Yesterday saw major developments from both the ECB and the Fed. In both cases, it was sadly amateur hour.

The ECB, less than a week after saying it didn’t need a “concrete plan” for Euro fragmentation risk as it raised rates, was forced to hold an emergency meeting to provide one due to the surge in Italian yields: it said, “We will get back to you.” Their plan is a promise to come up with a plan. El-Erian was saying yesterday that the Fed risks looking like an emerging market central bank, channelling my recent DM = EM meme: and the ECB came across as a bad EM central bank. (By contrast, Brazil just hiked rate 50bps with no drama. They might want to offer lessons.)

My colleagues cover this Eurosis in more detail in ‘Pain threshold hit already?’, noting the ECB statement leaves much uncertainty over how powerful its intervention will actually be. We expect more clarity in July, and its vagueness may contain spreads for now, as the market will not want to try the ECB’s hand ahead of the formalization of any instrument. However, once an anti-fragmentation tool is known and markets will know its limitations, that arguably gives traders a new target to aim for – and they will go for it. Especially if it just says, ‘Build Back Better’.

There are lots of ways the ECB can act via acronyms. However, clearly there can be no end to ECB QE as they raise rates – as posited here was logical; or they can’t raise rates at all; and there can’t be any real QT. Moreover, the ECB raising rates and doing QE is now both monetization and mutualization. So, logically, we have a central bank that de facto “prints” money… and very inefficiently for the real economy. Regular readers might recall my thought-piece from mid-2020 asking how we were going to justify our political-economy when it doesn’t work anymore. The ECB is now a case in point: is “because Euro” enough for everyone ?

So to the Fed, where we got a first-since 1994 75bps hike following the leaks planted in the press during a supposed blackout period. Yet markets rallied hard because:

-

the Fed had leaked it, rather than shocking them, so undoing the point of a bigger move;

-

because Powell then refused to cement a 75bps move in July, as if the inflation dynamic he suddenly watches will have changed in a few weeks; and

-

because he also stressed there will be a soft landing – as the drop in retail sales and the Atlanta Fed survey suggests a reasonable chance the US is already in a technical recession.

The market also liked that the Fed’s projected long run rates projection was clustered around 2.50%. Yet there is no sign that broad commodity inflation is under control to match, leading President Biden to now lash out at over-stretched-and-about-to-be-windfall-taxed US refiners for causing inflation. And Russia just cut gas flows to Germany by 40% and to Italy by 15%. That long-run rate is really a loooong way out until the supply side is sorted out.

Our Fed-whisperer Philip Marey argues in ‘75 not the new 50, but maybe again next time’ that the Keystone Cops from the Eccles Building are again behind the curve. He now sees the Fed Funds rates having to move closer to 4% by year end, with 75bps in July, and then three 50bps hikes in a row. Then we get a US recession (or perhaps another one) in H2 2023. As such, one would posit the huge bull steepening in the US curve and the post-FOMC equity rally are both likely to be reversed ahead.

Tomorrow is then the BOJ and their “Hey, ECB, hold my beer!” yield curve control policy – as yesterday saw the 10-year JGB yield break as high as 0.29% before being brought back down to 0.246% again via yet more intervention. When that peg eventually breaks, markets are going to get hit hard. Japan is currently a source of ultra-cheap financing in a world of rising rates, and with a currency that is only going one way – down. If both reverse at once,… ouch!

Only Korea would be really happy: it goes head-to-head with Japan in many export markets, and is openly saying it is facing an economic crisis as the BOJ goes all-in. They will arguably need a Fed swap line soon. So will many others as US rates rise. Yet the Fed will only be handing them out to geopolitical friends, i.e., what about Türkiye and its crumbling TRY, as it places its S-400 anti-aircraft missiles facing towards Greece, flies a UAV over a Greek island, and blocks Swedish and Finnish NATO membership?

That’s ironically central banking coming full circle to its origins as a vehicle for national security and Grand Strategy, a point I have repeated before. Nobody created central banks to be inefficient money printing machines, or for rich people. They had a far more important purpose. They likely will have to do so again – but do you think this collective bunch of amateurs are the ones to lead that particular charge?

First-time readers will see, and regular readers will know, that I do not show much of the usual market deference for central banks or central bankers. But why should we?

Epistemologically, how can any bureaucrat have any true idea of what is happening in any one economy and national financial market, with all its moving parts, let alone when it is cojoined to the global?

Methodologically, how can they have any idea what effects their actions will or won’t engender when based on a theoretical neoliberal economic framework that would be laughed out of the room if presented as any form of hard ‘science’?

