In talks with Sergei Lavrov this week, Secretary Blinken certainly has diplomatic options. The question is, will he pursue the right ones?

First, the declaration of a moratorium on Ukrainian membership of NATO for a period of 20 years, allowing time for negotiations on a new security architecture for Europe as a whole, including Russia.

But continue they will. For one thing that the United States and NATO have made absolutely clear is that there will be no war between the West and Russia. Western diplomats will remain in Moscow and Russian diplomats in Washington and European capitals. The West’s statements that we will not defend Ukraine have been reinforced by the evacuation of diplomats and military personnel from that country. It also goes without saying that none of the hawkish Westerners calling for “support” to Ukraine have the slightest intention of risking their own lives to defend that country.

So in the event of Russian occupation of more Ukrainian territory, Russia will use this to put pressure on the West to make concessions, and the West will use economic sanctions to put pressure on Russia to make concessions. On both sides, however, the goal will be to reach an eventual political agreement. For all the bloviating talk on both sides, and NATO’s symbolic deployment of forces to Russia’s borders, neither Russia nor the West have the slightest intention of fighting each other.

If by the time of the Blinken-Lavrov meeting, Russia has not in fact invaded Ukraine, and any military clashes remain confined to the Donbas, then all these Western warnings about an “imminent” Russian invasion will start to look a bit silly, and it will be clear that Moscow is still open to a diplomatic solution to this crisis (albeit of course quite ready to use military threats to try to gain Western concessions, or flexibility).

On the other hand, Moscow has made it clear that it is not prepared to accept a negotiating process that drags on endlessly without result—as for example has been the case with the Donbas peace process over the past seven years, and with the fake NATO-Russia “dialogue.” A Russian invasion remains a real possibility unless a compromise with Russia can be found. Every sensible and decent person agrees that a full-scale war in Ukraine, with the likelihood of an ensuing global economic crisis would be a catastrophe for Ukrainians and extremely bad for Europe, the United States, and the world.

Sensible U.S. strategists also agree that for Russia to become completely dependent on China would be very bad for U.S. interests. Averting a Russian invasion without sacrificing basic Western interests and principles should therefore be the primary goal of U.S. policy and of Blinken’s approach to Lavrov at their next meeting.

The goal for Blinken and the U.S. negotiating team in the meeting with Lavrov must be to avert war by bringing about a withdrawal of the Russian forces deployed close to Ukraine’s borders since the start of last December, backed by a public statement by the Russian government that its threat of a “military-technical” response to Western actions has been withdrawn. The proposals from the U.S. side should be the following:

First, the declaration of a moratorium on Ukrainian membership of NATO for a period of 20 years, allowing time for negotiations on a new security architecture for Europe as a whole, including Russia. The West would sacrifice nothing by this, since not even the most ardent proponents of Ukrainian NATO membership believe that this is possible within the next two decades; and NATO’s manifest unwillingness and inability to defend Ukraine means that in fact it will never be possible.

Second, a U.S. commitment to ratify the (Adapted) Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty in return for a Russian commitment to return to the terms of that treaty.

The reason for the refusal of NATO countries to ratify the treaty was the continued presence of Russian troops in the separatist regions of Georgia and Moldova. This presence does not however threaten or otherwise affect NATO and should therefore be treated separately as part of negotiations on a resolution of these disputes. The West would also have to continue to turn a blind eye to Russian peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh—something it has been happy (very inconsistently) to do, since those peacekeepers protect Armenians who have a considerable say in the domestic politics of France and America.

Under a return to the CFE, the United States would withdraw the forces it has stationed in eastern Europe since the 1990s, and Russia would withdraw the forces it has stationed on the borders of Ukraine, together with new forces stationed in the Kaliningrad region since the 1990s.

Third, building on an offer already made by the Biden administration to discuss the stationing of missiles in Europe, the United States should offer to return to the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty, with enhanced controls and safeguards for both sides, if Russia will do the same. It should be noted that the breakdown of this agreement was initiated by the United States in its withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, a withdrawal opposed at the time by leading European members of NATO.

