First reported by Michael Shellenberger, new details about the “Burisma leak” tabletop exercise of summer 2020 reveal a notable betrayal of principle by two famed papers.

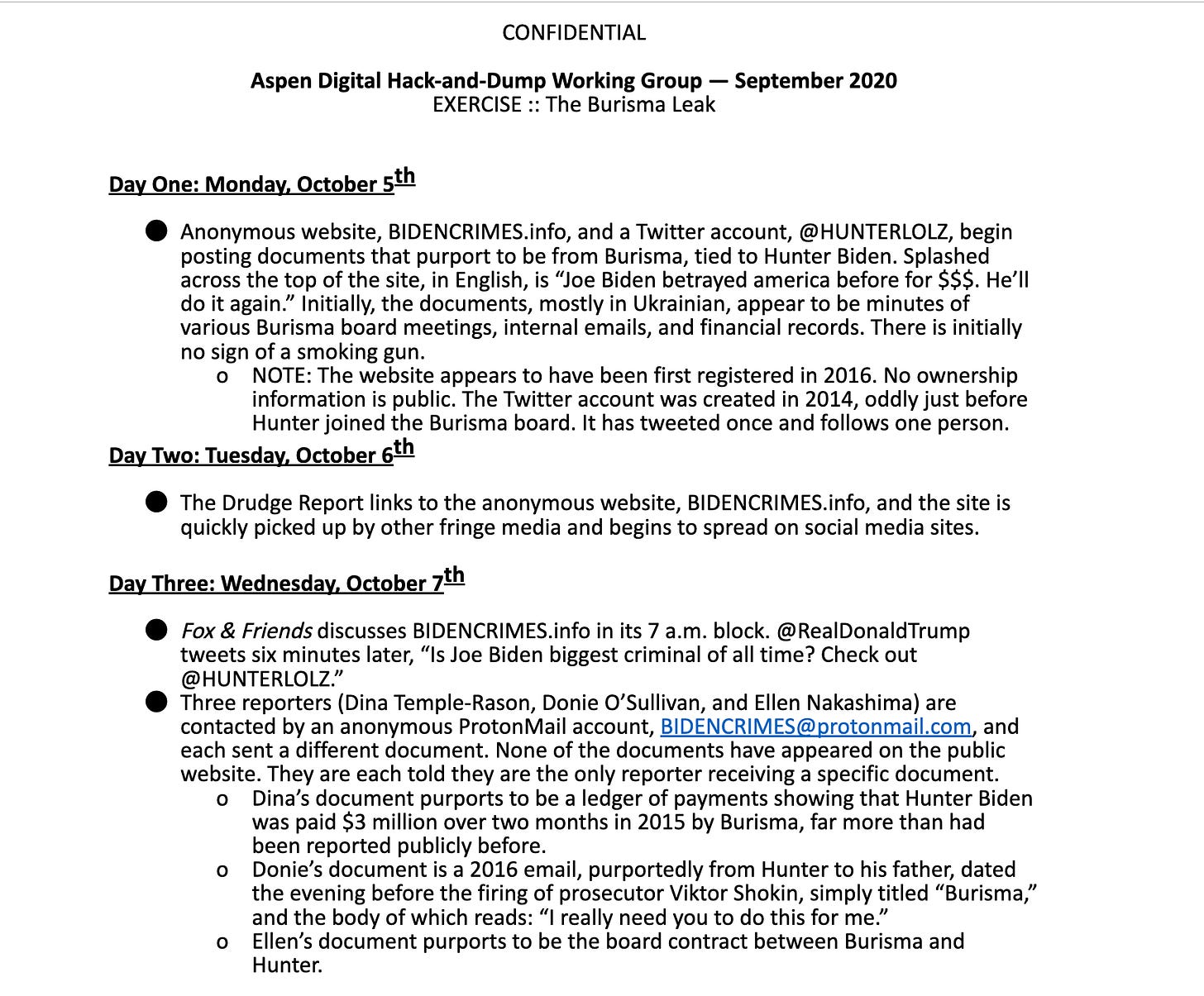

Last December, Michael Shellenberger reported in a #TwitterFiles thread that the Aspen Institute hosted a “Hack-and-Dump Working Group” exercise in the summer of 2020 titled, “Burisma Leak,” which predicted with uncanny accuracy an upcoming derogatory story in the New York Post about Hunter Biden’s lost laptop.

