For months, the West has been projecting a geopolitics of “isolating” Russia, both economically via sanctions and diplomatically via creating anti-Russia counter alliances around the world. But how is this geopolitics of “isolation” working? Five months into the Russian military operation in Ukraine, the fallout of this war – in particular the fallout of Western sanctions – has led to the highest ever inflation rate across Europe and the US. According to their own reports, the German economy is “moving into recession.” Inflation in the UK has reached a 40-year high of 9.4 per cent, deepening the cost-of-living crisis. But the emphasis remains on “isolating” and “defeating” Russia. As Biden’s latest visit to the Middle East projected in so many words, the grand delusion has not yet given way to a more rational assessment of how the crisis in Europe has not led to an identical crisis, despite sanctions, in Russia. Its economy remains sound, as Moscow continues to make crucial gains in the international arena.

Let’s talk about Russian gas exports post-Western sanctions. The “Power of Siberia 2” gas pipeline project is in the middle of execution, a gas project that will divert Europe-bound gas to China. This pipeline will, thus, directly offset the European threat of completely cutting off their gas imports from Russia. Hence, the question: Is there even a credible European threat? While Russia supplied, until sanctions were imposed, 35 billion cubic meters of gas per year to Germany, the completion of “Power of Siberia 2” will allow it to supply, via Mongolia, 38 billion cubic meters of gas to China. This has led Russia to assert its dominance. Last week, Russia’s Gazprom energy producer told its European customers that it cannot guarantee future gas supply due to unusual circumstances. This absence of a Russian guarantee hardly reflects the stance of a country under pressure from sanctions and/or facing “isolation.”

While the building of a second major pipeline to China will add to Russia’s strength, the fact that China is buying gas from Russia despite all the pressure from the US speaks volumes about Russia’s diplomatic strength drawing from a vision for a new, multipolar global order. The convergence reaffirms China’s no-limits friendship with Russia, a relationship that has been forged by a consistent US geopolitics of ‘encircling’ China and Russia.

Beyond China, Russia’s stand in the Middle East stays strong. Vladimir Putin’s visit to Tehran and talks with Iranian and Turkish leaders counter-acts, yet again, the western objective of inflicting “isolation” on Russia. This is much more than mere meetings. They have a substance from which a real meaning can be inferred that shows the West’s drastic failure.

With regards to Iran, there are reports of growing military cooperation between Moscow and Tehran. Iran’s growing ties with Russia could also be a gateway to a new Middle Eastern geopolitical landscape.

Consider this: countries like Saudi Arabia have so far resisted US pressure to get rid of the OPEC+ deal with Russia. And, they have no intention of violating this deal either. America’s “exit” from the Middle East has allowed these states to exercise a high degree of strategic autonomy in developing and managing external ties. The energy centric ties with Russia are crucial, which could provide the basis for Russian mediation in normalising Gulf Arab states’ ties with Iran. This might already be happening insofar as President Biden’s anti-Iran rhetoric during his latest tour to Israel and Saudia left no impact.

In fact, no sooner did Biden leave Saudia than Saudi Foreign Minister told CNN that Saudi ties with Iran are improving. Prince Faisal bin Farhan said this despite the recent Iranian claim that they had already acquired the technical capability to build a nuclear device. Russia’s de facto ‘oil alliance’ with Saudia, therefore, is showing its impact elsewhere as well. A greater Russian role in the region can help get rid of unnecessary regional troubles. This increasing Russian integration with the Middle East hardly indicates Moscow’s “isolation.”

Elsewhere, Russia’s ties with Turkey, a NATO member, remain strong. In fact, Ankara, unlike Brussels, is playing a role that has the potential to reduce the negative impact of the war caused by western sanctions. On July 13, Turkish defence minister announced that Russia and Ukraine have agreed in talks held in Istanbul to establish a secure corridor for exporting Ukrainian grain via the Black Sea. These talks did not feature any US or EU/NATO representatives, although it was the first face-to-face meeting between the two warring sides since the beginning of the war in late February.

Turkey’s role outside of the ambit of NATO is tied to Ankara’s own quest for a larger global role. This role has also been facilitated by persistent US failure to show sensitivity to Turkish interests. While Athens recently confirmed that it was going to buy 20 F-35s from the US, Biden’s only assurance to Erdogan was to ‘consider’ Ankara’s purchase of F-16s.

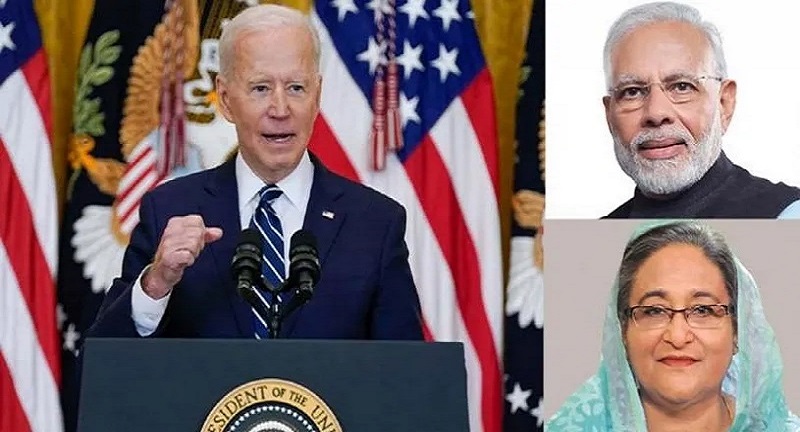

Therefore, if the core purpose of Biden’s visit, as Jake Sullivan noted, was to build an anti-Russia front, two key players in the Middle East are playing along Russia in ways that directly undercut US policies.

Therefore, while the West (US and EU) may have cut off its ties with Russia, they need to understand that the world has already largely shifted to a multipolar order that has drastically reduced any international actor’s ability to unilaterally impose its will. Western obsession with “isolation” shows a mindset trapped in the Cold War mentality refusing to recognise its limitations and/or the largely changed world.

Salman Rafi Sheikh, research-analyst of International Relations and Pakistan’s foreign and domestic affairs, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.