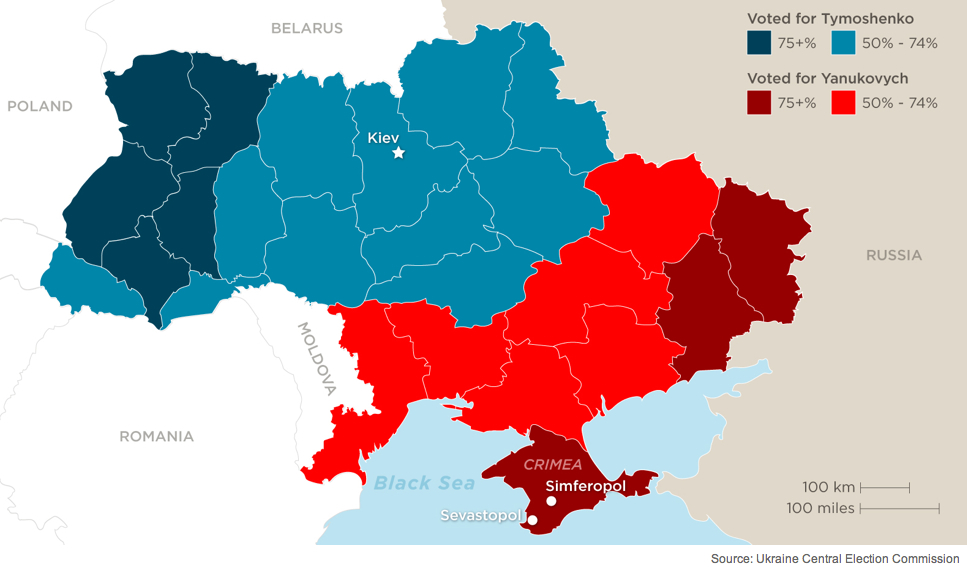

Fourth, the United States should signal its genuine and sincere commitment to a solution of the Donbas conflict on the basis of the Minsk II agreement of 2015. This will require a clear statement that the first step in the implementation of that agreement must be a constitutional amendment passed by the Ukrainian parliament guaranteeing full and permanent autonomy for the Donbas within Ukraine; though of course, accompanied by a proviso that this amendment will only come into effect when United Nations monitors have certified that the Donbas militias have demobilized, Russian “volunteers” have withdrawn, and a UN peacekeeping force has taken ultimate responsibility for security in the region.

So far, the United States, while paying lip service to the agreement, has acquiesced to Ukrainian conditions that make it in practice impossible; and has turned a blind eye to statements by Ukrainian ministers that make it clear that Kiev has no intention whatsoever of abiding by its terms. Autonomy for the Donbas within Ukraine is the only possible peaceful solution to this conflict. Without it, the Donbas will remain a festering source of future war.

Finally, the United States should state its commitment to the UN as a basis for a wider agreement on European security. Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. unilateralism has gravely devalued the only institution that retains a measure of true global legitimacy, and on which leading Western states, Russia and China are equally represented. Blinken should propose to Lavrov a new UN process aimed at the solution of all the present unsolved territorial disputes in Europe (including those in the Balkans) on the basis of common standards of local democracy.

To put it frankly, as a result of this process Russia would eventually have to recognize the independence of Kosovo, and the West would have to recognize the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and the Russian annexation of Crimea. The Donbas and Transdniestria however could be resolved on the basis of autonomy within Ukraine and Moldova. Neither side would sacrifice anything real by this. Serbia cannot reconquer Kosovo, and Ukraine and Georgia cannot reconquer their lost territories from Russia.

No doubt some will say that an offer along these lines is “politically impossible” for the Biden administration. Then again, U.S. agreement with China was “impossible” for America in the 1960s, until it turned out to be possible after all due to the courageous initiative of President Nixon and Henry Kissinger. It is the task of responsible statesmen to make what is necessary possible, and great international crises should be the spur to such acts of statesmanship. And if not now, when?