The documents Shellenberger published showed how at least five media figures, including David Sanger and David McCraw of the New York Times, Ellen Nakashima of the Washington Post, then-Daily Beast and future Rolling Stone editor Noah Schactman, and Rick Baker of CNN worked alongside Twitter and Facebook’s chief moderation officers, Yoel Roth and Nathaniel Gleicher, to plan a response to a hypothetical damaging exposé about Joe Biden’s son.

The “Burisma Leak” exercise predicted many elements of the real response to the New York Post’s coming Hunter Biden story, including complaints from influential Democratic congressman Adam Schiff about its “source and veracity,” and public statements from “former senior intelligence officials” falsely raising the specter of a “Russian operation.”

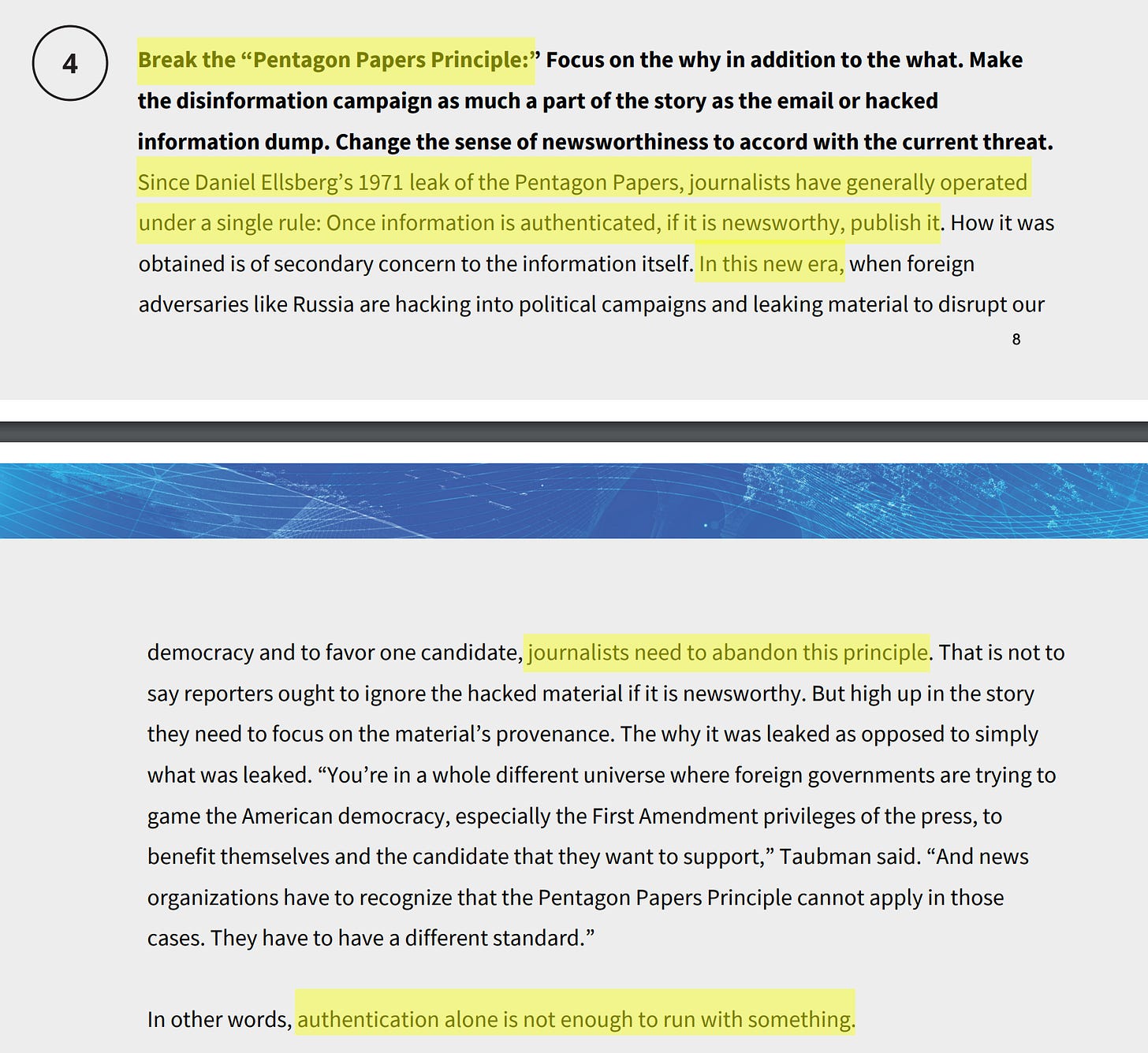

Newly uncovered documents show the war-gamed, choreographed response to the New York Post piece in October, 2020 — which included temporary suppression by those tech platforms Twitter and Facebook — may have been part of a broader plan to re-think basic journalistic standards in general, beyond just the one incident. This included junking what experts involved with the tabletop exercise referred to as the “Pentagon Papers Principle,” under which journalists since Daniel Ellsberg’s 1971 leak had “operated under a single rule: Once information is authenticated, if it is newsworthy, publish it.”

