea is to leverage these platforms along with bilateral engagements to secure finance and technology to enable domestic decarbonisation.

It is estimated that developing countries, excluding China, will need about $2 trillion every year to enable climate mitigation. While this estimate is staggering, even the financing made available so far has come in the form of loans. To make matters work, several countries are facing a debt crisis in the aftermath of the turmoil first brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic.

At the same time, most of the technology, including for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, is located in developed countries.

Furthermore, 2030 is a key year in the battle against climate change. It will see whether the commitments made in Paris have been honoured. Hence, by offering to host COP, India is in a strategic position to shape the contours of the next global climate deal.

Today India’s nominal GDP is only $3.5 trillion. Its goal is to evolve into a developed, $15 trillion economy by 2047. In order to do so, it will need continued access to energy. National priorities will alter depending on how the intervening negotiations which take place before COP33. So far, India has not shared anything with the public.

While renewable energy capacity has been witnessing a rapid increase in the country over the past decade, India will still need to rely on fossil fuel to feed its growing demand for energy. The country will therefore be very keen on steering away from a new climate agreement which denies it this option.

However, in order for New Delhi’s plan to be operationalised, it will have to be accorded the right to host COP33. It is not a done deal. For example, Australia had offered to host COP31 in 2026, but will now have to compete with Türkiye, which threw its hat in the ring last week.

If India does end up hosting COP in 2028, it will be the second time – the country hosted COP8 in 2002.

Regardless, it is clear that increasingly India, driven by the sheer size of its population and potential economic growth, is being counted as an important player in shaping the battle against climate change.

By Anil Padmanabhan, freelance journalist and former managing editor of Mint newspaper