Heuristically, after their initial creation to finance wars (such as the Bank of England vs. Napoleon), central banks’ modern-day track record is one of almost continual policy failure – it’s just that we refuse to take the big picture view to frame it properly, instead focusing on the here-and-now pockets of coincidental historic ‘success’. A quick time-line recap of ‘amateur decades’ follows.

Pre-WW1 central banks are seen as having worked well under a gold standard. Actually it was British imperialism that tied things together. The global system ‘worked’, in a far simpler economy, by ripping off swathes of countries at gunpoint: and even then inflation swung massively positive and negative all the time. The gold peg was what mattered, not inflation. Then America got too big, and Germany got too big for its boots and tried to copy British imperialism. That was the end of the pre-WW1 period.

Post-WW1 central banks never all got back on a milquetoast gold standard due to huge war debts, or destroyed societies where they tried if they didn’t let credit boom anyway. All they rustled up was fascism, the Wall Street Crash, the Great Depression, and then Nazism and WW2.

Post-WW2 central banks under Bretton Woods and Cold War saw international capital flows regulated and credit rationed or allocated in a hypothecated manner domestically. As such, even their Keynesian models couldn’t screw things up too badly, and we got 25 years of low inflation and solid GDP growth. Yet the Triffin Paradox kicked in, and the US was forced off gold, and Bretton Woods collapsed. Then we saw deregulation of capital flows domestically and externally.

Central banks decided that following monetary aggregates was then the key to keeping inflation in check, because “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Except this policy didn’t work in the slightest, because once you deregulate markets, especially allowing US dollars to flow to the Eurodollar market, all your M0, M1, M2, M3 data are useless. Central banks had to abandon the policy framework.

Only with the emergence of true globalisation did inflation plunge and stay low – due to the breaking of unions, privatisation, and offshoring, especially to cheap-as-chips China. Again, this was nothing to do with central banks – who nonetheless took all the credit.

Such deregulation of course caused rolling financial instability, but the central bank response was always to cut rates into any crisis to blow more air back into the global bubble. Likewise, as society became more unequal and real wages lagged behind productivity growth, the response was to push up asset prices, not wages. Greenspan was the “maestro”. Then we got the GFC in 2008-09, which central banks’ didn’t see it coming at all despite being ‘experts’ in it.

Then it was the post-2009 ‘new normal’ decade, where central banks tried to get inflation back up to 2% by making rich people even richer with acronyms, and the ECB did “whatever it takes”, leading to yesterday’s door opening to structural, inefficient, mutualised monetisation of debt.

Then we rediscovered fiscal and monetary policy during Covid in 2020…and inflation came roaring back.

In short, central banks can look smart for a long time, but entirely due to exogenous developments. They can blow things up by being crazily ahead of the curve, or very much behind it. But most of the time they are just making it up as they go along.

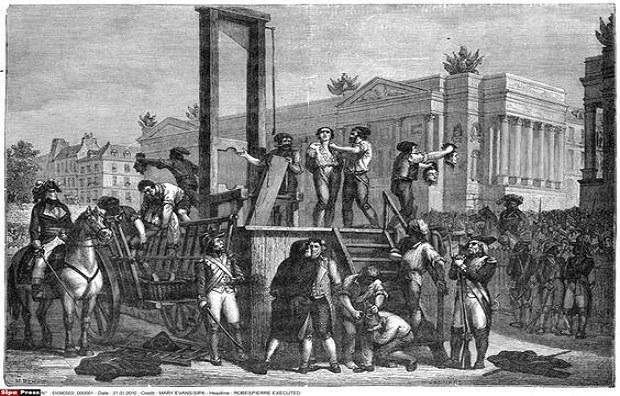

Arguably the worst sin they can commit is to *show* they don’t know what they are doing and are making it up as they go along. Amateur hours are dangerous because, as with royalty, the risk is the mystique and magic wears off, and people start asking awkward questions. Or sharpening guillotines.

Not that gold is any better – or crypto. The sad fact is that nothing works for long in a complex, dynamic system such as a globalized financialised economy. Logically, if we want true stability then we really shouldn’t have one. That’s not a forecast by the way, even if it is partly the zeitgeist.

For now, we are going to get much higher US rates, and then a recession – and then lots of questions about how things might work better than they currently do.

China has some ideas on that front. The PBOC is already unique among central banks with its lack of independence, as is China’s ‘common prosperity’ idea of avoiding Marxist “fictitious” capital, when that’s pretty much all the Western system has to offer. Building on that base, China will now require foreign funds based there to set up internal communist party units that will carry out “party activities”. That will make for some interesting morning calls – but at least the assessment of how foreign central banks’ policies work –or rather don’t– will be more accurate.

Michael Every of Rabobank