The “break” from the age-old standard was endorsed by multiple current and former figures from the Washington Post and New York Times, the two papers most associated with the publication of the Pentagon Papers. Neither of the press offices of the two papers would comment, nor did individual figures named in the #TwitterFiles leaks.

The genesis of this idea appeared to come from a paper co-authored by two Aspen tabletop attendees, both from Stanford: longtime journalist Janine Zacharia and former Obama and Trump Cybersecurity Policy Director Andrew James Grotto. Their “How to Report Responsibly on Hacks and Disinformation: 10 Guidelines and a Template for Every Newsroom” included the idea of ditching the “Pentagon Papers Principle,” insisting, “authentication alone is not enough to run with something.”

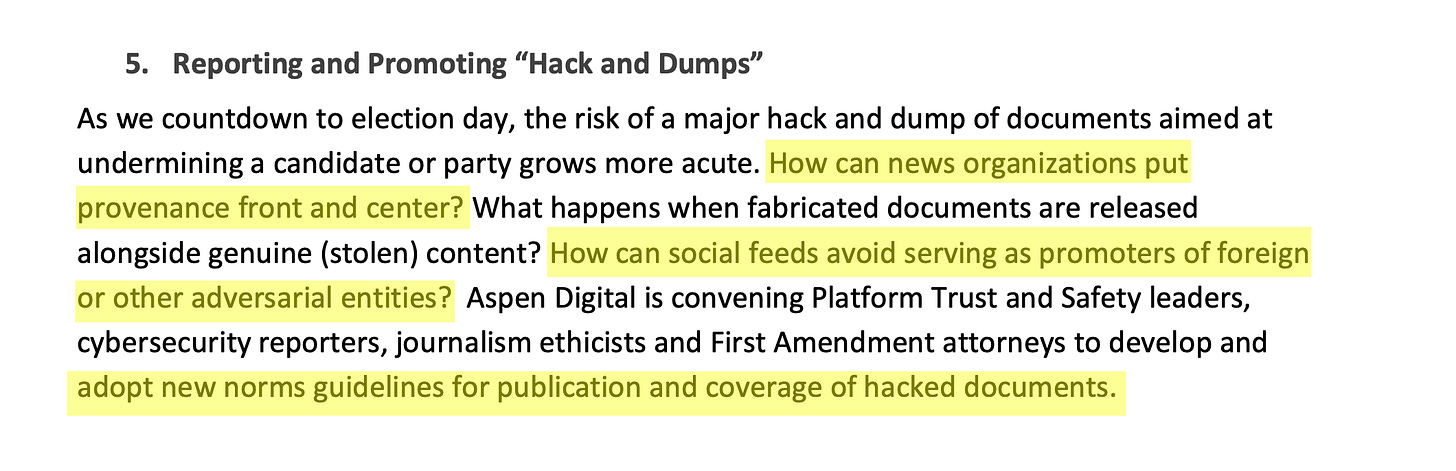

The concept seemed to provide the intellectual foundation for shelving the Post story, which otherwise presented a real conundrum for would-be censors, being neither fake news nor a Russian plant. The elaborate carve-out for dealing with such material is laid out in another newly discovered document, called “Partnership for a Healthy Digital Public Sphere: Opportunities & Challenges in Content Moderation.”

This summary was sent by Aspen Digital’s Executive Director and former NPR CEO Vivian Schiller to two other Aspen figures on September 15, 2020. Echoing the Stanford paper, it summarized the lessons Aspen Digital learned from examining the hack-and-dump problem, explaining the need to put “provenance front and center”:

The concept theoretically represented a major shift, asking reporters to move from focusing on the what of news to why? and who from?

“That seems to be the whole predicate of why they ignored the laptop story, even though they knew it was real,” says Miranda Devine, author of the New York Post exposé.

Again, none of the media or academic figures involved with this story commented for the record, but one tabletop attendee who asked not to be named did defend the decision, saying: “It was just arguing for discretion over whatever sells,” adding, “The race to the bottom is what got us 2016.”

The road to the “break” seemed to begin on August 31, 2019, when Zacharia, a former Washington Post reporter and Stanford lecturer, wrote an article for the San Francisco Chronicle titled, “Time is Running Out to Fight Disinformation in 2020 Election.” In it, she made two key arguments. One was that people could “radically slow the spread of disinformation” by removing the “retweet or share buttons” on Internet platforms. Another idea was “eliminating false content,” which she conceded “will have free speech advocates crying foul.”

Within the next month, Zacharia participated in a Stanford “Global Digital Policy Incubator” that was hosted by the Federal Election Commission. The open session was hosted by FEC chief Ellen Weintraub, who was a key figure in 2017 in getting Facebook, Google, and Twitter to accept tighter regulation on political content like ads. Her keynote speaker that day was also her partner in that 2017 endeavor, omnipresent anti-disinformation hawk and Virginia Senator Mark Warner. The session is publicly available. Zacharia reportedly spoke in a closed session, where according to her own account she “road-tested” the ideas that would appear in her “10 Guidelines and a Template for Every Newsroom” paper.

On December 13th, 2019, Stanford held a journalism workshop at which Zacharia’s ideas were discussed. Also offered as reading material was a Washington Post piece co-authored by Stanford figures Renee DiResta, former Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul, and Alex Stamos, about how “we’re still not ready” for a Russian attack in the 2020 election, as well as links to a series of materials offered by anti-disinformation shops like FirstDraft and The Open Society Foundation. These papers warned of a coming flood of fake news that would snake its way into legit media through back doors — say through a “local” outlet too understaffed to fact-check a wrong story.

Only in select spots did participants hint at the real reform being sought, what an early draft of the Zacharia-Grotto paper called “models of journalistic self-restraint.” Citations included a New York Times reporter in 1958 deciding not to publish after seeing a U2 plane on a German base, and a spate of organizations deciding not to publish the name of the alleged “whistleblower” in the Ukrainegate fiasco. Although these passages continued to be framed in terms of “disinformation,” the major reform being contemplated here involved true reports. How could competitors be urged to exercise “restraint” at the right times?

“What is needed,” Zacharia argued, was a “speed bump,” one that would be recognized not just across organizations but across industry. She and Grotto would eventually quote Phillip Corbett of the New York Times in saying, “The single most important thing is to fight the impulse to publish immediately.”

By March 27, 2020, Zacharia and Grotto published their paper. The final “top 10 recommendations” started by suggesting that “in the event of an extremely newsworthy hack, have the top editor send an organization-wide email instructing all staff not to live-tweet the content,” and to indicate instead to readers that “you are aware of the development and your reporters are working to determine the provenance of the material.”

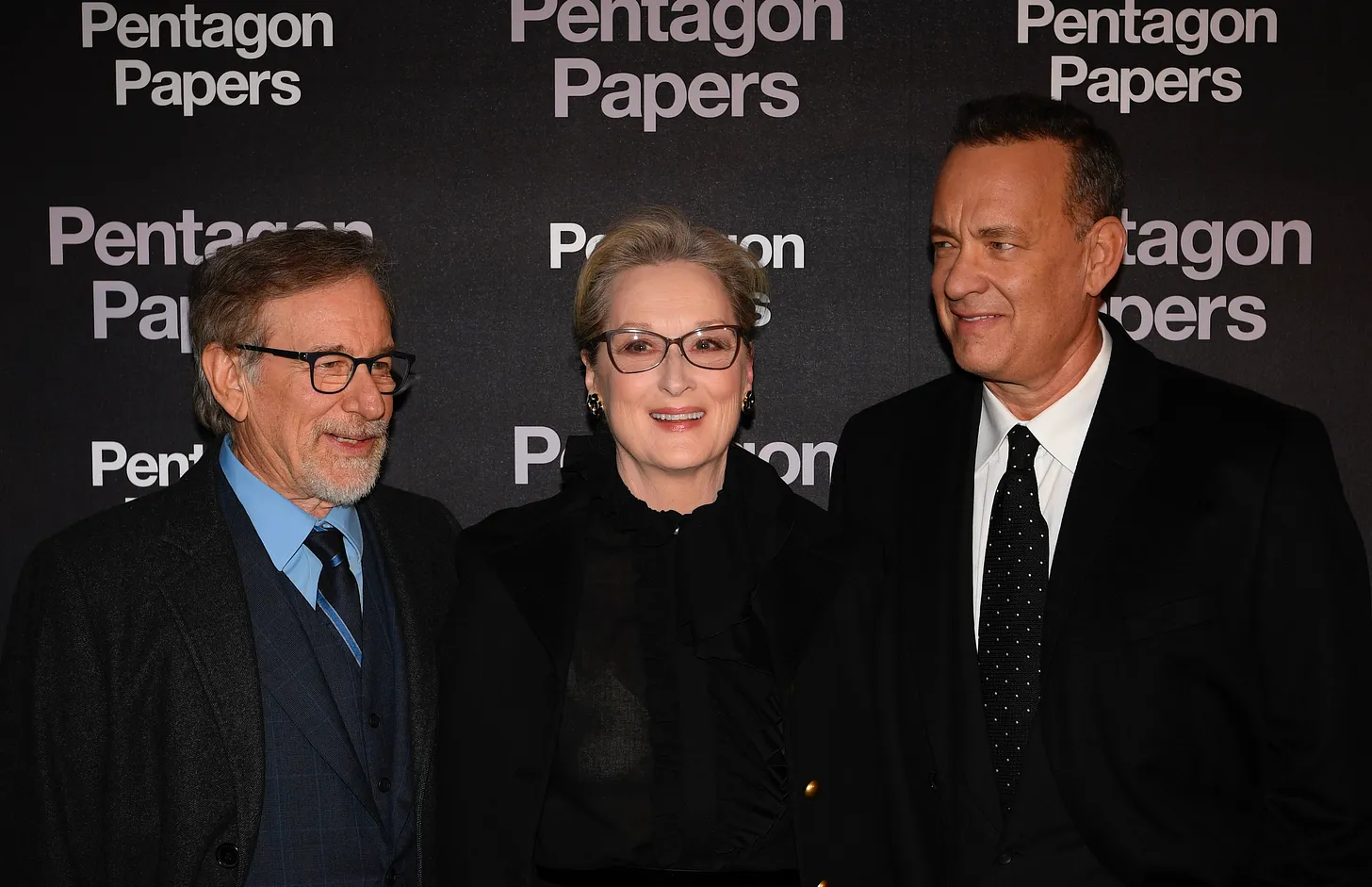

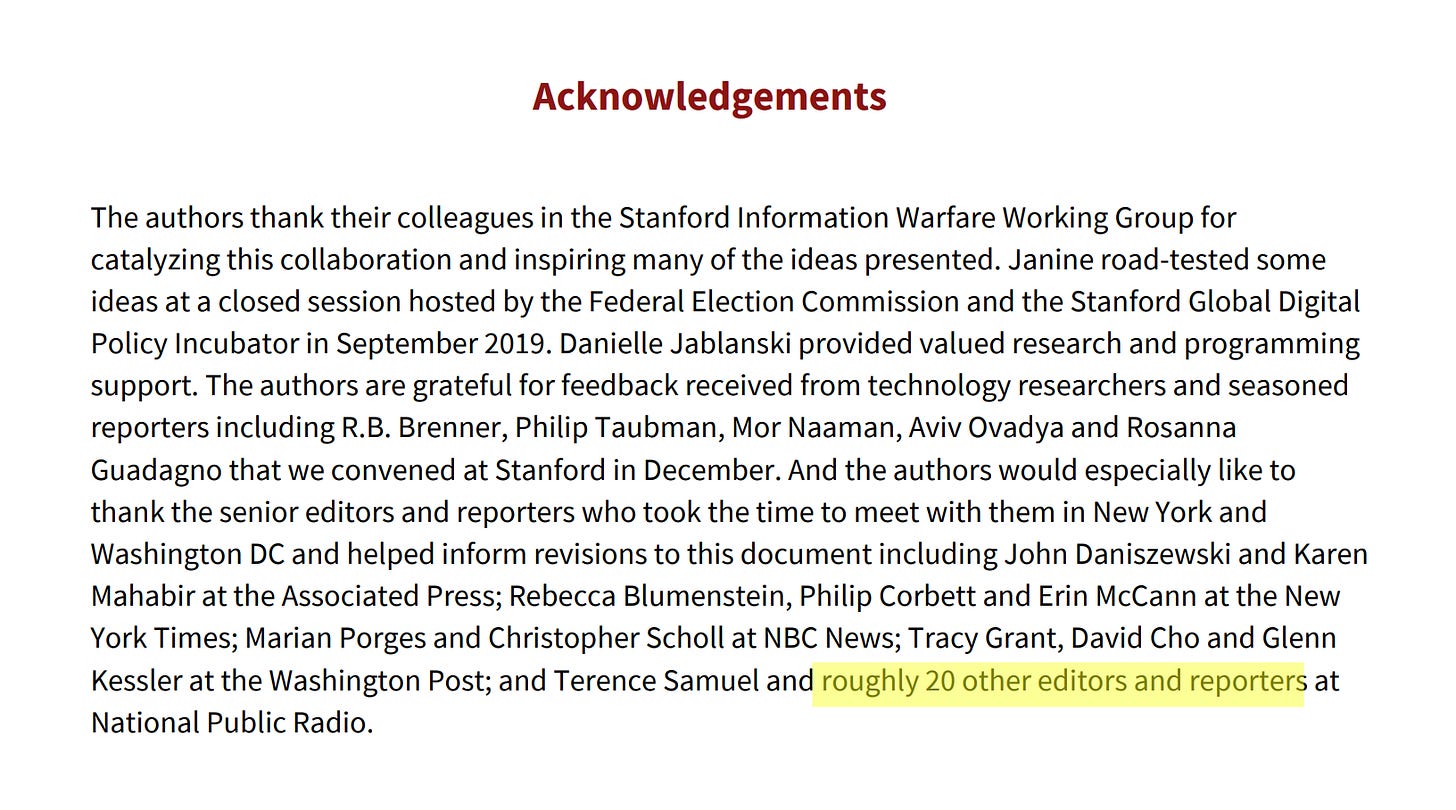

Three steps later, the two authors posited that reporters “Break the ‘Pentagon Papers Principle.’” What’s fascinating about this ambitious change proposal is who signed off on it. In addition to onetime New York Times figures like Taubman and Corbett, and current and former Washington Post representatives like R.B. Brenner (a consultant on the movie The Post, lionizing the Pentagon Papers decision!), Glenn Kessler, David Cho, and Tracy Grant, the Stanford authors cited Terence Samuel and “roughly 20” other editors and reporters at National Public Radio:

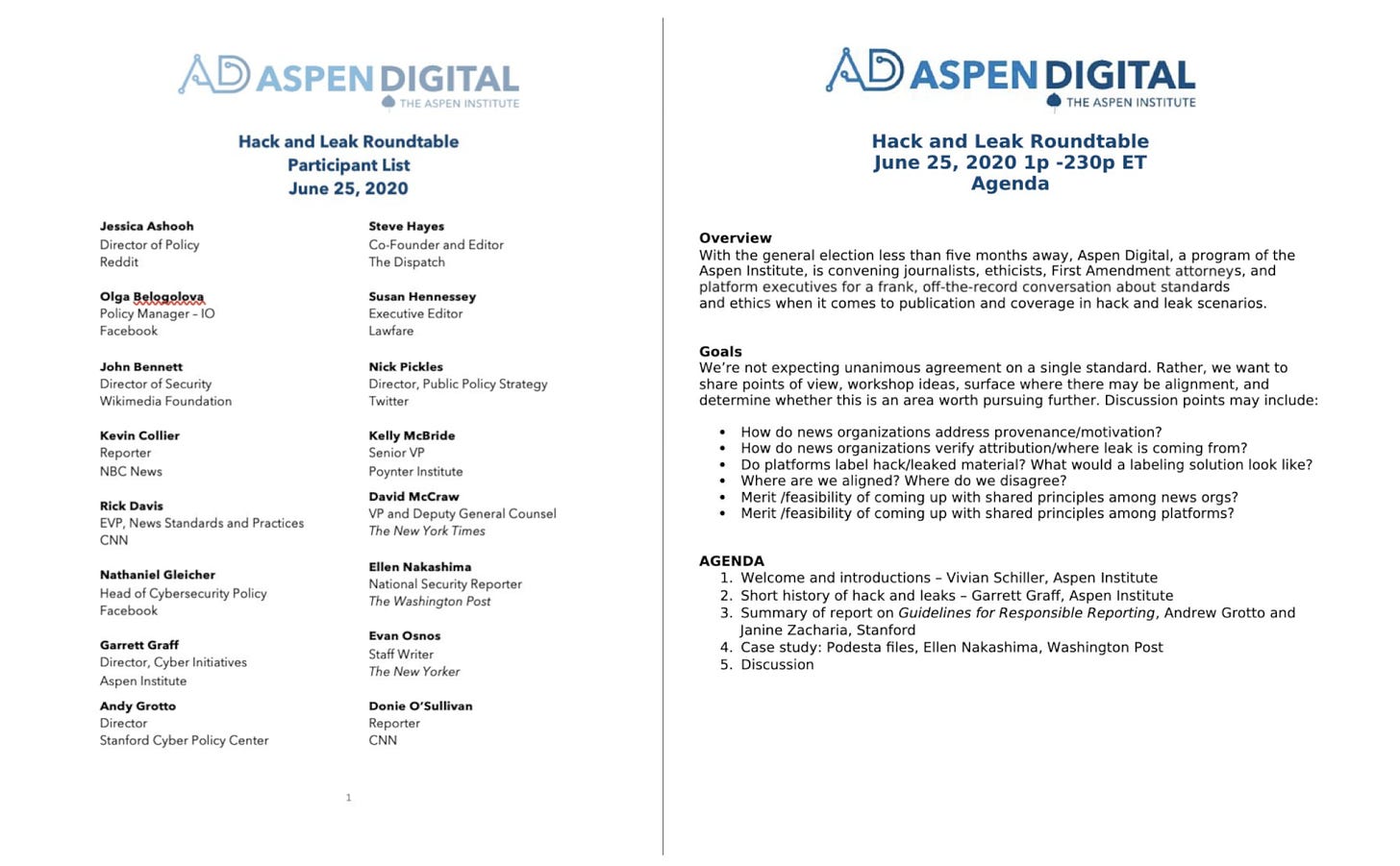

Over the summer, Zacharia and Grotto were listed as participants in the Aspen Institute’s “Hack and Leak” discussion by Zoom, which also included Google policy chief Clement Wolf, Gleicher, Sanger, Nakashima, Twitter’s Nick Pickles, NPR’s Dina Raston, Lawfare’s Susan Hennessey, Jack Stubbs of Reuters, Kevin Collier of NBC, Kelly McBride of the Poynter Institute, and many others from in and around the media business.

The Zacharia/Grotto report was presented in the discussion, and the first of the listed “goals” of the Zoom talk was “How do news organizations address provenance/motivation?” Schiller reminded attendees that “this meeting is OFF THE RECORD.”

Even before the attendees completed the remarkable “Hack-and-Dump Working Group” exercise, in other words, the group already achieved key goals. A wide representative sample of major news organizations agreed to attend a conference off the record, and did not fink on each other when a goofy covert plan for de-amplifying a “Burisma leak” damaging to the Biden campaign was delivered in a Word document by email to attendees.

This was followed by the “Partnership for a Healthy Digital Public Sphere” summary circulated by Schiller in September, which in turn was closely followed by the release of the actual New York Post story, which was of course halted by tabletop attendee companies Facebook and Twitter. After the Post piece was blocked, Roth received an email from Zacharia commenting on the “bold decision” the company took regarding the “giuliani nypost disinformation story.”

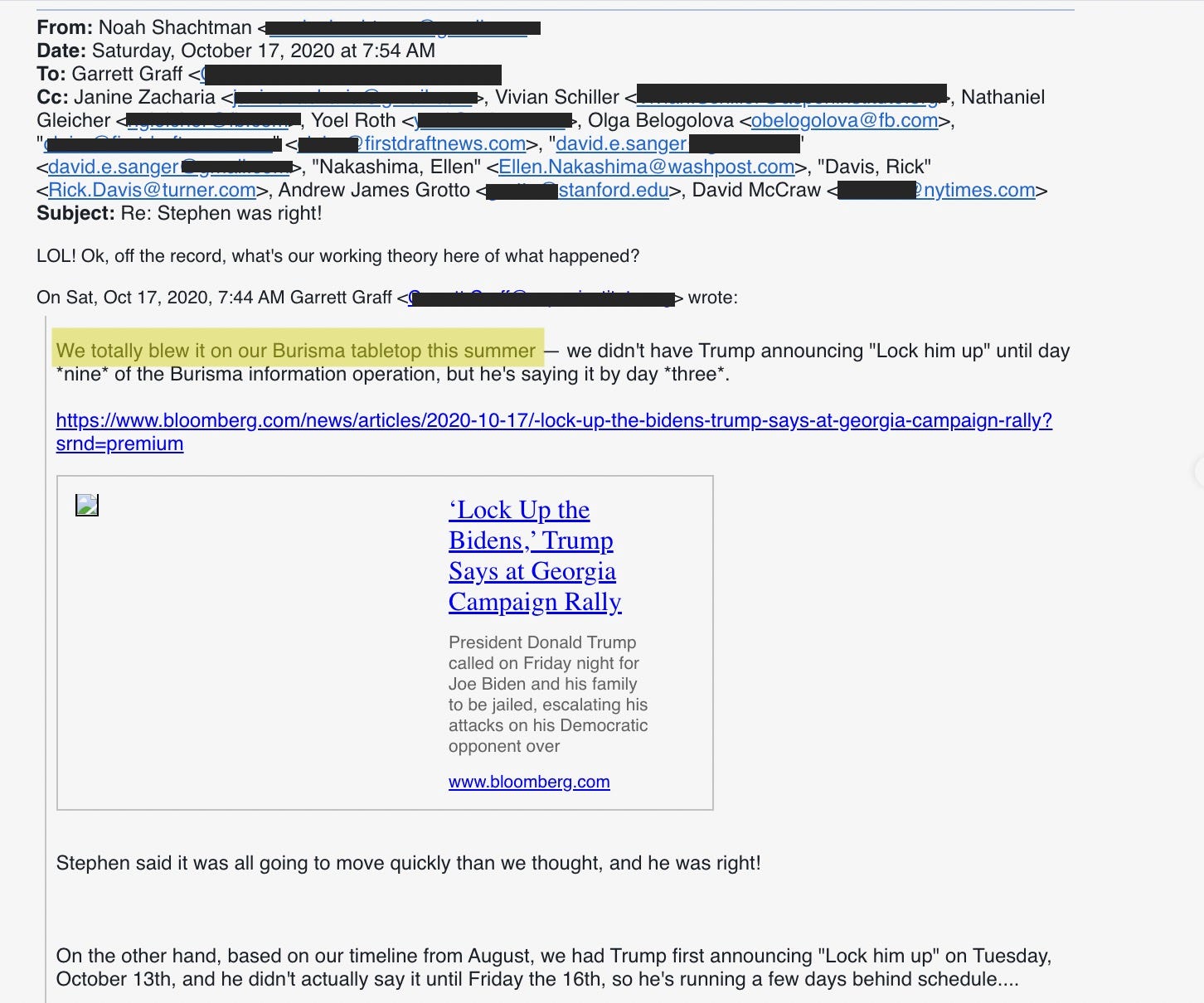

In a new #TwitterFiles thread by Racket’s Andrew Lowenthal last week, correspondence was released from some attendees of the Aspen Institute exercise who touched base after the real Post story broke. Emails showed them joking that they were off only by days in their predictions.

“We totally blew it in our Burisma tabletop this summer,” wrote Garrett Graff, a Wired contributor who also worked at Aspen Digital. “We didn’t have Trump saying ‘Lock him up!’ until day nine of the Burisma information operation, but he’s saying it by day three.” Graff linked to a Bloomberg piece on Trump’s reaction to the Post expose, and fellow attendee Schactman replied, “LOL.”

The emails included Zacharia and Grotto in the har-har chain.

For all the talk about preparing America for “disinformation,” what actually happened in the end was the cream of the American press corps agreeing to cover (or cover up) news as a cartel, jointly practicing “models of journalistic restraint” with one story. Although the Aspen seminar was mentioned in a few places in print over the course of the next years, notably in Wired by Graff on October 7th, none of the tabletop participants ever came close to describing the elaborate “exercise” in which participants engaged in a thorough walk-through training themselves how to prioritize “provenance” in a newsworthy story about Hunter Biden. Thanks in part to a tabletop-predicted statement by “former senior intelligence officials,” provenance did become the lens through which most mainstream outlets initially covered the story — erroneously however, since the story was not, as it turned out, Russian disinformation.

For nearly half a century since 1971, the Washington Post and the New York Times earned fame and praise for standing up to government attempts to suppress newsworthy information in the Pentagon Papers. In 2020, key figures from both papers openly abandoned the legacy of that episode in favor of a questionable new standard that stresses the mechanics of information suppression. How much more evidence do we need that the traditional role of media has been turned upside down?